The newly-built Xayaburi dam has raised some key concerns about Lao PDR’s hydropower strategy.

While hydropower is one of the country’s main exports, Lao PDR still has to import electricity. And although the government says the Xayaburi dam will improve access to electricity for its citizens, nearly all of the power it produces will be sold to Thailand.

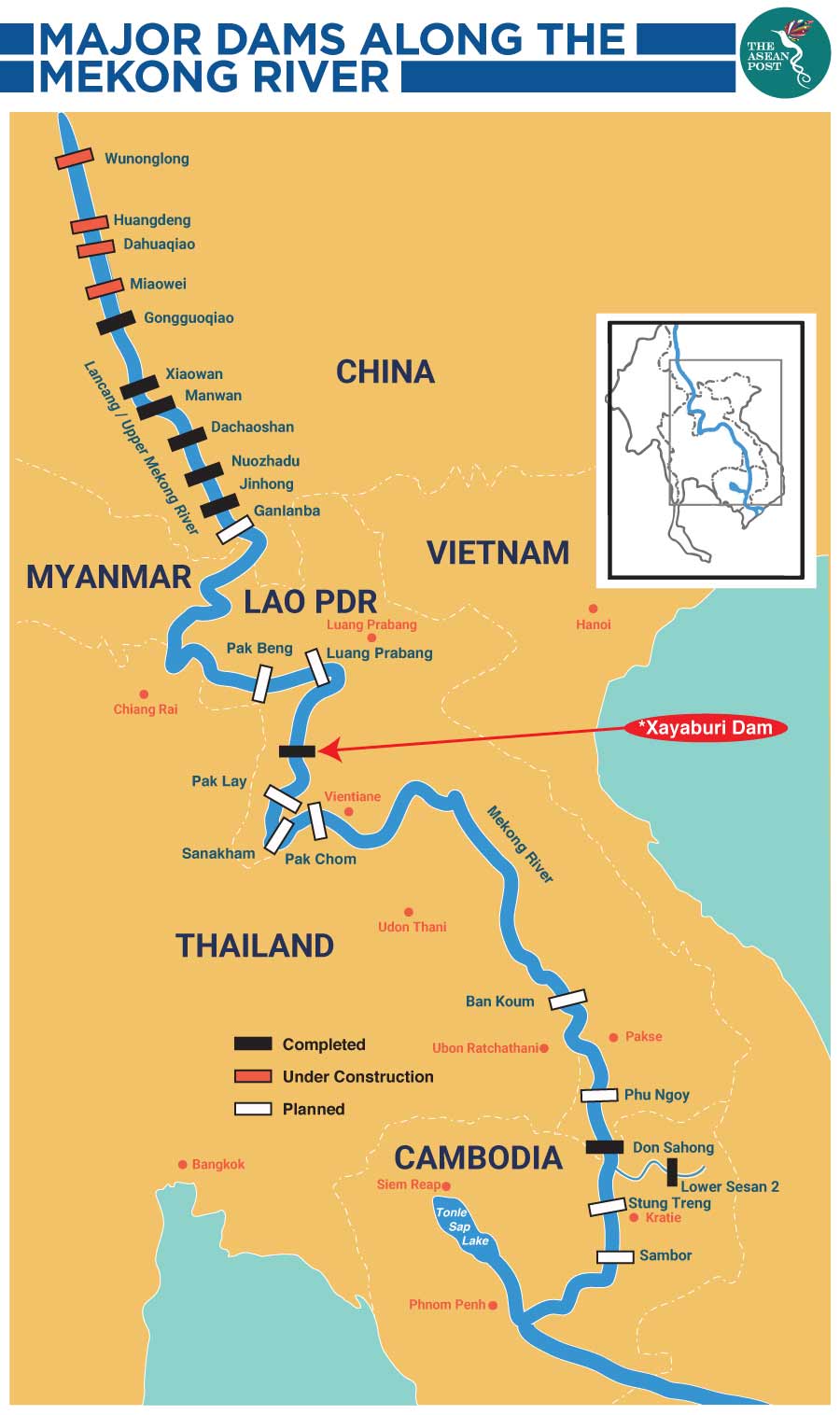

12 years in the making, the US$4.47 billion dam is the first on the lower Mekong basin and formally began operations on Tuesday despite warnings of irreversible environmental damage and imminent socio-economic risks.

The dam in the northern Xayaburi province has been plagued by controversy from the start due to unaddressed concerns about its impact on the millions of people who depend on the Mekong for their livelihoods – including the Thai, Vietnamese and Cambodian communities living downstream from the 1,285 megawatt (MW) project.

The Thai connection

Lao PDR’s mountainous topography, numerous tributaries from the Mekong River and relatively high rainfall all lend well to hydropower development, and with 63 dams currently operational, the country expects to have 100 hydropower plants with 28,000 MW of installed capacity by the end of 2020 – nearly enough to power the whole of Thailand for one year.

The Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) has an agreement to buy 95 percent of the electricity produced from the Xayaburi dam from the project’s developers – Xayaburi Power Company Ltd, which is controlled by Thai construction giant, Ch. Karnchang. Six Thai banks funded the 29-year concession project which the Lao PDR government expects to earn almost US$4 billion from.

Hydropower is an increasingly valuable export for Lao PDR – and Thailand is its biggest market – with electricity exports to Thailand surging in value from US$600 million in 2015 to US$1.4 billion last year. However, Lao PDR still has to import electricity due to inefficient national transmission and distribution networks which lose up to 20 percent of power supply according to a report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in July.

In May, Lao PDR’s Ministry of Industry and Commerce said the country plans to spend US$12.1 million on electricity imports this year – mostly from China and Vietnam – while targeting exports of US$1.33 billion, most of it to Thailand. Lao PDR imported US$14.2 million worth of electricity last year, US$11 million of it from Thailand.

As non-governmental organisation (NGO) International Rivers notes, energy experts in Thailand agree that the country does not need Xayaburi’s electricity to meet its growing energy demand.

During a panel discussion on the Xayaburi dam in Bangkok on 22 October, Gary Lee, the Mekong Programme Manager for International Rivers, questioned whether the dam was even necessary.

“According to data on EGAT’s website, this year Thailand has a reserve margin of 30 percent… Which is equivalent to around 12,000 MW of stored capacity,” said Lee. “To put that into perspective, that is equivalent to almost 10 Xayaburi dams.”

‘Heavily favour Thai interests’

International Rivers commissioned an independent analysis on the Xayaburi Dam’s agreement with EGAT which found that while Lao PDR promoted the project as a way to help generate revenue, the agreement was “found to heavily favour Thai interests, while placing significant risk and liability on the Lao government and its people.”

Delays in construction would require the Xayaburi Power Company to pay the Thai government up to US$210,000 per day – one reason why Lao PDR might have pushed forward with the development despite numerous requests by the Cambodian and Vietnamese governments to halt construction in order to allow for further study and consultation.

As Adam Brak, a research assistant at Australian think tank Future Directions International pointed out in an article last year, even when the Laotian government finally takes ownership of dams such as Xayaburi, maintenance and upgrade costs – combined with potentially more cost-effective and efficient sources of electricity – could mean hydropower will not be a lucrative revenue stream.

“Studies have found that every country in the Greater Mekong region theoretically has access to energy sources that are 100 percent renewable, through hydro, wind, solar and hybrid systems,” wrote Brak last year.

“These projections all indicate that, despite currently booming energy requirements for the growing populations surrounding Lao PDR, hydroelectricity may not be as profitable an export in 20 years.”

Related articles:

Damming the Mekong to environmental hell