Cambodia has witnessed strong growth in terms of its internet penetration rates. In July, Telecommunication Regulator Cambodia spokesperson Im Vutha said the total number of internet users as of the end of June had reached 12 million, up from 10.8 million in December. The number pushes the Kingdom closer to its 2020 goal where the government expects that 100 percent of the urban dwellers and 80 percent of rural dwellers will have access to the internet. But there are two sides of the internet coin to look at in Cambodia.

While the country seems to be heading in the right direction as far as providing internet access to its people goes, the country has also become notorious for its dwindling internet freedom especially in the face of Cambodia’s recent 2018 election.

United States (US)-based Freedom House’s 2017 report noted that internet freedom deteriorated in Cambodia that year, with prison sentences and new arrests for online speech and technical attacks on activists and journalists.

“Criminal charges in relation to Facebook posts, relatively uncommon just two years ago, appear to be increasing in advance of 2018 elections and were used to punish the political opposition. The opposition had made gains in the 2013 elections following their embrace of digital tools, though they failed to unseat long-serving Prime Minister Hun Sen. Lengthy sentences passed during the reporting period signalled a shrinking space for online speech,” the report stated.

Local studies have not painted a bright picture of the situation either. The Cambodia Center for Independent Media stated in its 2017 report that seven Facebook users were either arrested or sought by authorities for sharing information and opinions on the social media platform.

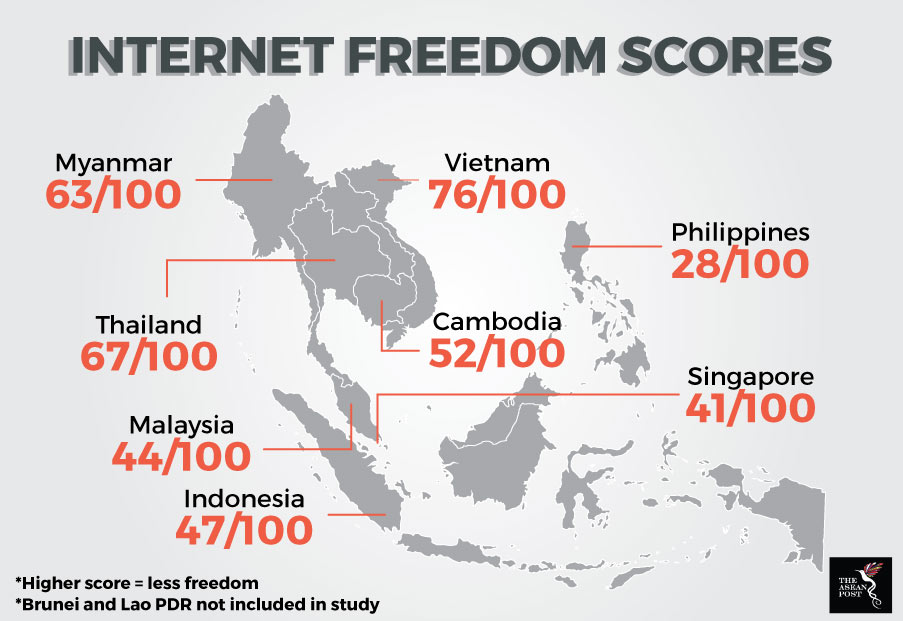

According to Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net 2017 scores, Cambodia’s freedom score was at 52 out of 100 with a lower score showing a higher freedom rating. While this only places Cambodia somewhere in the lower middle half compared to other ASEAN countries, Freedom House noted that infringements of internet freedom were only offset because of the increased internet penetration rate.

Another important factor to note is that Cambodia has seen a steady decline in internet freedom based on its Freedom on the Net scores. In 2014, it scored 47 out of 100 and the following year it dropped one point to 48 out of 100.

Source: Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net 2017

It’s not over yet

Soon after 2018 was ushered in, the Cambodian government drafted a new cybercrime law to protect both, buyers and sellers online from the threat of cyberattacks. This new law aims to implement anti-cybercrime measures by establishing the National Anti-Cybercrime Committee (NACC) that will be chaired by Prime Minister Hun Sen himself. The upcoming law, however, has been seen as just another attempt at stifling free speech on the internet.

Part of the reason for the concern is the huge scope of powers that the NACC wields under the new law. Its duties include, among others, advising and recommending courses of action to the operational arm - the General Secretariat -, supervising implementation and workflow of the General Secretariat’s action plans, and performing any other duties as may be directed by the Cambodian government. This last duty especially coupled with the fact that the NACC chairman is the Prime Minister shows a clear conflict of interest as far as implementing the law goes.

The government’s response, however, is to deny that there has been any crackdown on internet freedom. In June, when announcing that it will now monitor social media and online publishing platforms operating on its internet networks in an attempt to stop the spread of falsehoods, Ministry of Information spokesperson Ouk Kimseng told local media that “this will benefit the public and help stop the sharing of ‘provocative information’ that can cause social chaos.”

If Cambodia is serious about combatting cybercrime and not infringing on its people’s internet freedom then one point it can look at is ensuring that the NACC remains objective and independent. This could perhaps be done by making the committee either bipartisan or non-partisan and reconsidering the appointment of the Prime Minister as its chairman.

Related articles:

Growing concerns for Internet freedom in Southeast Asia