In March last year, the World Economic Forum (WEF) launched the fifth edition of their Energy Transition Index (ETI), ranking 115 economies on how well they are able to balance energy security and access with environmental sustainability and affordability. The report considered both, the current state of the countries’ energy systems as well as their readiness to adapt to future energy needs.

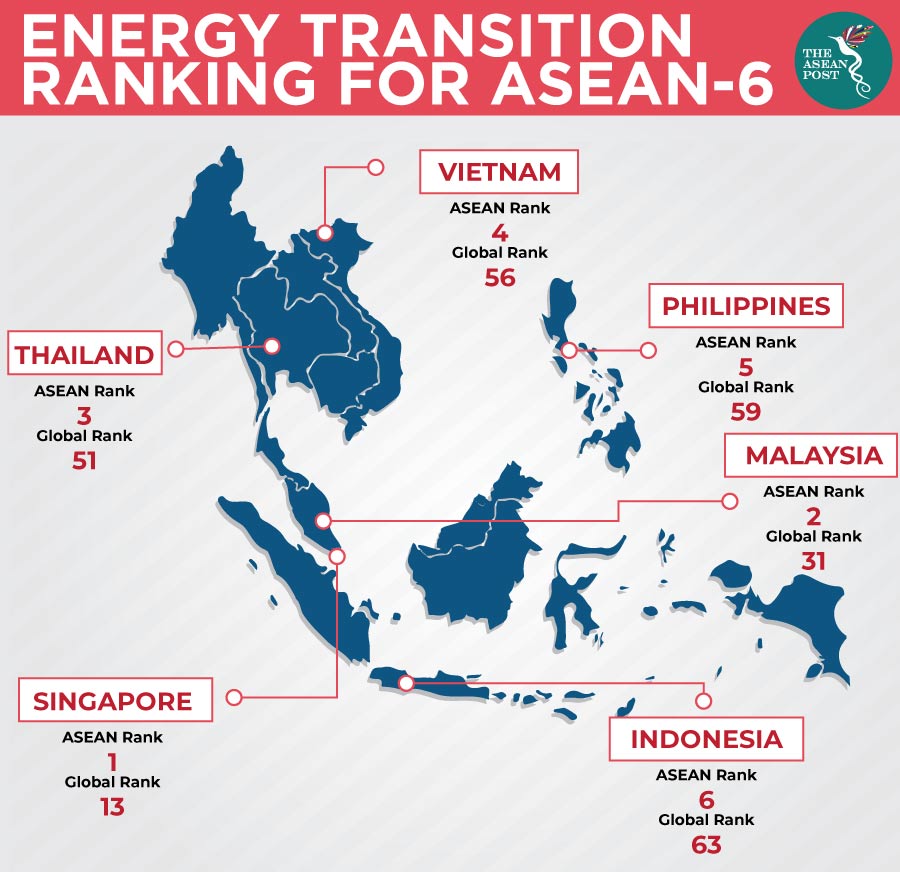

Six ASEAN countries came into focus based on their performance in the ETI: Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines.

In the case of Thailand, the country improved on all three dimensions of the energy triangle which is made up of security and access, environmental stability, and economic development and growth. Thailand also improved on transition readiness.

Despite being a net energy importer, Thailand scored high in the energy access and security dimension due to its well-diversified sources of energy. Its scores, however, are challenged by a combination of high wholesale gas prices and energy subsidies as a percentage of its gross domestic product (GDP).

Singapore – with an ETI ranking of 13 – is the highest-ranking country within the ASEAN region. It comes as no surprise that this is driven by high scores in ‘transition readiness’ which the WEF puts down to many years of stable policies, strong institutions, a strong governance framework and transparency along with a culture of innovation and modern infrastructure which enables the energy transition.

Unfortunately, for performance, Singapore scores lower due to the structural challenge of being a net energy importer with high concentration of fossil fuels (particularly gas) which impacts its performance across the energy access and security dimension. Dominance of fossil fuels has also impacted the dimension of environmental sustainability, where Singapore has high carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions on per capita basis and a very small share of renewables.

Malaysia brings home the prize for the highest-ranking country in the emerging and developing Asian region. Its energy access and security scores are also among the top 15 out of the 115 countries analysed in the ETI. This is the result of its high electrification rate, low usage of solid fuels, diversity of its fuel mix and high quality of electricity supply.

However, on the environmental front, both its carbon intensity and per capita carbon emissions are over 20 percent above the global average, giving the country a lower score for this dimension. Malaysia also scores high in transition readiness due to strong regulations and political commitment, a culture of innovation and high scores on the human capital front. Yet, its readiness for transition is challenged by the current energy system structure with high energy demand (on per capita basis) and the high share of coal in its electricity fuel mix.

Indonesia is heavily impacted by energy subsidies. On the environmental front, the country does relatively well with low energy intensity. Its energy access and security dimension, however, is reduced primarily due to relatively high solid fuel use by the population. As for readiness, the country’s key challenges are in coverage of energy efficiency policies, perception of rule of law, investment freedom and high share of coal in the power generation mix.

Vietnam scores low in the environmental sustainability dimension resulting from a high level of air pollutants, high energy intensity and a carbon-intensive energy system. On the energy access and security dimension, it is challenged due to the relatively high percentage of solid fuels used by the population. Vietnam’s energy transition challenges include relatively weaker institutions, a low level of investment freedom, and a low quality of transportation infrastructure.

In the Philippines, the WEF noted that the high prices of electricity there is driven by taxation and a Feed-in Tariff (FiT) structure that was used to incentivise renewables.

The good news is that the high penetration of renewables has balanced out the presence of large coal-based power generation and positively impacted the diversity of power supply in the country. Unfortunately, the country continues to face challenges in the energy access and security dimension due to the low quality of power supply, a relatively low electrification rate and high percentage of solid fuels usage.

On the transition readiness front, the Philippines has made ambitious nationally determined contributions (NDC) pledges despite having a low carbon footprint with 70 percent targeted reduction in CO2 by 2030. However, its readiness score is challenged by negative perceptions around institutions and governance, low scores in access to credit indicators, weak transportation infrastructure and a high share of coal in its power generation fleet.

As fossil fuels deplete and newer technologies emerge that cater to renewable energy sources, energy transition is an inevitability. The future of energy transition is an especially important area for ASEAN because urbanisation, industrialisation, and rising living standards continue to drive increases in energy demand. ASEAN, though still very much fossil-dependent, sees the importance of transitioning and is making an effort to do so.

Related articles: