As ambitious declarations go – even for Boris Johnson – it was a big one. At the weekend, the United Kingdom (UK) prime minister said he would urge the G7 leaders to vaccinate the world against COVID by the end of 2022.

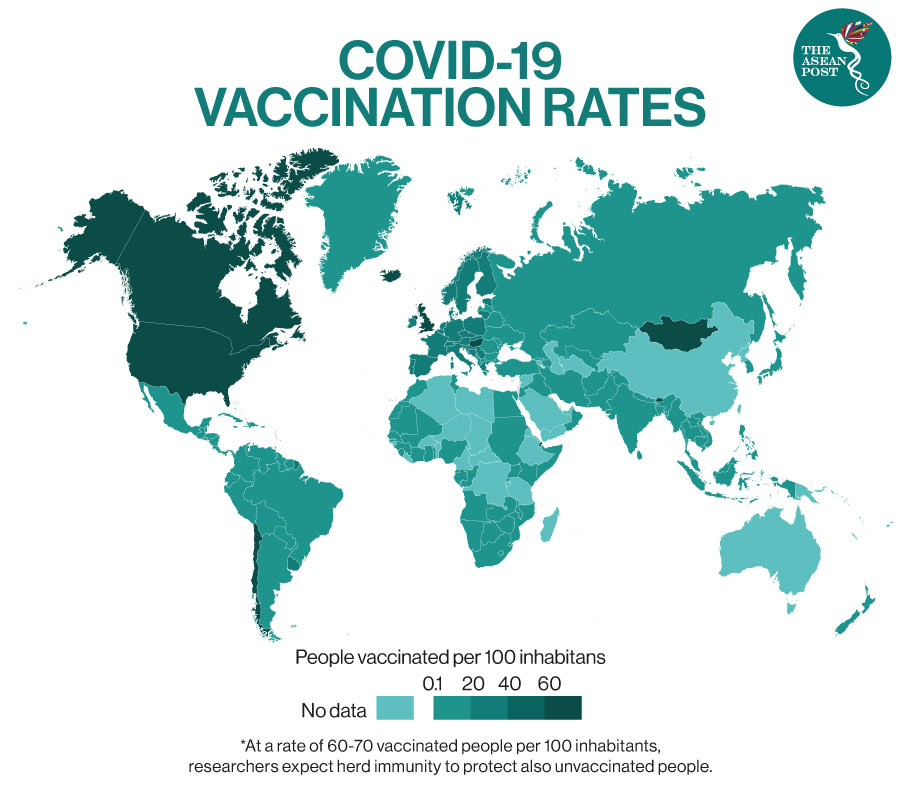

But is this feasible? That rather depends on your definition. No country will vaccinate every adult. Vaccinating enough to achieve herd immunity, which could be 60 percent or 70 percent, is the real aim. It is possible to achieve that by December 2022, say experts, but only if the G7 leading economies move immediately to make it happen.

The COVAX scheme under the United Nations (UN) umbrella should have been the route to vaccination for low-income countries. It was designed as their lifeline. COVAX signed contracts with manufacturers to buy two billion doses by the end of this year.

But it is stymied. Its main supplier is the Serum Institute of India (SII), which is now churning out vaccines in response to the terrible surge in domestic cases and deaths and will not be able to fulfil its contracts to COVAX or individual countries before the end of the year.

Dr Bruce Aylward, senior adviser to the director general of the World Health Organization (WHO), who is heavily involved in the vaccine efforts, said: “This is where the UK becomes really important and the G7, because right now we’ve got this gap of death. In June, July, August, September, there’s no vaccine out there for love nor money, in terms of being able to procure it.”

The answer is donations. Big promises have been made. The UK has bought enough vaccine to immunise its entire population several times over – more than 500 million doses of eight different vaccines. The government has promised to donate the surplus to COVAX.

But it’s no good doing that in December, say experts – it needs to happen immediately. People are dying now. There is a big coronavirus surge in Nepal as well as India, and concern about rising case numbers in Africa, where accurate counts are not always possible.

By autumn, there should be more vaccine production and supplies will reach low-income countries. If donations start to arrive as well, those countries will not be able to use them all – they have too few clinics and refrigeration facilities and too few healthcare workers to give the shots. Vaccines will expire.

Steady Supply

Aylward said countries needed to be given a steady supply so that they could set up systems that worked, and that would require training a workforce and money. On Monday, 230 former world leaders from five continents wrote to the G7, adding their voices to the call for the strongest economies to foot two-thirds of the bill for vaccines, which is estimated at US$66 billion over two years. Save the Children published polling that suggested most people in five richer countries, including the US and UK, supported that.

Aylward said it made financial sense. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its recent plan for ending the pandemic set a target of vaccinating 40 percent of the population of every country by the end of this year and 60 percent by the middle of 2022.

“Everybody thinks about this in terms of a health security issue and a life-saving issue, but the IMF came at it from an economic perspective. They said: ‘Look, there’s US$9 trillion that you will add to the global economy by doing this by the middle of next year and those gains will run out through 2025.’ When they looked at it from an economic perspective, it was just staggering.”

So far, 75 percent of the world’s COVID-19 vaccines have been distributed in just 10 countries.

Romilly Greenhill, the UK director of the international non-profit One, said the target to vaccinate the world might look ambitious, but was necessary. “We’re not going to end this pandemic anywhere until we end it everywhere, so actually we do need to be aiming at sort of global herd immunity – 70 percent coverage – kind of levels, by the end of next year.

“Otherwise, the risk is that we’re going to end up with variants and we’ve already seen a number of variants from around the world. So, you know it is very ambitious, but actually there’s no other option, and so we need the G7 to really step up to the plate and commit to the plan, to the resources, that are needed to achieve that.”

She said it would “need to be a kind of superhuman effort”, but it was possible. She pointed to the HIV/Aids pandemic: there is still no vaccine, but donor countries have funded the mass distribution of antiretroviral drugs in clinics across low-income countries.

“It’s not perfect. We have a long way to go. But we have learned that if you have a really coordinated approach, if you have big organisations like the Global Fund or GAVI (the global vaccines alliance which is now jointly running COVAX) or who are working together with governments, you can achieve enormous progress. I think it’s something like 2.1 million lives saved from HIV/Aids just from UK contributions alone, so it’s quite significant.”

Financing Crucial

Liam Sollis, head of policy on UNICEF UK’s national committee, said equitable distribution of vaccines, involving dose-sharing, was the first priority. “Then the second bit is about scaling up manufacturing to ensure that we’ve got enough supply available to meet all of these targets around vaccinating the world,” he said.

“To do that, number one, the financing has to be in place, and the commitments that we’ve got have all been generous, and they’ve covered the needs, up to where we’ve got to this year. But there’s still not money available for the rollout through 2022 and the scale of ambition really needs to increase.”

There are far too few manufacturing facilities around the world, especially in low-income areas. AstraZeneca, which aims to be the main global low-cost vaccine, has contracted with more than 20 of the more established vaccine factories in the world, including Mexico, Indonesia and China, as well as the SII. But there aren’t many others.

For the sake of saving lives now and in the future, many believe vaccine manufacturing has to increase worldwide. An annual five billion doses of vaccine were being produced for the routine immunisation of children against killer diseases such as measles and diphtheria before the pandemic.

About 15 billion doses of COVID vaccine are needed. And it can only be done if the technology, knowhow and skills to make vaccines are shared by the big pharmaceutical manufacturers with enterprises in Africa and Asia. – The Guardian