Social institutions such as education, healthcare and public housing services play a key part in a country’s soft infrastructure.

Apart from roads, bridges, airports and other hard infrastructure projects needed to sustain growth across the region, soft infrastructure initiatives are just as crucial in developing knowledge, innovation and technical know-how.

As a whole, the region has prospered over the past two decades with the “manufacturing for export” strategy as the main pillar in most countries.

However, as the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO) notes, the transformation to services is inevitable and the issue of investment in the requisite areas to generate and sustain growth will need to be addressed.

AMRO is a regional macroeconomic surveillance organisation that aims to contribute to securing the macroeconomic and financial stability in the ASEAN+3 (China, Japan and Korea) region.

Invest more in education

While ASEAN countries are implementing Fourth Industrial Revolution – or Industry 4.0 – technologies, they have yet to roll out substantial changes to education policies thanks in part to funding gaps.

“All the existing policies are geared towards Industry 3.0,” AMRO Chief Economist Dr Khor Hoe Ee told The ASEAN Post.

“We need to invest more in education and encourage the development of more valuable skill sets, critical thinking and life-long learning if we are to succeed in this new (digital) economy,” he added.

Since education is a long-term investment, its rewards may not be apparent for decades to come – which has made it less of an attractive proposition, especially in ASEAN’s developing countries.

This view is supported by the World Bank, which in its ‘World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work’ report stated that one reason governments do not invest in human capital is the lack of political incentives.

There is limited data available on whether health and education systems are generating human capital. This hinders the design of effective solutions, the pursuit of improvement and the ability of citizens to hold their governments accountable.

The World Bank defines human capital as the knowledge, skills and health that people accumulate over their lives, enabling them to realise their potential as productive members of society.

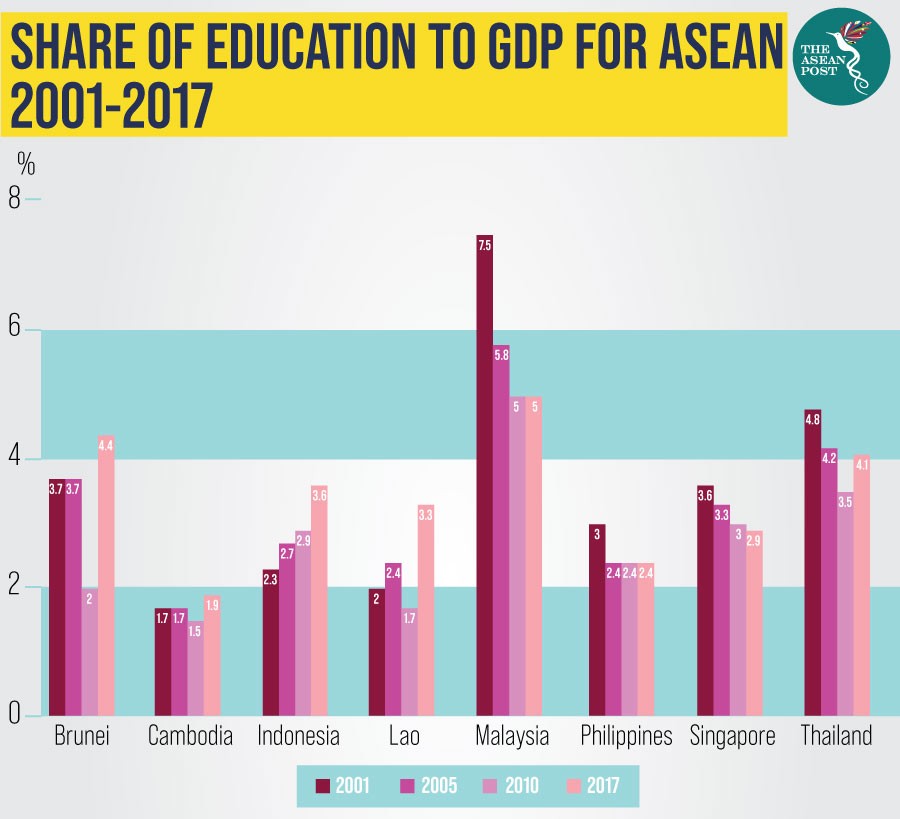

As the ASEAN Secretariat notes, expenditure on education is an investment in human capital as it contributes towards skill formation, which raises the ability to work and to produce – and thus contributes to economic growth.

Funding gap in CLMV

Technology is disrupting the demand for skills globally, resulting in the need for relevant education policies that can cater to the changing landscape effectively. However, with access to funding in short supply in developing countries, education stakeholders need to tackle this issue first before lobbying for better education policies.

Funding gaps which arise from low savings rates in developing countries relative to their investment needs was identified in AMRO’s Regional Economic Outlook 2019 report titled ‘Building Capacity and Connectivity for the New Economy’ as one of the challenges these countries face in improving their infrastructure capacity.

In ASEAN, the funding gap is most acute among the CLMV (Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam) economies, where domestic savings are insufficient for the necessary catch-up in infrastructure investment.

In Cambodia, Lao PDR and Myanmar, the chronic underinvestment in education – combined with low healthcare spending and the limited availability of skilled labour – are issues which have yet to be fully addressed.

The global annual funding gap for education amounts to nearly US$40 billion, and United Nations (UN) Deputy Secretary-General Amina J. Mohammed has called for increased domestic financing and a renewed commitment from international donors to help close this gap.

However, general spending on education isn’t as important as the specific areas it is being spent on.

Specialised skills

“We need more specialised skill sets, it can’t be a ‘one size fits all’ kind of thing,” stressed Dr. Hoe.

“Take for the example the Philippines, where business process outsourcing (BPO) now have academies to certify companies, and they have tests to make sure they pick call centre operators who don’t have pronounced accents… It’s getting more specialised,” noted the economist.

Institutes like the Asian Development Bank (ADB) are among those that have heeded Amina’s call, and programs such as the recent loan it provided Cambodia to upgrade facilities and equipment of selected technical training institutes help close this funding gap.

ASEAN’s workplaces are undergoing a shift from being labour-intensive to a more skills-and knowledge-based economy, setting the bar higher for the skill sets needed to work with digital technology and customised services in an increasingly connected and complex world.

As Jack Ma, founder of e-commerce giant Alibaba said at last year’s World Economic Forum in Davos, “If we do not change the way we teach, 30 years from now, we’re going to be in trouble.”

Related articles:

Critical thinking needed to upgrade skills