In recent years, we have seen the renewal of a phenomenon that seemed to have passed into history with the end of the Cold War: fierce and potentially violent competition between the most powerful countries on the globe. Yet as dangerous as that competition is in its own right, it is also worsening prospects for solving many of the world’s other problems, from migration to economic crises to climate change.

Relations between the great powers - the United States (US) and its allies on the one hand, and revisionist authoritarian regimes such as China and Russia on the other - represent the new, volatile centre of gravity in world politics. When there is instability at the centre, it spreads outward and affects everything it touches.

Until relatively recently, many observers believed just the opposite: that all good things would go together in global affairs. One of the most widespread and optimistic notions of the 1990s and 2000s was the idea that the decline of traditional state-versus-state geopolitical conflict was making it easier to deal with the array of international and transnational challenges that threatened all of us. With American dominance unquestioned, and the major powers mostly getting along, the international community could focus greater attention on terrorism, climate change, pandemics, nuclear proliferation and other shared dangers. That cooperation, in turn, could reinforce the good feelings between the major powers.

This belief had bipartisan support. In 2002, the George W. Bush administration’s National Security Strategy held that the international community had an unprecedented opportunity to banish the geopolitical rivalries of the past by working to suppress the transnational dangers of the present. “Today, the world’s great powers find ourselves on the same side," that document noted, “united by common dangers of terrorist violence and chaos.”

During Barack Obama’s presidency, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton made the same argument. "Most nations worry about the same global threats," she explained. By inducing greater cooperation and reducing competition, Washington could make an emerging “multipolar world” into a “multi-partner world.”

This argument was always just true enough to be alluring. In the two decades after the Cold War, the US-led international community did achieve real cooperative success in grappling with a range of issues, from Saddam Hussein’s aggression in the Persian Gulf, to the brutal war in Bosnia in the mid-1990s, to piracy off the Horn of Africa, to the worldwide economic and financial crisis of 2008-09. In all of these areas, the historically low level of conflict between the major powers was critical to getting things done.

Yet the imperative of working together on these challenges was not strong enough to overcome the impetus toward renewed competition as China and Russia gradually gained the ability to reassert themselves. And as geopolitical tensions have flared over the last decade, the prospects for positive-sum collaboration have dimmed.

Consider the ongoing civil war in Syria. For nearly eight years, frictions between the US and Russia (as well as Russia’s ally in that conflict, Iran) have consistently stymied greater international pressure on the Bashar al-Assad regime to hand over power or simply stop the killing. At every step, Moscow protected Assad and helped him keep waging war against his own population rather than seeing a Russian partner in the Middle East toppled by a US-backed revolt. If successful international intervention, blessed by the United Nations (UN) Security Council, in Bosnia in 1995-96 was a symbol of the mutually reinforcing relationship between great-power comity and global cooperation, the nightmare in Assad’s Syria stands as a marker of the perverse symbiosis between great-power conflict and global disorder.

The global deadlock on migration offers another example. For many countries in Europe, migration - particularly refugee flows - is not simply a humanitarian crisis but a threat to political and social stability. For Putin’s Russia, however, those same refugee flows are a useful tool for weakening Europe and stoking the fires of illiberal populism within the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU). Look no further for the reason Russia has often fought its war in Syria in ways that seem calculated to maximize the displacement of civilians.

All this would be bad enough if the zero-sum logic of strategic competition were making its impact felt only in these areas. But there is a strong possibility that it will weaken the possibilities for progress on even more important matters.

Geopolitics and geo-economics can never be separated from each other, and the next time there is a global economic crisis the major powers will have significant incentives to respond in ways that prioritise unilateral advantage over multilateral collaboration. In the 1930s, surging tensions in Europe and East Asia made it impossible to find coordinated solutions to the Great Depression, leading instead to beggar-thy-neighbour policies that worsened the economic carnage. And in 2008, Russia reportedly sought to crater America’s economy by proposing to China that the two countries jointly dump their bonds in the US-government-backed lenders Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. As US-Russia and especially US-China relations continue to deteriorate, the chances of effective global crisis-management will only become weaker.

One even wonders whether the politics of climate change will be affected. The recent report of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is alarming: It makes clear that drastic global action will soon be necessary to stave off a catastrophic rise in temperatures. Yet climate change diplomacy has always been complicated by calculations of national advantage and fears that limiting greenhouse emissions will disproportionately affect one’s own economic power.

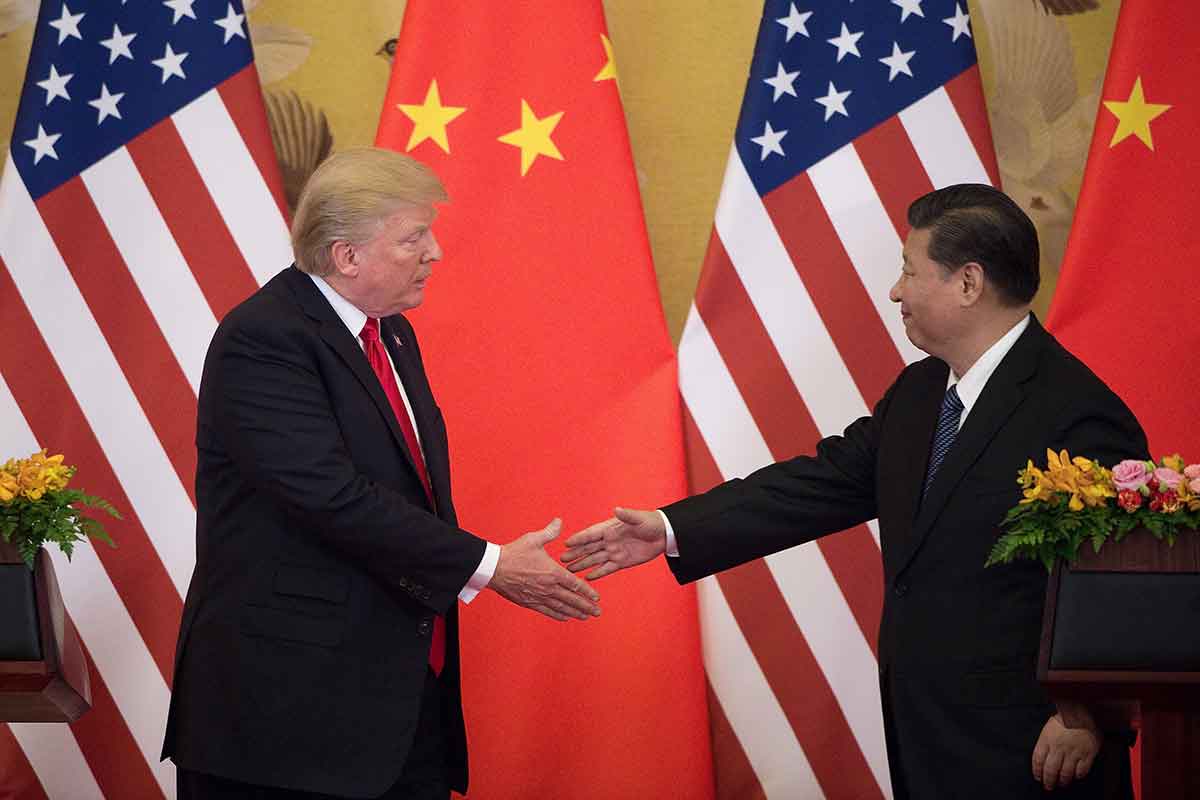

Now the Trump administration is taking those calculations to an extreme by announcing its intent to pull out of the Paris climate change accords on grounds that honouring America’s commitments will undermine its global competitiveness. (Whether this is actually the case is sharply disputed by critics of the administration’s decision.) Meanwhile, the relationship that must be at the centre of any meaningful climate change agreement - that between the US and China - is worsening by the day.

Perhaps the truly dire consequences of not tackling climate change will prevent the US (under a future president) and its rivals from forsaking cooperation on this issue. After all, the unimaginable consequences of nuclear holocaust created the basis for superpower cooperation on arms control during the Cold War.

But at the very least, achieving that cooperation will require resisting the growing pressures generated by geopolitical strife. Even in the best of circumstances, it is hard enough for governments to solve problems that cross international borders. In a time of sharp strategic rivalry, it is going to get much harder. - Bloomberg