The elephant is a cultural symbol in Lao probably due to the fact that at one period in time, the country was known to have a large number of these mighty mammals roaming its lands free. So much so that before it was ever known as Lao, people used to call parts of the country Lan Xang or Land of a Million Elephants.

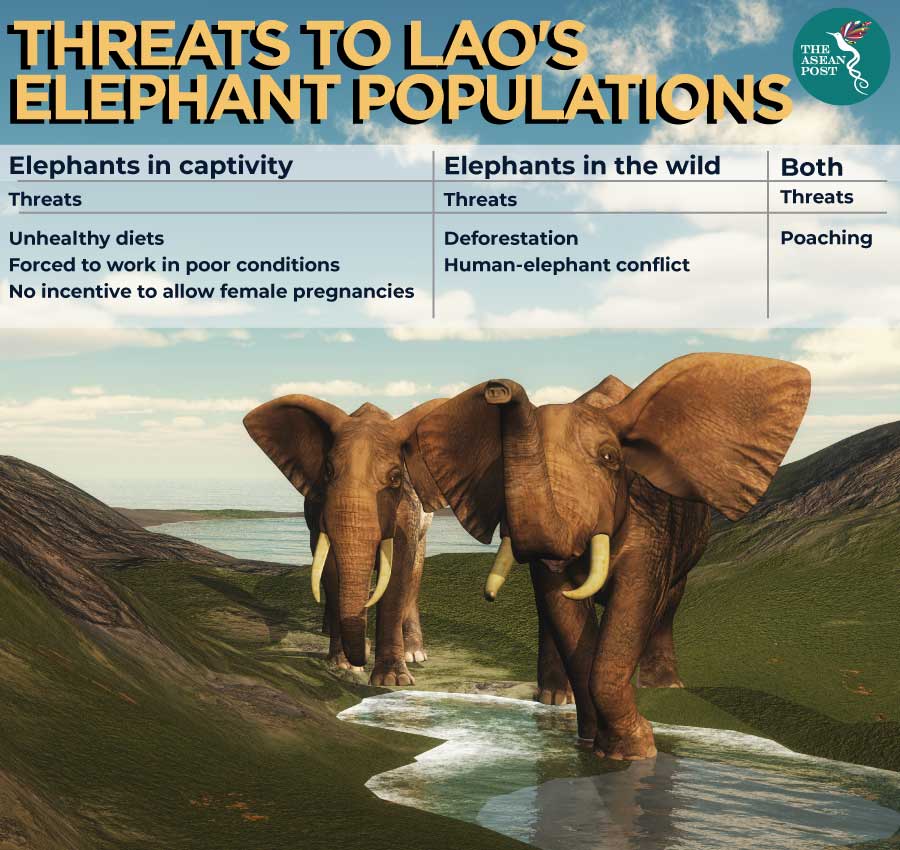

As of last year, however, both the government of Lao and conservation groups believe the robust Asian elephant population the country once boasted of has now dwindled to about 800 where 400 are wild elephants and 400 are in captivity; and even these shrinking populations are under constant threat.

“Both populations are not sustainable and are actually declining. And the problems that each population faces are completely different,” said Anabel López Pérez, wildlife biologist with the Elephant Conservation Center.

Elephants in captivity are at risk as they are fed unhealthy diets, forced to work in poor conditions at elephant tourism camps, or get injured and aren't taken care of properly. To top this all off, López said that elephant owners have little incentive to breed the animals in captivity, as a pregnancy would affect a female elephant’s ability to work for up to four years.

Male elephants are aggressive and tend to be more unpredictable than females due to their hormonal changes. So, elephant keepers prefer not to use them for work.

The situation for elephants running free in the wild isn’t much better either. According to López, the root of the dangers that wild elephants face in Lao stems from deforestation which is exacerbated by the demand for timber coming from neighbouring countries like China and Vietnam. Experts say that Lao, today, has only about 40 percent forest coverage compared to the 70 percent that was recorded in the 1950s.

Deforestation in Lao has led to the fragmentation of habitats and as the elephants are unable to follow their normal migration patterns, this then results in human-elephant conflicts.

"So, elephants go outside the forest and find human infrastructure and crops of the locals. They eat everything around and sometimes break infrastructures, and locals are not very happy with the situation," said López.

Poaching threatens both, domesticated and wild populations. López revealed that the demand for elephant body parts continues to rise in countries like China and Myanmar, where elephant skin and ivory are used in traditional medicine.

Not so green

Earlier in 2018, progress tracking of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development goals for Southeast Asia revealed disappointing outcomes for Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 15. SDG 15 measures forests and forested land protection, restoration and sustainable use.

However, despite the regional trend, Vietnam experienced a resurgence in forest cover over the past few decades, reaching 48 percent as of 2017. Vietnam hit its lowest coverage in 1990 at 27 percent due to the conversion of forested land into farms as well as leftover reactions to bombs and defoliants during the Vietnam War. The improvement has been attributed to the government’s move to restrict timber harvesting and processing for export, reforestation activities and natural regeneration.

Some, however, are calling Vietnam’s improved performance deceptive, achieved at the expense of its neighbours, specifically Lao and Cambodia. Supposedly, Vietnam has left its forests untouched while demanding timber from its neighbouring countries.

If this is true, it would also explain the deforestation in Lao which, as mentioned earlier, is the major threat to elephants living in the wild.

It would be unfair to say that the government of Lao has not tried to tackle the issue of dwindling elephant populations. One of the government’s successful initiatives has been to place tight restrictions on using elephants to transport wood for the logging industry.

Apart from that, the government there has also maintained a healthy relationship with the Elephant Conservation Center which is trying to rehabilitate Lao’s elephant population. Established in 2010, the centre is the country's only conservation park.

Nonetheless, more must be done if Lao hopes to revive its once strong elephant populations. Considering the small number left, time is certainly of the essence.

Related articles: