While the ICC’s preliminary examination against Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte for crimes against humanity is unlikely to change his stance on the war against drugs, much debate also exists as to whether the case will eventually see the light of an actual investigation.

“It will not stop the war on drugs. ICC (International Criminal Court) or no ICC it will proceed until the last day of my term,” said President Duterte in a speech at the Petron-Petron Dealers Association (PETDA) Mindanao Mini Convention at the SMX Convention Center in Davao City recently. He had earlier declared that he was beyond the ICC’s jurisdiction because the Rome Statute has not yet been integrated into local laws.

The International Criminal Court was established under the Rome Statute in 2002 and has tried or is in the course of trying 25 cases with 42 defendants thus far, according to its website. While a conviction could result in imprisonment of up to 30 years, very few convictions have actually been made so far.

Article 7 of the Rome Statute lists a series of actions under its jurisdiction for "crimes against humanity", including that of murder. The legislation also clearly states that such an act, in order to be prosecuted as a crime against humanity, has to be committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack. The existence of an express or implied state policy to commit such acts against a particular or identifiable civilian population also needs to be proven.

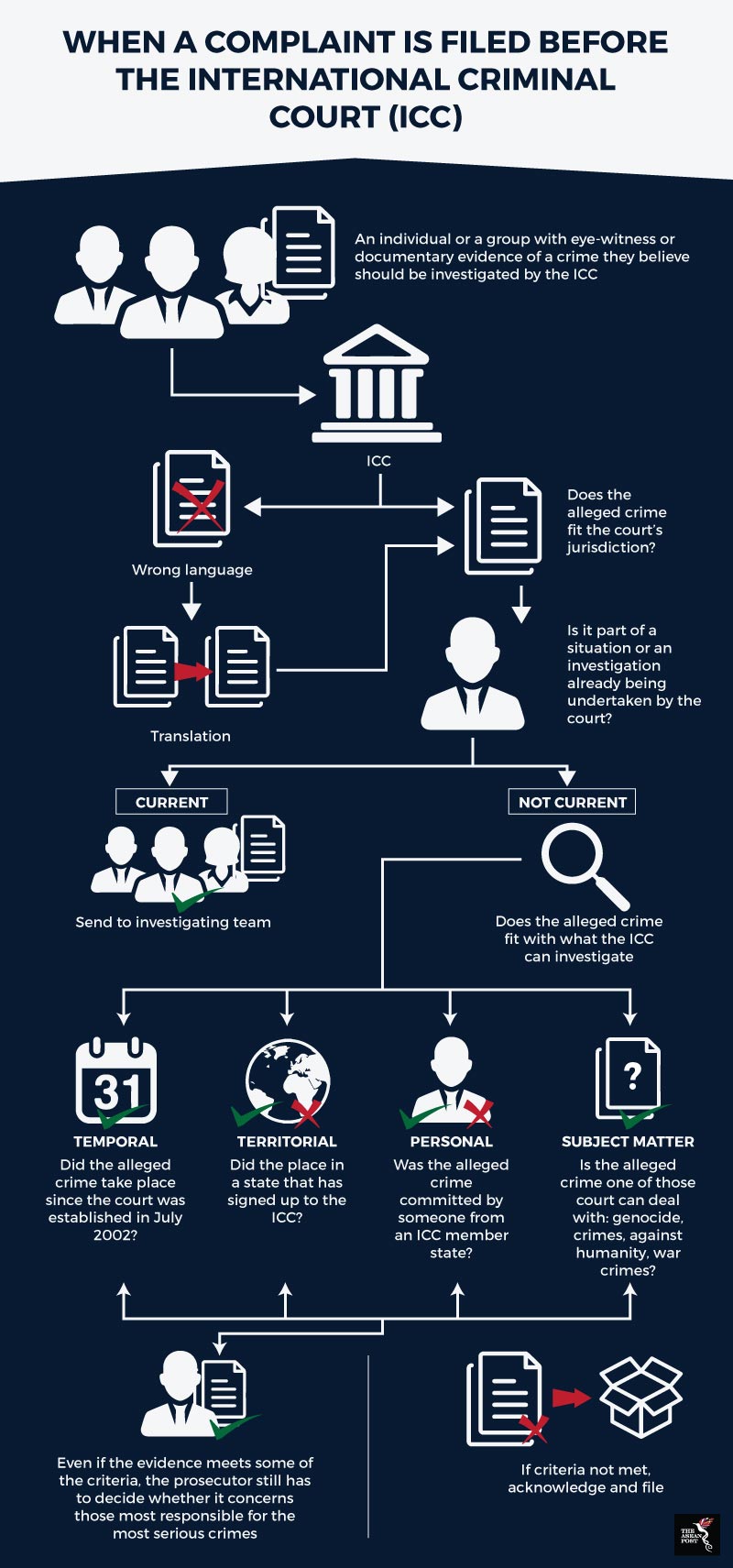

Source: Justice Hub

The ICC preliminary examination against Duterte was opened in early February 2018 in order to review whether crimes against humanity had been committed during the course of his administration and whether the ICC may have the jurisdiction to bring those crimes to trial.

ICC chief prosecutor Fatou Bensouda said in a statement that the preliminary investigation would “…analyse crimes committed since at least 2016 in the context of the ‘war on drugs’ campaign”, according to reporting by The Guardian. A full investigation will only be warranted if two conditions are satisfied: namely, that an ICC crime had been committed, and that the state in which the crime was committed is unlikely to proceed with investigating the offence.

The Philippine Star reported earlier this month that in response to the news that the ICC was pursuing a preliminary examination, Duterte’s supporters were reported to have trolled the ICC’s Facebook page with comments that they would defend their president at all costs.

Even when conducting the preliminary examination, the ICC might encounter some barriers to proving the case against Duterte ‘beyond reasonable doubt’. Previously, even though rights groups such as the Commission on Human Rights had sought to investigate the drug war related deaths, such efforts failed due to a general lack of cooperation from other government agencies and limited resources to fund such investigations, Channel News Asia reported earlier this month.

Meanwhile Harry Roque, the Philippine presidential spokesperson pointed out in a radio interview recently that since there was no formal investigation yet in place, the ICC could not yet request for documentation from the Philippine government.

Even though the Philippines is legally obliged to cooperate with the court’s preliminary examination it has few mechanisms to enforce this obligation.

Alex Whiting, Harvard Law Professor and former ICC investigation and prosecution coordinator told Rappler in 2017, “Essentially, its sole recourse is to complain to the judges who can then make a finding of non-cooperation and refer the matter to the Assembly of States Parties.”

On the other hand, Philippine citizens have alleged that there remain few alternative avenues for them to turn to for objective solutions. The recent 32nd commemoration of the Edsa People Power revolution on 25 February saw even more protestors take to the streets to protest Duterte’s regime, which they alleged as having made the historical ouster of dictator Ferdinand Marcos pointless.

“We believe that we need an institution that is free from threats, that is independent enough to look into the case of extrajudicial killings in the country,” opposition politician Gary Alejano told The Rappler in February 2018. He was referring to the ICC’s exercise of jurisdiction on the matter. Extrajudicial killings, according to the Oxford Dictionary, are killings that are done without the sanction of the legal system.

Although it is at present unclear whether the ICC case against Duterte will eventually advance to the stage of an actual investigation, one thing remains clear: that such a drug war will not be resolved overnight. The response Duterte gave when Canada chose to conduct a review on a US$300 million helicopter sale simply prompted him to cancel his order outright, demonstrating that international sanctions is unlikely to deter him either. It certainly looks like there are long days ahead where this issue is concerned.