The Philippines is Asia's worst stock and currency market this year. A 6 percent slump in the benchmark index combined with a 4.6 percent slide in the peso means U.S. dollar-based investors are looking at double-digit losses. Year-to-date, foreigners pulled more than $580 million from shares, after inflows of $1.1 billion in 2017.

Analysts aren't telling clients to buy the dip. JPMorgan Chase & Co.'s equity strategy team last week downgraded the country to "underweight" after the Philippine central bank held its benchmark rate unchanged at 3 percent.

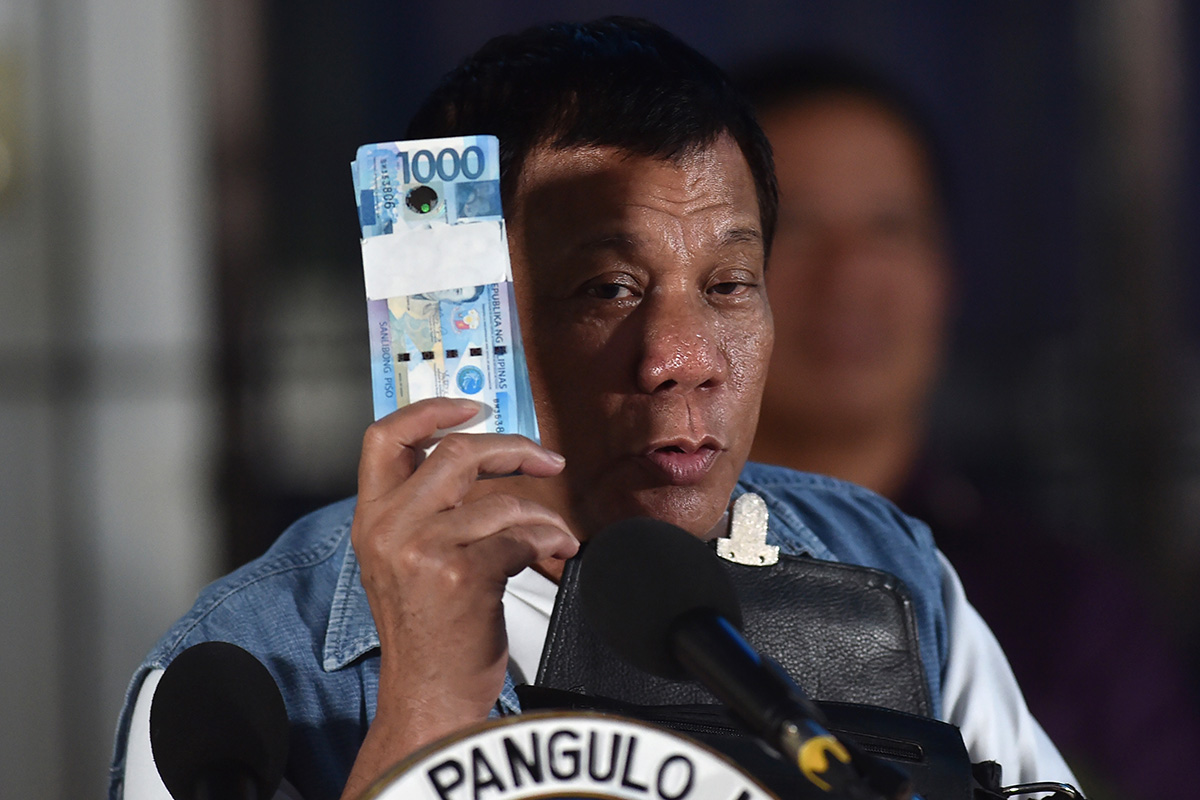

Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas is now seen as behind the curve on inflation. Consumer prices ticked up sharply in the first two months, to 4.5 percent in February, in part because Duterte's tax reform bill caused a jump in prices of day-to-day products such as petroleum, cigarettes and soft drinks.

More importantly, remittances from overseas workers, which account for about 10 percent of GDP, are slowing. On a 12-month moving average basis, payment growth in January came in at only 4.5 percent, down from 5.8 percent pace a year ago. A higher cost of living, along with slowing household income, could spell trouble for domestic consumption, a theme that had attracted foreign investors.

To make matters worse, money transfers may slow further. Last month, the Duterte government said it may expand to other Gulf nations a ban on Filipino maids working in Kuwait, where a domestic helper's body was found in a freezer. Between 2014 and 2016, 63 percent of the country's 4.5 million overseas workers went there, mainly to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Such action would threaten to choke off a major growth engine and worsen the Philippines' current account deficit, dragging on the peso.

Duterte has a point, though. The Middle East is no place for these workers. Despite employing 2.9 million Filipinos, the region accounts for only 25 percent of the total cash sent back home, estimates Malayan Banking Bhd. By comparison, the just over 60,000 Filipinos employed in the U.S. send back 35 percent of the total. Even Asia -- essentially Hong Kong and Singapore -- are the source of 17 percent of cash remittances despite employing fewer than half as many helpers as the Gulf states.

Kuwait is poised to raise the minimum salary of Filipino helpers to $400 a month -- still about 30 percent less than in Hong Kong.

Duterte can't be blamed entirely for the weak peso. If the street view is that the currency is only going down, then overseas workers, whose wages are essentially pegged to the greenback, will remit income only when absolutely necessary. That further depresses payments and the current account.

And the president has a trump card: China. In the past year, the peso has depreciated 12.7 percent against the yuan, the most among its Southeast Asian peers. Duterte counts China as a key ally, and his archipelago nation offers a choice of exotic and affordable islands to tourists from its neighbor. Morgan Stanley estimates the number of Chinese visitors to the Philippines will grow 30 percent this year, following a 35 percent increase in 2017.

As long as Duterte continues courting China and keeps its beautiful Boracay island open, the Philippines is down but not out.