As if human rights abuses, corruption charges and deadly landslides haven’t hurt the industry enough, Myanmar’s multi-billion-dollar jade and gemstone industry now has to deal with the challenges of e-commerce.

Myanmar produces 90 percent of the world’s jade and is a major player in the global gem economy, but poor regulations mean up to two-third of the country’s production is possibly not subjected to tax according to a report by the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) in March.

The increasingly affluent China is the biggest market for Myanmar’s jade, and Radio Free Asia has reported how the highly valuable stone is often smuggled untaxed across porous borders to Chinese buyers – and the direct sale of jade online may now make up about 80 percent of all purchases, bypassing Myanmar’s tax collectors.

Myanmar Gems and Jewellery Entrepreneurs Association vice chair, U Zaw Bo Khant, noted in an interview with Myanmar media in August that the high tax rate on jade and gems – which can reach up to 15 percent – meant “a lot of the gemstones are smuggled out to China.”

The undervaluing of registered jade and gemstones costs Myanmar billions of dollars in lost tax revenue, and even when the sales are conducted in Myanmar, online transfers via Chinese payment platforms such as Alipay and WeChat Pay result in further revenue loss.

“The rising trend of illegal and low-quality goods being posted for sale on WeChat at impossibly low prices is a big deal and has to be controlled,” Ko Aung San Oo, manager of Shwe Phyo Oo Gem and Jade Shop, told Myanmar media earlier this month.

“The authorities should know that legal businesses that pay tax and promote high-quality, Myanmar-produced jewellery and gems will suffer. Already, there are less Myanmar traders selling high-quality jewellery … Everything is low-quality and this reputation is bad for the country,” he said.

Poor reputation

Myanmar’s jade industry already has a less than savoury reputation as it is.

The Hpakant region in Kachin state, where up to 90 percent of the world’s jade is mined, has seen hundreds of deaths over the past few years due to landslides in the mines.

Forced labour is rife, and mining corporations have been blamed for land grabs in areas rich in jade and gems – where the toxic discharge from mining operations have long polluted water sources.

Private mining operators have been accused of bribing their way into obtaining mining licenses, and a complex system of patronage and cronyism ensures these mine operators escape punishment – with the jade industry also a valuable revenue stream for the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) which controls the area and the smuggling routes into China.

Chinese connection

Ruili, a city in Yunnan province on China’s border, its known by jade traders for its Yangyanghao Taobao Raw Jade Trade Market co-organised by the Chinese government and Taobao – the country’s largest e-commerce platform.

The market – a former jade museum – is notable for being the only one in the country to offer online auctions and trades in raw jade through livestreams, with Chinese media reporting in April that monthly sales in March exceeded 400 million yuan (US$56.5 million) with the most expensive piece costing 660,000 yuan (US$93,200).

The Ruili government estimates that there were more than 20,000 livestream broadcasters from across the country in the city at the end of 2017, with the market even extending its business hours to midnight to cater to growing demand.

However, as with any other online shopping exercise, there are risks involved in buying jade over the internet.

There have been numerous cases of fraud reported in which sellers shipped worthless stones instead of pricy jade after deals were agreed.

Data discrepancy

Frustratingly, discrepancies in data make it hard to ascertain the exact figure lost through fraud – or the total size of the industry for that matter.

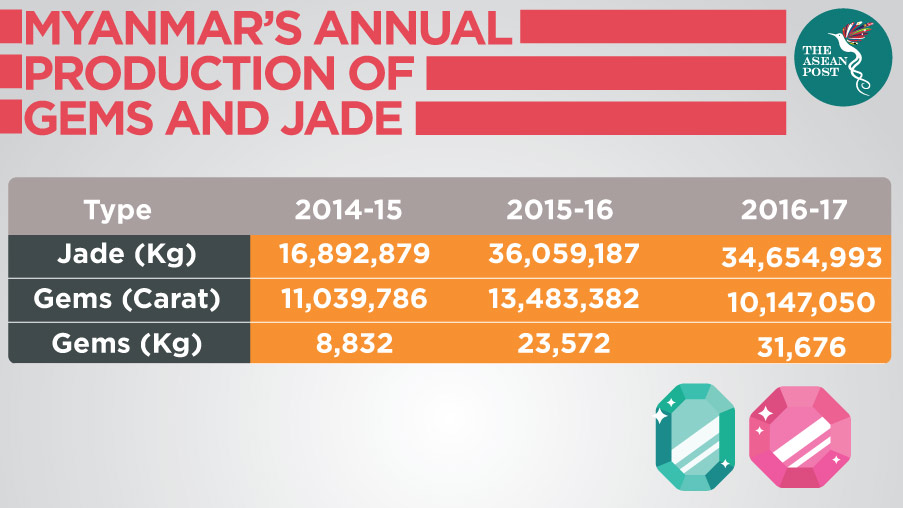

Myanmar joined the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) in 2014, a global standard for the good governance of oil, gas and mineral resources based in Norway which requires its members to publicly disclose their revenues from extracted resources. Myanmar submitted EITI reports for fiscal years 2014-15 and 2015-16 last year, with NRGI observing that these disclosures have been extremely limited in scope and accuracy.

“Nearly half of jade and gemstone company data shared from these reports was missing, incomplete, or irreconcilable with government data,” it stated in a report published in February.

“Moreover, after interviewing industry stakeholders, NRGI believes that the Myanmar government only collected government revenue on two to five percent of production value,” added the report.

Myanmar Gems and Jewellery Entrepreneurs Association’s U Zaw noted how tax in sales from government-organised emporiums, where most formal – and therefore taxable – sales of jade and gemstones occur, decreased from US$300 million in the 2013-14 fiscal year to US$200 million in 2014-15 and US$190 million in 2016-17.

On the production side, mine operators often under-report their annual numbers as they try to evade paying taxes, and while Myanmar registered selling an average of US$1.2 billion a year worth of jade between 2012 and 2016 at its emporiums, China reported importing US$2.6 billion over the same period.

NRGI data, meanwhile, states that Myanmar’s jade production alone was between US$3.7 billion and US$43.1 billion for the 2015-16 fiscal year.

With such huge inconsistencies, it may be near impossible to determine exactly how much of Myanmar’s jade trade is moving online and how this will hurt one of the most crucial revenue streams for the government.

Related articles: