Shock belts, spiked batons, and electrified thumbscrews can serve no other purpose than to inflict pain on people. But despite the fact that torture is prohibited by international law, goods such as these are still produced and sold, finding their way to buyers around the globe.

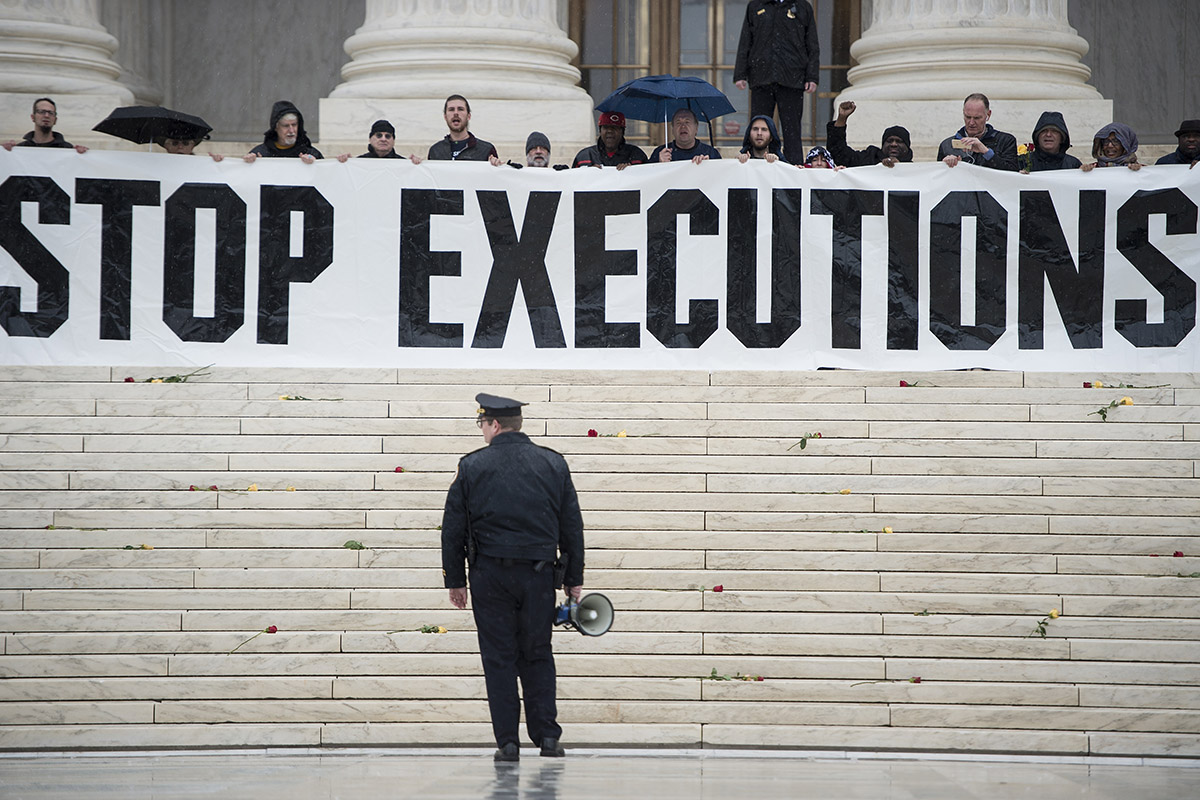

Likewise, at a time when more countries are abolishing capital punishment, the products used to carry out death sentences – such as lethal-injection systems, poison cocktails, electric chairs, and gas chambers – remain on the market. According to Amnesty International, nearly 19,000 people worldwide are awaiting execution, even though capital punishment has no proven effect as a deterrent and makes judicial errors irreversible.

If we in the international community are serious about ending torture and abolishing capital punishment, we must do more than make lofty promises. It is time for concrete action to make acquiring the means of execution and torture far more difficult.

On September 18, when delegates from around the world gather for the United Nations General Assembly in New York, a large group of countries will commit to creating a new global framework to end this despicable trade. By joining a new Alliance for Torture-Free Trade, governments will agree to establish national export bans on products used for torture or executions, while further empowering their customs authorities to enforce the prohibitions.

The Alliance is being led by Argentina, the European Union, and Mongolia, but all countries that are committed to abolishing capital punishment under the UN Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights have been invited to participate.

Argentina’s commitment to ending the death penalty is unwavering. It is an active participant in multilateral institutions such as the International Commission and World Congress Against the Death Penalty, and it has been mobilising support within the UN for a global moratorium on executions.

The EU, meanwhile, tightened legislation last year to ban all trade in goods used for torture or capital punishment. The law, originally enacted in 2005, now bars all such goods from passing through EU territory and ports, and from being promoted at fairs and in industry publications. And to stay ahead of the curve, the EU has established a fast-track mechanism to ban new tools for torture or capital punishment as they emerge.

Mongolia, for its part, banned the death penalty in 2015, and is setting a positive example in a region where most countries systematically torture and execute prisoners.

Tougher controls have already delivered results. For example, the drugs used in forced lethal injections and devices for administering electrical shocks have become much harder to obtain and more expensive.

Still, there is a clear limit to what individual countries can achieve on their own. Those who produce and trade these goods are changing their practices and routes to circumvent domestic laws. Ultimately, to make policing efforts truly effective, more countries need to get on board.

When the Alliance launches this month, participating countries will sign a joint political declaration based on four commitments. First, they will implement measures to restrict the export of goods intended for torture or executions. Second, they will help to create a platform for exchanging information across borders, so that customs officials can monitor international trade flows and identify new products that should be interdicted.

Third, signatory countries will share their best practices, so that enforcement systems that have proven efficient and effective in one country can be adopted in others. And, fourth, those with national legislation already in place will provide technical assistance to other countries still working toward that end.

To be sure, rooting out torture and abolishing the death penalty will require broad, sustained efforts beyond the area of trade. But by focusing on the exchange of goods used for torture and executions, we are bringing like-minded countries together to effect real change. We are confident that the Alliance will be successful, and that it could serve as a basis for broader UN cooperation down the road.

Trade policies are not just about dollars and cents. They are also powerful tools for safeguarding human rights and supporting sustainable development around the world. We should never permit the tools of suffering and death to be traded like any other commodity.

(Jorge Faurie is Foreign Minister of Argentina. Cecilia Malmström is the European Union Commissioner for Trade. Tsend Munkh-Orgil is Foreign Minister of Mongolia.)