On a stretch of the Ayeyarwady river, also known as the Irrawaddy river, near Myanmar’s Mandalay, fishermen from six villages work hand-in-fin with 26 Irrawaddy dolphins in a unique collaboration. Taught to do so since childhood, the fishermen cooperatively fish the river with the assistance of the dolphins. The tradition, origin unknown, is said to have been in practice since the 1860s.

The fishermen summon the dolphins by tapping a pointed stick on the side of their wooden boats while making a cooing sound. The dolphins herd fish in the surrounding waters towards the boat. A wave of their tails above the water signals to the fishermen that it is time for the net to be cast. When practising this cooperative fishing technique, the fishermen are said to be able to catch six times more fish than when done individually. The dolphins also benefit from the easy catch of fish that escape the net.

Fragmented and critically endangered

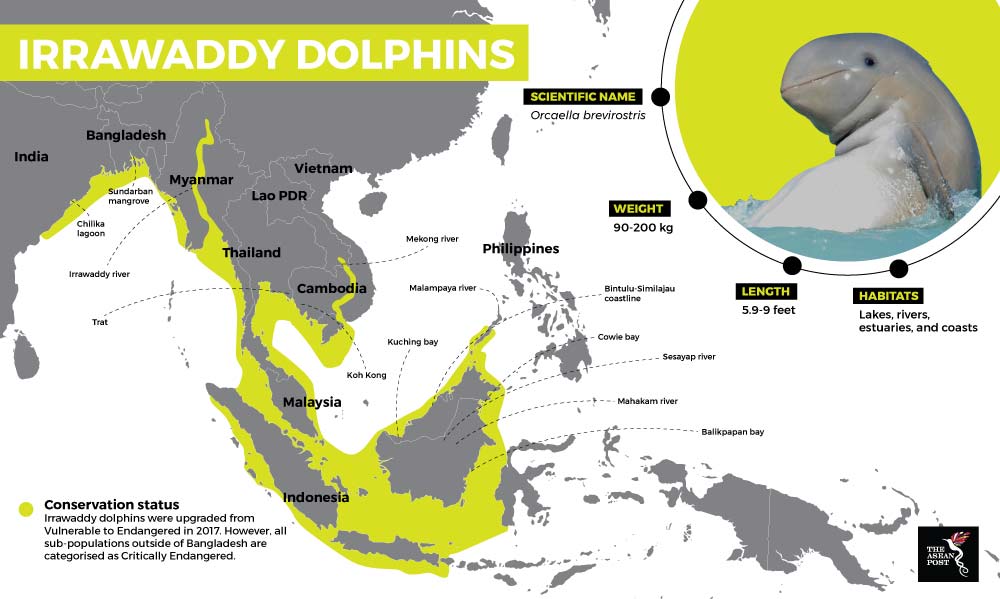

The Irrawaddy dolphins are one of the few species of freshwater dolphins in the world, with fragmented distribution in South and Southeast Asia’s fresh and brackish waters. The species is highly vulnerable to extinction due to incidental mortality as bycatch through the use of gill nets, other destructive fishing practices, habitat degradation, pollution, diversions and damming of rivers for hydropower.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), only an estimated 6,000 Irrawaddy dolphins are left in the wild. The largest population estimated at 5,800 individuals and categorised as endangered, is found in Bangladesh's Sundarbans mangrove forest and in the nearby waters of the Bay of Bengal. However, other sub-populations found in the Ayeyarwady river of Myanmar, the Mahakam of Indonesian Borneo, and Cambodian/Lao PDR’s Mekong, ranging from tens to hundreds, have been categorised as critically endangered.

In 2018, a survey by the government and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) of Cambodia found an increase in the Mekong sub-population, from 80 in 2015 to 92. This has been attributed to a combination of effective patrolling by teams of river guards and strict measures against destructive fishing methods such as use of gill nets and dynamite fishing. Like their counterparts in the Mekong, the Ayeyarwady dolphins are also making a small albeit very welcomed comeback. In February this year, conservationists in Myanmar reported a 10 percent increase of the surveyed population to 76, up from 69 the previous year. It is the highest recorded tally so far.

Source: IUCN.

Thanks for all the fish

With declining river fish stocks in the Ayeyarwady river, a new cooperation has developed, involving the fishermen, dolphins and eco-tourism. In a limited community-based eco-tourism program championed by Myanmar's Department of Fisheries and Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), eco-tourists pay US$40 for a cooperative fishing demonstration.

The demonstration, which is restricted to two hours a day to avoid stressing the dolphins, also offers an on-boat two-day return trip and accommodation from Mandalay. To ensure village-wide incentives for supporting the conservation activities to protect the dolphins, the program also procures meal providing services from households in the village.

The enhanced fish landing and eco-tourism-based sustainable livelihood opportunities afforded through the program, have magnified the benefits of species conservation for Myanmar beyond the rebounding population. So much so that the government has announced a second protected area on Ayeyarwady, further upriver, which stretches 120 kilometres from Sagaing to Shwegu in Kachin State.

Other fisher communities along the river, separated by natural barriers in the flow, have also shown interest in learning cooperative fishing skills. According to WCS’ senior technical adviser Alex Diment, some of the experienced cooperative fishermen who learnt this technique from their fathers and grandfathers are now travelling to other villages and are helping fishermen learn how to fish with the dolphins.

The benefits of Irrawaddy dolphin conservation go beyond the survival of the species. Collaborative conservation actions have resulted in an increase in the population of the highly vulnerable species. However, it should be noted that many of their habitats are incredibly threatened by human activities such as land development, upstream water diversions for hydropower and pollution, as well as climate change. The extinction of the Yangtze’s Baiji dolphin should serve as a constant reminder for us to act now.

Related articles:

Developing an appetite for whale conservation

Building a refuge where trawlers now ravage Cambodia’s marine life