Food has an environmental impact. A 2018 study by J. Poore and T. Nemecek titled ‘Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers,’ published by the University of Oxford revealed that food production is responsible for 26 percent of all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, contributing to global warming. The study showed that animal products contribute 58 percent of food-related GHGs.

This environmental impact will likely worsen due to rising meat consumption that is driven by growing wealth and urbanisation.

Asia’s seafood and meat consumption will increase by 78 percent in 2050, according to an Asia Research and Engagement’s (ARE) report titled ‘Charting Asia’s Protein Journey’ in 2018. The study revealed that the Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand would lead demand growth, while Indonesia’s meat consumption will overtake India’s by 2036 at around 7.5 million tonnes.

In 2017, nutritionists at the National Heart Institute (IJN) in Malaysia said that Malaysians were consuming too much animal products.

Animal farms

Livestock farming contributes to global warming by producing considerable GHGs. As reported by the United Nations (UN) Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 30 percent of the Earth’s landmass is used to raise animal food, where clearing land for pastures releases carbon dioxide (CO2) at a staggering rate. The other half of the Earth’s land is used for growing crops to feed animals.

Animal farming is a threat to our water supply too, using 70 percent of the water available to humans. As the demand for meat increases, there will be less water available for both, crops and drinking. The fertilisers and pesticides used for plants also pollute waterways, causing ‘dead zones’ in seas, while animal waste ends up contaminating waterways and groundwater.

Cows and sheep also release large volumes of methane, which is 30 times more potent as a heat-trapping gas.

Meatless option

The pressure on the environment is forcing consumers to rethink their consumption habits. They are now better informed of the food system and are more conscious about what they eat and where their food is sourced from.

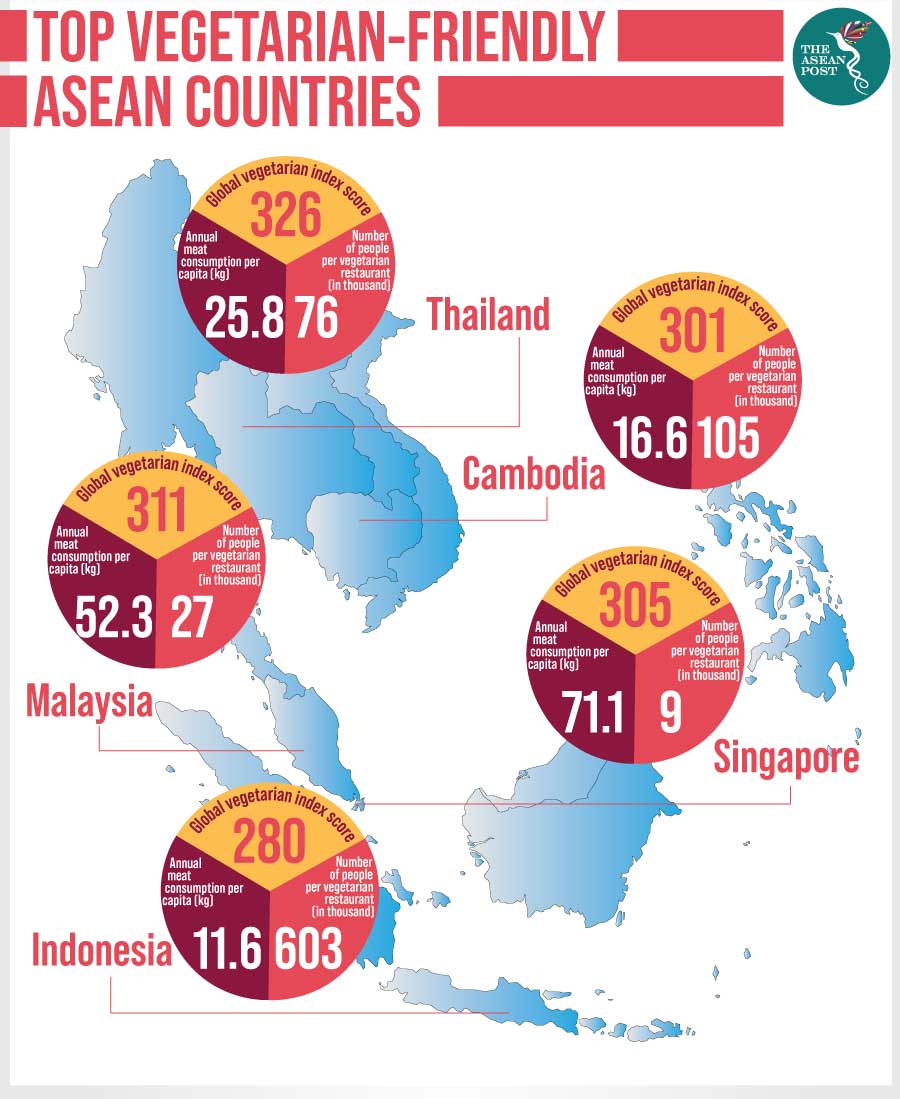

The understanding that a healthier diet can reduce the environmental impacts of the food system, fuels the vegetarian and vegan movement. Across Southeast Asia, there is an increase in the number of vegetarians and vegans, evident from the increasing number of vegan restaurants and products in the market.

“In Malaysia, there is an uptick in the number of vegans in Malaysia,” said Prabha Shanmugam, general manager of Kawkawveg, a cloud kitchen serving vegan food. She concedes that while being vegan in Malaysia is possible; it still has its challenges.

“Care has to be taken to ask only to use non-animal products. The trickiest ones are butter and milk as their use is so ubiquitous that they often go unnoticed. However, alternative milk sources are on the rise, and some restaurants are progressive enough to cater to the needs of vegans without too much of a fuss,” explained Shanmugam.

For Shanmugam, ‘fake meat’ products are an excellent replacement that makes it easier for a meat-eater to transition towards a vegan diet. Plant-based fake meats now resemble real meat in taste and texture. Yet, these mock meats are sometimes manufactured with additional unhealthy additives, and there is nothing healthy about a vegan hotdog if they are just another form of overly processed industrial foods.

Veganism may not be for everyone given the cultural, political and financial state of our world. One cannot expect indigenous people to go vegan, specifically those who live off the land, or people who follow religious practices. Dietary changes are difficult in a society whose food culture is centred on meat and animal products.

Adhering to any diet also requires the privilege of choice. Thus, poverty is a huge deterrent for potential vegans. In low-income neighbourhoods, healthier food and vegetables can be more expensive than meat and animal products. And for the poor in Southeast Asia, fake meats can cost a fortune.

A vegetarian or vegan diet can also run the risk of deficiencies in essential nutrients such as iron, calcium and vitamin B12.

Flexitarianism

According to a 2018 study in the Nature Journal by Springmann et al., people need to eat 75 percent less meat on a global average to prevent a climate breakdown. But to help save the planet, one does not have to forgo meat altogether. Flexitarianism or a ‘casual vegetarianism’ diet highlights an increased intake of plant-based meals without eliminating meat. Eating a diet that reduces red meat consumption can also lower the risk of heart disease.

“Every little step towards meat reduction counts. Can’t go fully, vegan? Go vegetarian? Can’t go vegetarian? Go flexitarian. The result is still a reduction in the consumption of meat, and that’s great,” Shanmugam said.

Developments in food technology are encouraging consumers to eat healthier plant-based foods. But halving food waste and improving farming is also important. The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), said that if land is used more effectively, it can store more of the carbon emitted by humans. Until more sustainable farming can be achieved, we should at least try cutting down on our meat consumption.

Related articles: