ASEAN’s exponential economic growth and social mobility is a double-edged sword. The region’s growing strategic relevance makes it a prime crosshair for cyberattacks, with the rise of intangible threats now becoming more prevalent within the region. Cybersecurity threats are pervasive and create problems in various sectors. The financial and energy sectors are prime examples of industries that have been affected in the recent past by the insidious hands of cybercriminals.

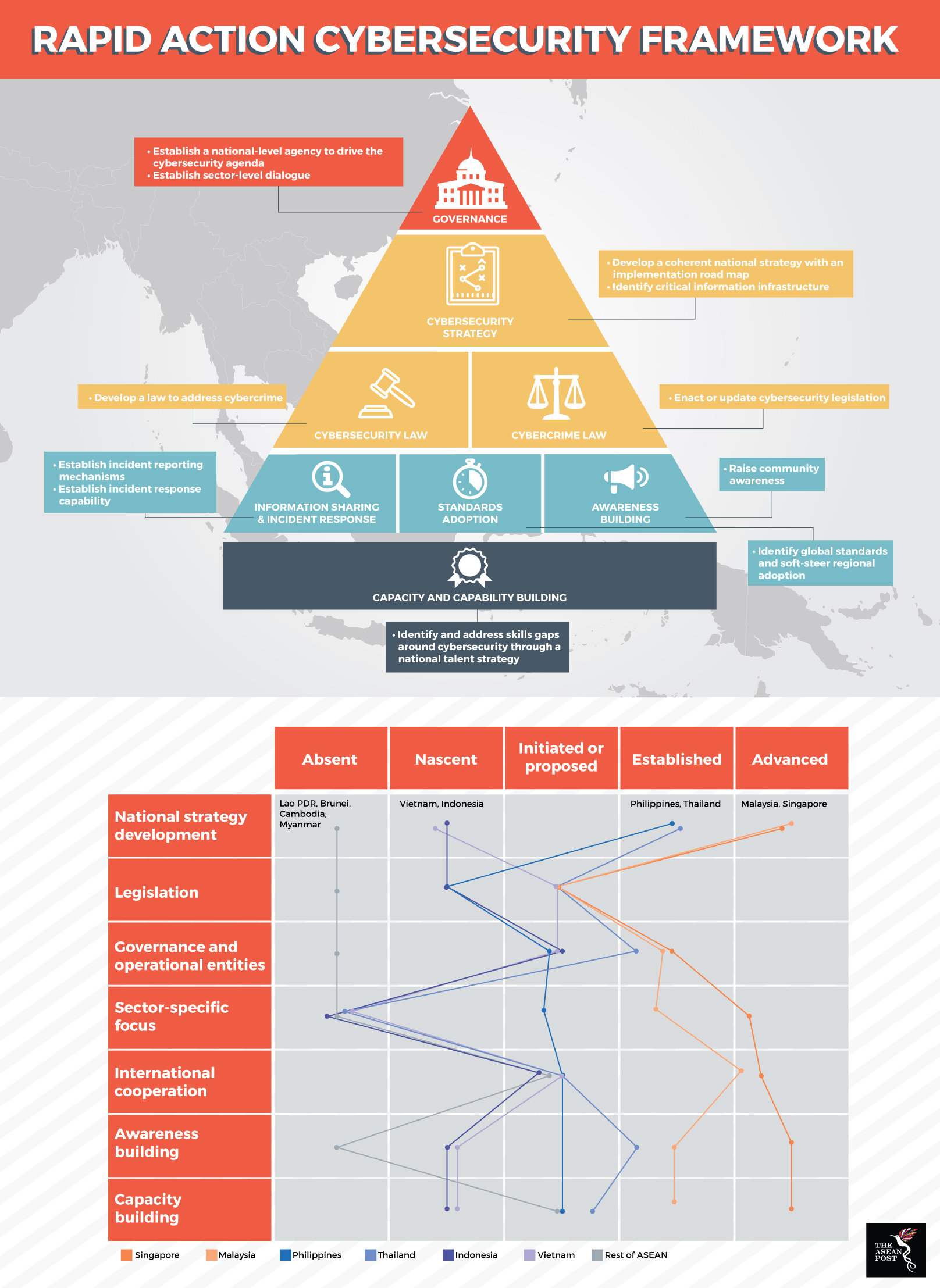

There is no doubt that cybercriminals are attracted to ASEAN’s economic growth and prosperity. A growing awareness to defend its cyberspace and ICT infrastructure has necessitated collaborative efforts by ASEAN member states. Four ASEAN mechanisms are in place to investigate aspects of cybersecurity and cybercrime, which are; the ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Transnational Crime (AMMTC), ASEAN Telecommunications and IT Ministers Meeting (TELMIN), the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), and the ASEAN Senior Officials Meeting on Transnational Crime (SOMTC).

The ARF’s initiatives include ASEAN seminars on cyber-terrorism, conferences on Internet use, and workshops on cyber incident response as well as preparedness measures to enhance cybersecurity. The island Republic of Singapore has even created a US$10 million ASEAN Cyber Capacity Fund, which when applied, will improve cybersecurity capabilities in the region.

The financial impact of cyberattacks is devastating. According to the Asia Pacific Risk Centre, the global cost of data breaches is projected to reach US$2.1 trillion by 2019. Such a repercussion should be a wake-up call for governments in the region to bolster their defences in the digital realm.

Source: T.S. Kearney

Financial implications

Based on a report by The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington, Malaysia lost approximately US$900 million to cybercriminals between 2007 and 2012, with an average of 30 individuals falling prey to cybercrime every day. It is important to note that these figures keep rising yearly. Furthermore, 70 percent of crimes in that country fall under the category of cybercrime. In Indonesia, cybercrime costs the government there US$2.7 billion annually. As of 2013, Singapore had the highest per capita losses to cybercrime globally at US$1,158.

Even with all these measures in place, it is tough to stay one step ahead of cybercriminals. It seems to be the case that these miscreants are always prepared. The danger of an attack is always imminent, like a black cloud over the region, which creates uncertainty within governments as to whether they would be attacked next. A cyberattack would have serious, far-reaching consequences. Financial institutions, defence centres, central banks, hospitals, and airports are some of the locations that could suffer from such an attack.

Piracy is also a substantial threat to regional cybersecurity, as pirated software often lacks the traditional security mechanisms of licenced programmes. This lack of security could contribute to the spread of malware. Such a fact is disconcerting as Cambodia has a piracy rate of over 95 percent. Vietnam and Indonesia follow with piracy rates of over 80 percent. At this moment, it is projected that regional consumers will spend US$10.8 million dealing with malware issues related to pirated programs.

Regional defence sectors are also at risk of cyberattacks. According to the Asia Pacific Risk Centre, the personal data of 850 individuals was stolen from the online database portal of Singapore’s Defence Ministry in 2017.

The energy sector has not been spared too. Currently, there is no large-scale deployment of smart grids in the region. However, it is not implied that traditional power grid systems are safe from cybersecurity threats. The highly computerised nature of operations in power distribution centres can be affected by invisible hands. Interconnected computers and networked devices within these centres are exposed to the aforementioned concerns.

Physical damage and system malfunctions to power generation stations and substations can occur during a cyberattack, leading to power disruptions and even blackouts. In 2015, the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv fell victim to such a scenario as more than 225,000 consumers were affected by blackouts caused by cybercriminals. Such a situation should be taken as an example of the multifaceted nature of cyberattacks.

As such, regional initiatives are critical towards limiting cybersecurity vulnerabilities among ASEAN member states. Good governance and clear policies at the national level should reinforce the regional outlook on dealing with this threat. It is imperative that ASEAN member states promote public-private partnerships, considering the many essential services provided by the private sector. Monitoring systems should also be consistently updated. Until all this is put in place, chances are, any country in Southeast Asia could be the next target of cybercriminals.