Despite the huge potential of renewables in Southeast Asia, the lack of bankable solar projects remains a key barrier to increasing solar development in the region. Bankability refers to the financial viability of renewables projects, i.e., whether lenders and investors are willing to extend financing to any one project.

The lack of bankable renewable energy projects can be attributed in part to poorly drafted power purchase agreements or PPAs. A case in point was Vietnam’s draft solar PPA, which was criticised by international law firm Mayer Brown JSM in a 2017 opinion article as “inadequate” because of sparse provision for various stipulated matters.

PPAs are usually entered into by a state-owned utility (purchaser) and private utilities company (power producer) of which a third party, who is usually the investor, also becomes privy. Once the plant has been built, the PPA further regulates the sale of electricity back to the purchaser, setting out terms that define the purchaser’s obligation to pay the power producer tariff payments.

PPAs are used to secure payment streams for projects where projected revenues are uncertain from the outset and competition from a cheaper, domestic supplier is likely to undermine the long-term profitability of the project.

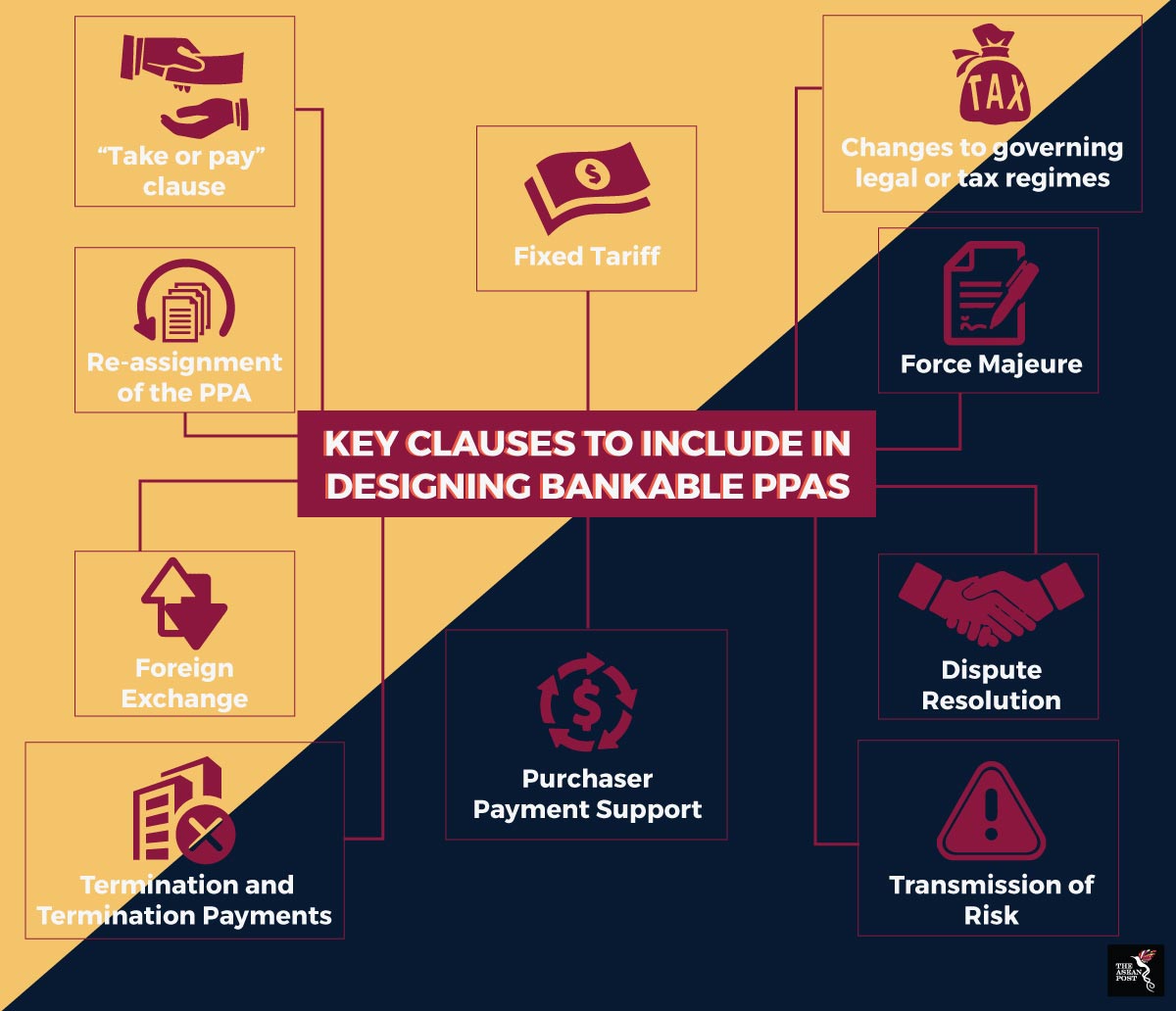

In general, a bankable PPA would include provisions for a sound payment mechanism, fixed tariff rates and for the rates to be subject to foreign exchange conversion when applicable.

Although a standard PPA format would be sufficient for smaller power projects, a more detailed PPA is needed for larger-scale projects, in order to cater to a wider range of eventualities.

According to Mayer Brown, Vietnam’s draft solar PPA also did not impose any ‘take or pay’ provisions on the purchaser. According to financial education website, Investopedia, a take or pay provision is one that requires a purchaser to take a stipulated supply of goods or services from the supplier by a certain date, failing which they would have to pay the supplier a fine.

This meant that the PPA did not adequately protect the financier from risk in the event that the purchaser was unable to receive power, for instance, should there be a breakdown in the electricity grid.

Source: Overseas Private Investment Corporation

Baker Mackenzie, too further pointed out that the draft solar PPA failed to provide for an outstanding debts settlement mechanism with regard to a private investor’s liabilities should the purchaser, Vietnam Electricity Corporation (EVN) chose to exit a solar financing deal earlier.

Even though force majeure provisions were in place, there was also a need to assign the risk caused by politics-related force majeure events to be undertaken by the state, since the purchaser was affiliated with the government.

According to Black’s Law Dictionary, a force majeure event which triggers the operation of the clause is defined as “an event or effect that can be neither anticipated nor controlled.”

Further, Vietnam’s draft PPA could also include ‘step-in’ rights for lenders in the occasion of a material default.

“Although the direct parties to the PPA are the power producer and the purchaser, this document is equally relevant to lenders and equity investors of the energy project,” writes Arvin Holkoree, a barrister from Juristconsult Chambers in an opinion piece for the online professional resource site, Mondaq.

“They would want the project to be creditworthy and may further want to restrict the ability to assign or transfer the PPA,” he continued.

Even with lenders’ step-in rights, additional provision can also be made for the project to be transferred by the purchaser to a new owner in case of a material breach. This adds another layer to the protection of financiers’ rights.

Later amendments to the draft solar PPA did not incorporate many of these proposed amendments, the energy publication, PV Tech reported in late 2017. The sole significant change, according to Gavin Smith pertained to a new provision for a Vietnam Dong-United States Dollar currency conversion.

That’s not to say that there are no bankable PPAs in the region thus far. The only issue is that so far, there is a lack of standardised PPAs, resulting in hit and misses when it comes to renewable energy project bankability. Most PPA awards are negotiated and awarded on a case-by-case basis, the 2018 ‘Renewable Energy Market Analysis - Southeast Asia’ report by IRENA stated.

Although efforts by the Vietnamese government to create boilerplate PPAs is in itself commendable, such efforts need to be supplemented by greater research initiatives and better risk calculations, among other factors. The political will to commit to such efforts could be a start.