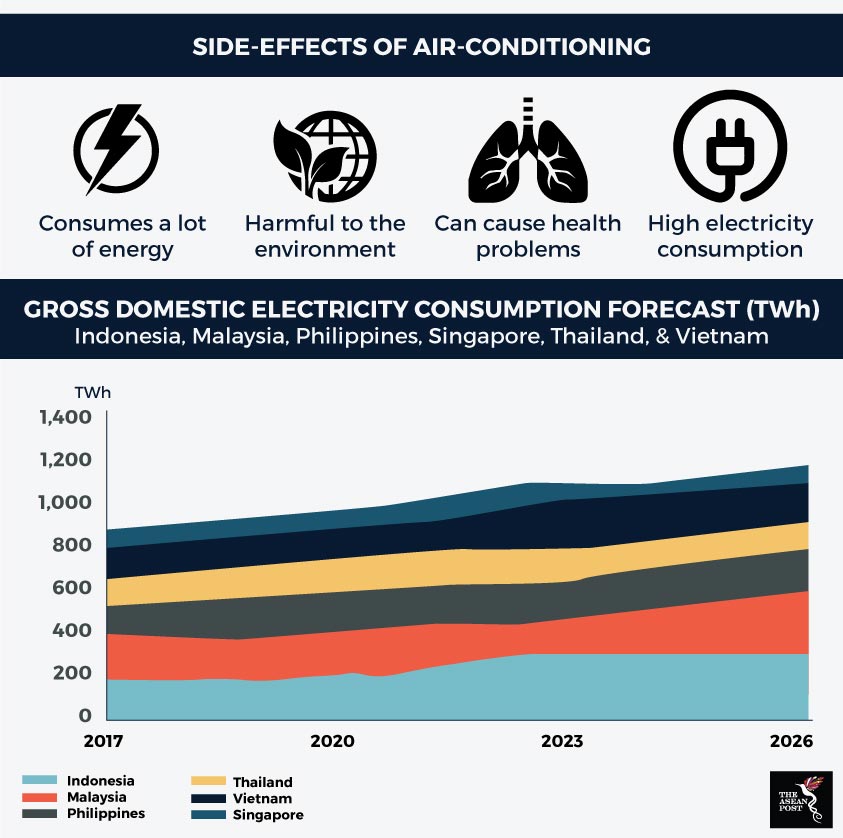

Southeast Asia’s electricity consumption has been rising at an annual rate of 7.5 percent from 155.3 terawatt hours (TWh) in 1990 to 821.1 TWh in 2013, according to a white paper by the ASEAN Centre for Energy in the Spring 2016 issue of Cornerstone Journal.

About 60 percent of electricity usage in Southeast Asian cities is attributable to the use of air-conditioning alone. The study was commenting on the correlation between higher GDP per capita and higher electricity use in six Southeast Asian countries, namely Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

At this rate, it is projected that air-conditioning could account for up to 40 percent of Southeast Asia’s electricity consumption by 2040.

Environmental cost

Findings from the white paper also reveal that 80 percent of ASEAN’s electricity is generated from fossil fuels, with Vietnam and Indonesia operating the highest amount of coal plants in the region. Higher electricity usage contributes to higher greenhouse gas emissions, which in turn results in global warming.

“Gas molecules that absorb thermal infrared radiation, and are in significant enough quantity, can force the climate system. These types of molecules are called greenhouse gases,” explained Michael Daley, an Environmental Science professor at Lasell College in the United States (US). Climate forcing refers to any variations to the climate which arise from outside the climate system itself.

Greenhouse gases can consist of carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and fluorinated gases – of these, methane is released during the production and transport of coal, whereas carbon dioxide is released when coal, natural gas and oil (fossil fuels) are burnt.

Meanwhile, fluorinated gases include hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which are synthetic greenhouse gases with 1,000-3,000 times more global warming potential than carbon dioxide. These gases currently make up about one percent of total global greenhouse emissions, but this figure is likely to increase as air-conditioning use rises around the world.

Efficient air-conditioning units

In December 2017, Eco-Business, an environmental media agency stated that demand for air-conditioning in ASEAN countries is projected to rise from 6.5 million units in 2013 to 1.6 billion in 2018.

With demand on an upward scale, increased efficiency of air-conditioning units would be key for Southeast Asian economies to control the negative impact on the environment. However, public awareness of the impact of air-conditioning on the environment remains low.

Source: BMI Research 2016

“Most Indonesians don’t understand how to operate air conditioners (ACs) and lack awareness of the importance of saving energy,” said Herbert Innah, an Electrical Engineering lecturer with the University of Cendrawasih in Jayapura, Indonesia.

“If people want to cool the room as quickly as possible, they set the temperature as low as they can. If they want to use a meeting room the next day, they turn the AC on the day before,” he explained.

Only 18.4 percent of respondents to a survey carried out by Eco-Business Research and Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program (K-CEP) were aware of the negative impact of HFCs emissions in air conditioning on the environment.

Government policy and regulation could also help increase understanding and awareness of the negative impact of air-conditioning on the environment. An example of government regulation is the introduction of a higher Energy Efficiency Ratio (EER) for all air-conditioning units produced.

EER refers to the ratio of total cooling capacity against the effective power input into the device. A higher EER indicates higher efficiency of the unit. ASEAN countries have agreed to adopt a minimum EER of 2.9 watts (W) by 2020 for all air-conditioning units produced with a capacity of less than 3.5 kilowatt (kW). This was after the ‘ASEAN Regional Policy Roadmap for Harmonisation of Energy Performance Standards for Air Conditioners’ was endorsed at the ASEAN Ministers of Energy Meeting (AMEM) in September 2015.

Improving the quality of air-conditioners by implementing new technologies could be another solution. Reducing negative effects on the environment would entail a shift from non-inverter air-conditioning to inverter air-conditioning. Imports of non-inverter air-conditioning into Indonesia would be reduced in the future, according to Farida Zed, a former director of Conservation Energy at Indonesia’s Ministry of Energy & Mineral Resources (MEMR). Inverter air-conditioning involves the installation of a compressor motor in the air-conditioning unit to ensure consistent regulation of air-conditioning temperature. This increases the efficiency of the air-conditioning unit.

The need for more efficient energy use in air-conditioning has spurred the National University of Singapore’s researchers, for one, to invent water-based air conditioning. Instead of using HFCs, the air-conditioners rely on rain water. They also use 40 percent less electricity compared to conventional air conditioning units.

If electricity consumption could be reduced by 100 TWh, it could potentially save the region electricity bills of up to US$12 billion annually.

Should Southeast Asia continue cooling down, it will need to do so on a much more efficient basis, or risk incurring ever-growing costs, to both, the economy as well as the environment. While already working towards the reduction of the impact of air-conditioning on energy consumption and the environment, ASEAN has to do more before the situation becomes unmanageable.

This article was first published by The ASEAN Post on 30 January 2018 and has been updated to reflect the latest data.

Related articles:

Global warming and pollution giving birth to ‘dead zones’

Making Southeast Asia energy efficient