As digital technologies and automation have advanced, fears about workers’ futures have increased. But, the end result does not have to be negative. The key is education.

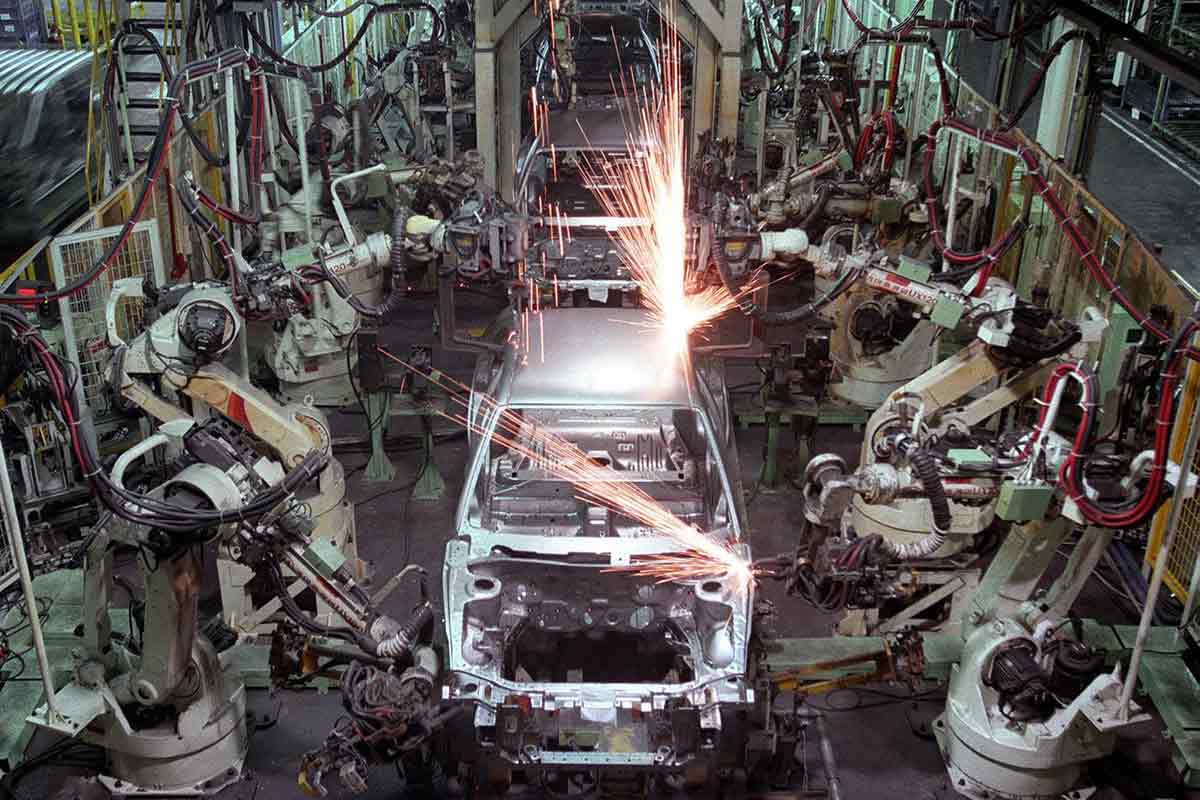

Already, robots are taking over a growing number of routine and repetitive tasks, putting workers in some sectors under serious pressure. In South Korea, which has the world’s highest density of industrial robots – 631 per 10,000 workers – manufacturing employment is declining, and youth unemployment is high. In the United States (US), the increased use of robots has, according to a 2017 study, hurt employment and wages.

But while technological progress undoubtedly destroys jobs, it also creates them. The invention of motor vehicles largely wiped out jobs building or operating horse-drawn carriages, but generated millions more not just in automobile factories, but also in related sectors like road construction. Recent studies indicate that the net effects of automation on employment, achieved through upstream industry linkages and demand spill overs, have been positive.

The challenge today lies in the fact that the production and use of increasingly advanced technologies demand new, often higher-level skills, which cannot simply be picked up on the job. Given this, countries need to ensure that all of their residents have access to high-quality education and training programs that meet the needs of the labour market. The outcome of the race between technology and education will determine whether the opportunities presented by major innovations are seized, and whether the benefits of progress are widely shared.

In many countries, technology has taken the lead. The recent rise in income inequality in China and other East Asian economies, for example, reflects the widening gap between those who are able to adopt advanced technologies and those who aren’t. But education-job mismatches plague economies worldwide, partly because formal education fails to produce graduates with skills and technical competencies relevant to the labour market.

In a report by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), 66 percent of executives surveyed were dissatisfied with the skill level of young employees, and 52 percent said a skills gap was an obstacle to their firm’s performance. Meanwhile, according to an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) survey, 21 percent of workers reported feeling over-educated for their jobs.

This suggests that formal education is teaching workers the wrong things, and that deep reform is essential to facilitate the development of digital knowledge and technical skills, as well as non-routine cognitive and non-cognitive (or “soft”) skills. This includes the “four Cs of 21st century learning” (critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, and communication) – areas where humans retain a considerable advantage over artificially intelligent machines.

The process must begin during primary education, because only with a strong foundation can people take full advantage of later education and training. And in the economy of the future, that training will never really end. Given rapid technological progress, improved opportunities for effective lifelong learning will be needed to enable workers to upgrade their skills continuously or learn new ones. At all levels of education, curricula should be made more flexible and responsive to changing technologies and market demands.

One potential barrier to this approach is a dearth of well-trained teachers. In Sub-Saharan African countries, for example, there are some 44 pupils for every qualified secondary school teacher, on average; for primary schools, the ratio is even worse, at 58 to one. Building a quality teaching force will require both monetary and non-monetary incentives for teachers and higher investment in their professional development.

This includes ensuring that teachers have the tools they need to take full advantage of information and communication technology (ICT), which is not being used widely, despite its potential to ensure broad access to lifelong learning through formal and informal channels. According to the EIU report, only 28 percent of secondary-school students surveyed said that their school was actively using ICT in lessons.

ICT can also help to address shortages of qualified teachers and other educational resources by providing access across long distances, via online learning platforms. For example, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s OpenCourseWare enables students around the world to reach some of the world’s foremost teachers.

This points to the broader value of international cooperation. The education challenges raised by advancing technologies affect everyone, so countries should work together to address them, including through exchanges of students and teachers and construction and upgrading of ICT infrastructure.

All efforts to bolster education should emphasize accessibility, so that those who are starting out with weaker educational backgrounds or lower skill levels can compete in the changing labour market. Well-designed and comprehensive social safety nets – including, for example, unemployment insurance and public health insurance – will also be needed to protect vulnerable workers amid rapid change.

The artificial intelligence revolution will be hugely disruptive, but it will not make humans obsolete. With revamped education systems, we can ensure that technological progress makes all of our lives more hopeful, fulfilling, and prosperous.

Lee Jong-Wha is Professor of Economics and Director of the Asiatic Research Institute at Korea University. His most recent book, co-authored with Harvard’s Robert J. Barro, is Education Matters: Global Gains from the 19th to the 21st Century.