In a world with warmer atmospheric temperature, the already observed changes to the climate are expected to further worsen, resulting in increasingly more frequent and intense weather events. For vulnerable Southeast Asians living in disaster-prone conditions, climate-related events will not only continue to dominate the risk landscape, but also threaten to undo their hard-earned economic development.

For the Vietnamese city of Da Nang, its location along the central coastline of the country makes it a suitable hub for transportation, services, and tourism. However, because of the area’s low-lying topographical feature, the location also exposes its people to damaging flooding and storms. For Da Nang’s urban poor, destruction caused by these weather events on their poorly constructed and maintained homes often leave families struggling to recover.

In the effort to reduce vulnerabilities and to increase resilience of these disaster-prone communities, the government has embarked on a resilient housing project. To make this objective accessible to the urban poor, revolving loans to pay for reconstruction or modification of resilient homes were made available through the Women’s Union in Da Nang. The effectiveness test of such an effort came in 2013 when Typhoon Nari made landfall in the coastal area. Around 4,000 homes were flattened by the typhoon. However, all 245 homes built under the resilience building project survived unscathed.

Da Nang, through its Climate Change Coordination Office, also uses data to assess the climate risk for its territories, the outcome of which informed its urban planning and shaped its resilience strategies. These strategies include innovative solutions for early flood warning systems, as well as affected area and water level projection. The agency is also working with global insurance company, Swiss Re, to develop an open data-driven flood risk map to increase community awareness on disasters and disaster-prone areas.

Low-cost solution for resilient communities

Despite high mobile phone penetration, as well as robust and widespread network coverage, a mobile-based early warning system for flooding does not work well in Cambodia. The trouble with existing early warning systems was highlighted by the 2013 floods in Cambodia, which covered almost half the country, killing more than 50 and affecting nearly 1.7 million people. According to the BBC Media Trust, more than a third of the people received no warning and for three-quarters of those who did receive it, the warning came too late – during or after the flooding event.

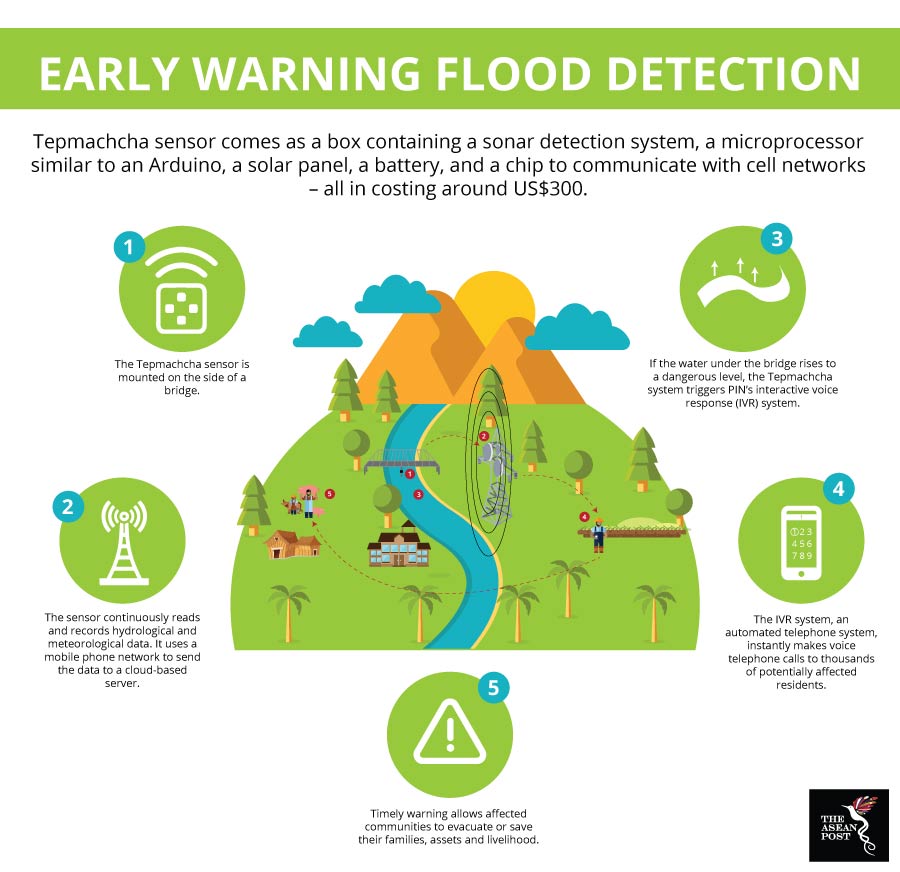

A collaboration between the American DAI Maker Lab and Czech-based NGO People in Need (PIN) resulted in an open source early warning flood detection project called Tepmachcha – the Khmer name for the fish avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu that warns mankind of catastrophic flooding. According to its co-developer, Robert Ryan-Silva, Tepmachcha was designed specifically to cater to Cambodia’s high illiteracy rate (22.8 percent in 2016) and limited support for Khmer characters on cheaper, more popular mobile phones.

“The end product is a box containing a sonar detection system, a microprocessor similar to an Arduino - a solar panel, a battery, and a chip to communicate with cell networks – all costing around just US$300. Mounted on the side of a bridge, Tepmachcha senses the water level and uses the mobile phone network to send data to a cloud-based server. Should the water reach a dangerous level, the Tepmachcha system will trigger PIN’s interactive voice response (IVR) system – an automated telephone system – to make a voice telephone call to thousands of affected residents within a matter of minutes,” he explained.

Sources: Various sources.

Two pilot Tepmachcha sensors are currently in operation and another 15 are expected to be deployed by the end of the year. These devices are built by Bespokh, a local Cambodian company which is also working on improving their hardware and software. The opt-in system currently has about 72,000 subscribers.

Access to climate related data, open data maps and bespoke solutions have helped local communities prevent weather events from developing into full-blown disasters. In both cases, high participation of local communities for input and talent allows them to contribute and be part of the solution. For other areas in Southeast Asia which are similarly exposed and prone to disasters, these initiatives should serve as an example.

Related articles:

Climate-driven hunger on the rise