Since sanctions by the United States (US) and European Union (EU) were lifted, Myanmar has enjoyed relatively strong economic growth. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), Myanmar’s economy has grown at an average of 7.5 percent between 2012 and 2017. Its economy is slated to accelerate further, driven by a spike in private and public investment and aggressive consumer spending.

However, for Myanmar’s economic ambitions to come to fruition, it must first solve its energy challenges – primarily, in meeting the demand for power.

Myanmar’s electrification problems

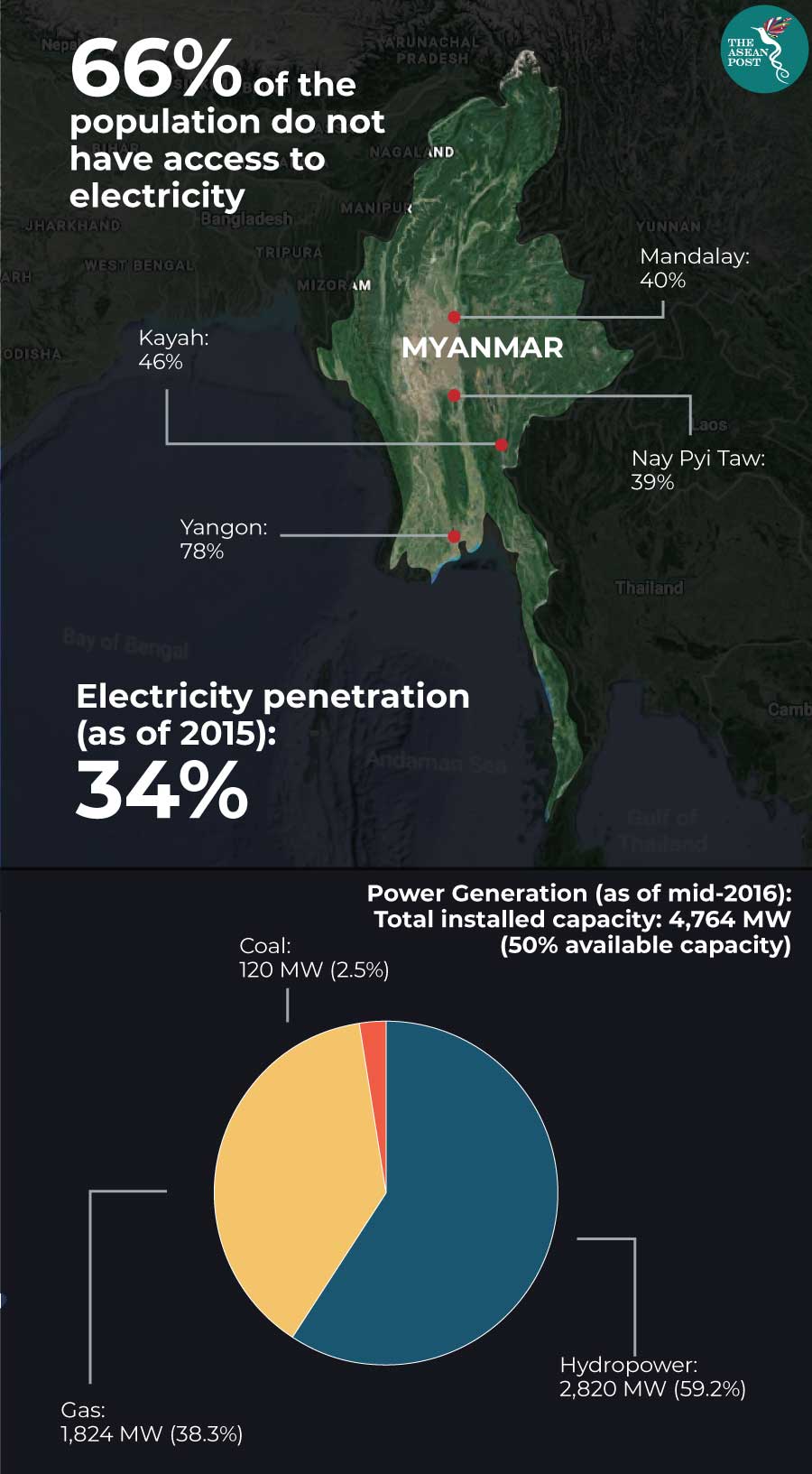

According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), between 2000 and 2012, electricity demand in Myanmar grew by 9.8 percent year-on-year and will continue to grow at a staggering pace. Estimates by the Japan International Co-operation Agency (JICA) – Myanmar’s largest source of official development assistance (ODA) – places electricity demand at approximately 15 gigawatts (GW) by 2030. That translates to a fivefold increase from current levels. Myanmar’s existing installed electricity generation capacity is five GW although its peak capacity is only half of that, at 2.5 GW.

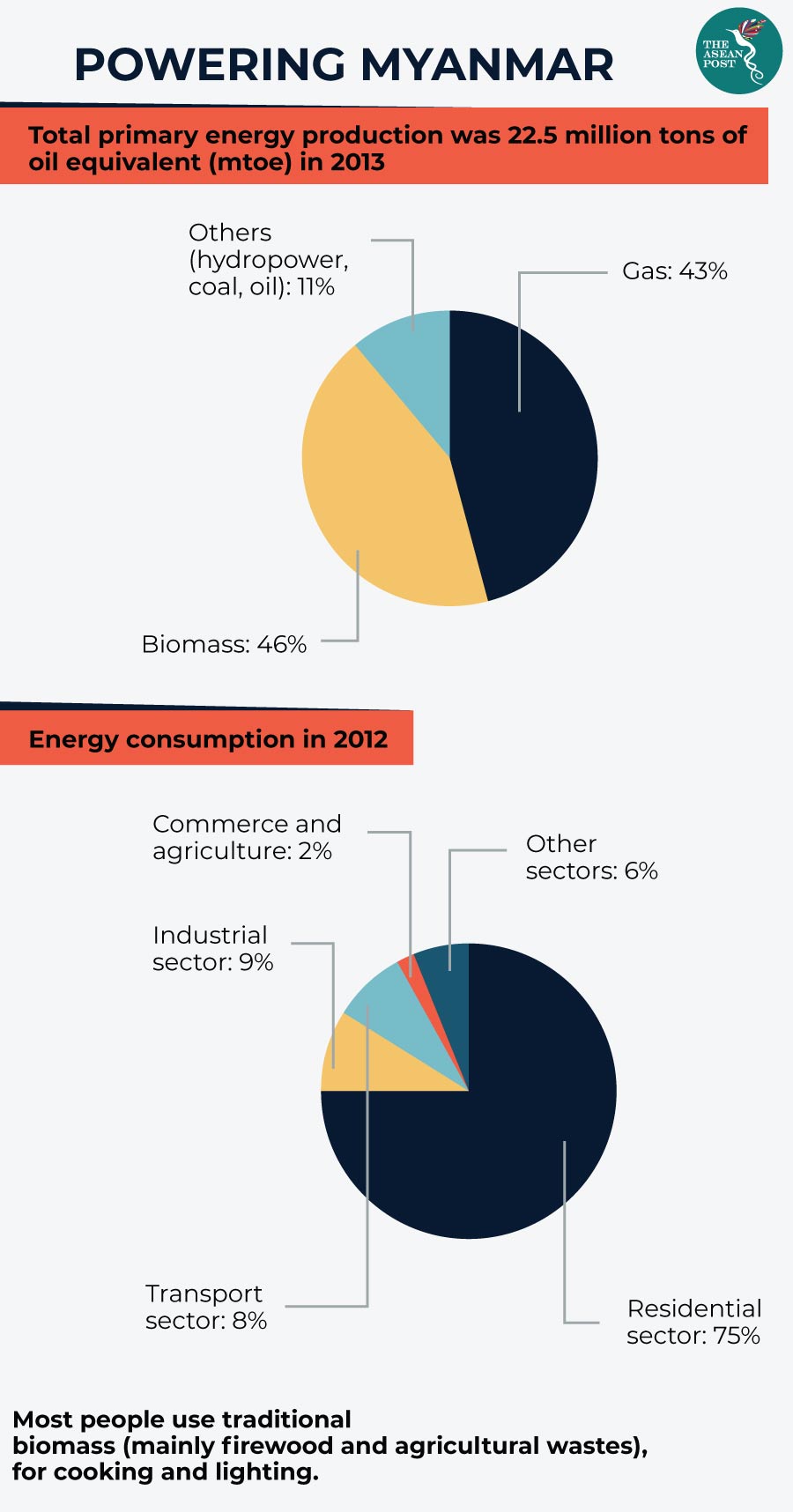

Besides powering burgeoning industries, the increase in electricity demand is also due to Myanmar’s attempt to bridge the electrification gap. For a nation blessed with a wealth of electricity-generating resources, electrification and electricity usage rates are woefully dismal. As it stands, 65 percent of its citizenry do not have access to the national grid. Per capita usage of electricity was just 217 kilowatt hours (kWh) in 2014 according to World Bank numbers – the lowest amongst all member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

While efforts are taken to bridge this gap, energy demand will continue to surge.

Between hydropower and natural gas

Under the National Electrification Plan, Myanmar has set a goal of 50 percent electrification by 2020 and 100 percent by 2030.

The most obvious solution, is to harness the abundance of hydropower available in the country. The ADB estimates this to be in excess of 100,000 megawatts (MW) in terms of installed hydropower capacity.

Dams are already the primary source of Myanmar’s power generation at approximately 60 percent. There are currently 26 state-run hydropower plants in operation with a total installed capacity of 3,181 MW. Another five – a number of which are mega-dams (over 1,000 MW) – are slated for construction but are all currently facing delays.

Hydropower may suffer drawbacks due to the damming of rivers which may affect the livelihoods of people dependent on the water source. For example, the projects which would dam the Irrawaddy and Salween rivers have come under severe criticism by environmental rights groups who claim it would affect downstream land fertility and significantly impact the income of the local people.

The government of Myanmar has turned its focus to natural gas but gas production in existing oil fields are declining. There are fields that are in the early stages of exploration but won’t be ready until after 2020. This leaves the government with a 10-year deficit of gas supply which it must fill if it intends to rely on gas for electricity production. Myanmar’s Ministry of Electricity and Energy (MOOE) has announced plans to commission a liquified natural gas (LNG) terminal which would provide a huge chunk of gas intended for electricity supply until the fields are ready.

Government inexperience and a solar answer

As the country attempts to quench its thirst for electricity, it indirectly opens up room for investment. However, a recent report by The Economist revealed that government inefficiencies often hinder the development of the energy sector in Myanmar.

The MOOE has little experience with public-private partnerships – especially negotiations with foreign investors – as most electrification initiatives are state-run. Besides that, bureaucracy is also to be blamed.

The report also highlighted a mismatch of expectations between government and independent power producers (IPPs). IPPs often approach governments, expecting some sort of guarantee as they undertake such large financial commitments.

“To date, the government has been reluctant to take these steps, resulting in IPPs unable or unwilling to secure the finance without government support, while government counterparts search in vain for completely independent power suppliers,” the report stated.

The door has not completely closed for Myanmar. Its electrification goals can still be attained. But that would require the government to shift its posture on engagement with IPPs and to diversify its sources of energy.

Solar is a likely option. Two projects exceeding 150 MW are currently being constructed and should be monitored as “demonstration projects.” Given that the cost of solar generation has fallen, herein lies an opportunity for Myanmar to bridge the gap in its energy needs. The growing trend of corporate power purchasing agreements (PPA) and projects that are directly financed via long-term contracts with the private sector, is a carrot for solar energy producers as they are not currently impacted by tariffs or subsidy issues.

Related articles: