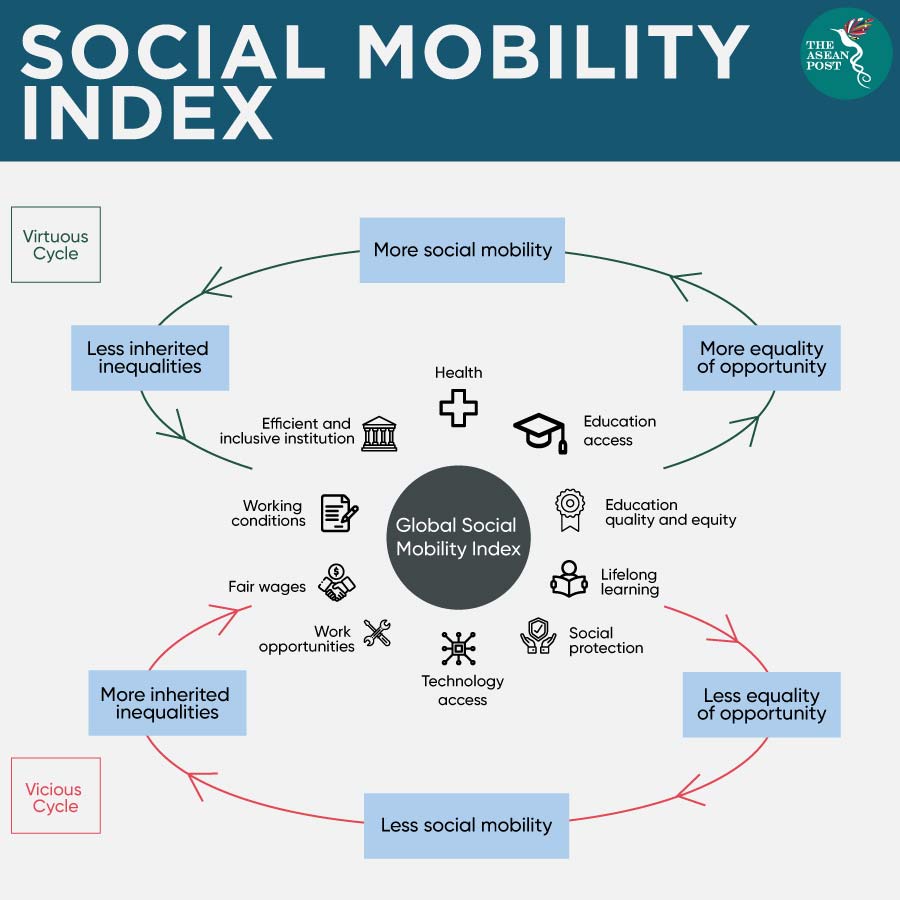

The World Economic Forum (WEF) has released its Global Social Mobility Index 2020. Social mobility entails the “upward” or “downward” movement of an individual in relation to those of their parents.

Essentially, it evaluates a child’s ability to experience a better life than their parents, while relative social mobility examines how an individual’s socio-economic circumstance inherited at birth has affected their outcome in life.

The report assessed 82 global economies against five key dimensions over 10 pillars. The index identifies the best-performing economies globally when it comes to creating equally shared opportunities, regardless of socio-economic background, gender, origin and other factors. It is also meant to be used as a tool for policymakers to improve the driving factors for social mobility and explore the different segments that contribute to it.

One of the major issues found across all 82 economies is that the right conditions to foster social mobility is lacking, while income inequality has become entrenched into respective systems.

Seven ASEAN countries were featured in the index, in which Singapore ranked highest in 20th spot on the global scale. The second-best performing ASEAN country was Malaysia at 43rd. Other ASEAN countries in the index were Vietnam (50th) Thailand (55th), the Philippines (61st), Indonesia (67th) and Lao (72nd).

All seven countries scored very high in terms of 'Technology Access' and 'Work Opportunity', similarly, they performed worst in 'Fair Wage Distribution' and 'Social Protection'.

Although Singapore ranks way above the average for all ASEAN countries in other pillars, when it comes to the two worst performing pillars, they are at par – scoring even lower than Malaysia and only slightly higher than Vietnam in Social Protection. The report estimates that improving its overall index score by even 10 points would add 4.41 percent to Singapore’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth by 2030. This could translate to an additional US$2.4 billion towards the island state’s GDP annually.

Inequality of income and opportunity

Globalisation has undoubtedly raised living standards, yet the Fourth Industrial Revolution has exposed severe inequalities across the world.

The trio of evolving economies, technological forces, and recent policy choices have deterred the progress of inclusivity of dynamic economies and societies. It was found that social conditions inherited at birth (location of birth, socio-economic status, etc.) determine an individual's outcome in life, which means that many countries have failed to reduce historic inequalities, instead reproduce it – especially in developing regions like Southeast Asia.

On the other hand, economic dynamics of digital platforms, big data and automation promote market concentration and ‘winner-takes-all’ markets. Those who benefit the most from these changes are the owners of technology or intellectual or physical capital – innovators, investors and shareholders. This has contributed to the rising wealth and income gap between those who depend on their labour and those who own capital.

Moreover, the bottom 50 percent of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries are experiencing extremely slow growth in wages, which could also be attributed to the stagnation that occurred between 2008 and 2015. While the top one percent have seen a 43 percent increase in annual income since 2009, the bottom 90 percent have seen less than a seven percent increase.

The poor performance of ASEAN countries in ‘Fair Wage Distribution’ is mostly attributed to a large number of incidents in which workers are underpaid. Additionally, in order for education to enable social mobility, it must have a direct relation to the labour market. There is also discrepancy between available skills and available jobs.

Workers with middle- and low-skilled labour are especially vulnerable to technological automation, and without the provision of continued learning, they could be left further behind in the coming digital era.

Thus, the growing digital economy in Southeast Asia is in dire need of policy reforms that accommodate changing work relationships and support job transitions without sacrificing worker rights.

It was noted that some of the worst performing ASEAN countries have adopted policies that do not reflect long-term conditions which would allow every child, young person and adult to believe in the prospect of a better future.

Related articles: