The Southeast Asian region has had its fair share of natural disasters over the years. In terms of sheer destruction, the most devastating of these was the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami of 2004.

While the impact of that disaster was felt regionwide, Indonesia was the hardest hit among ASEAN member states, with more than 130,000 people dead and extensive infrastructural damage. Malaysia, Myanmar and Thailand were affected as well, albeit on smaller scales when compared to the loss of life in Banda Aceh.

Aside from natural disasters, man-made tragedies are a major concern within the region as well, exemplified by the atrocities perpetrated against the Rohingya peoples in the Rakhine State of Myanmar. To address crises like these, the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on Disaster Management (AHA Centre) was formed to ease the plight of victims of both, natural and man-made disasters in the region.

Source: The AHA Centre

Regionwide collaboration

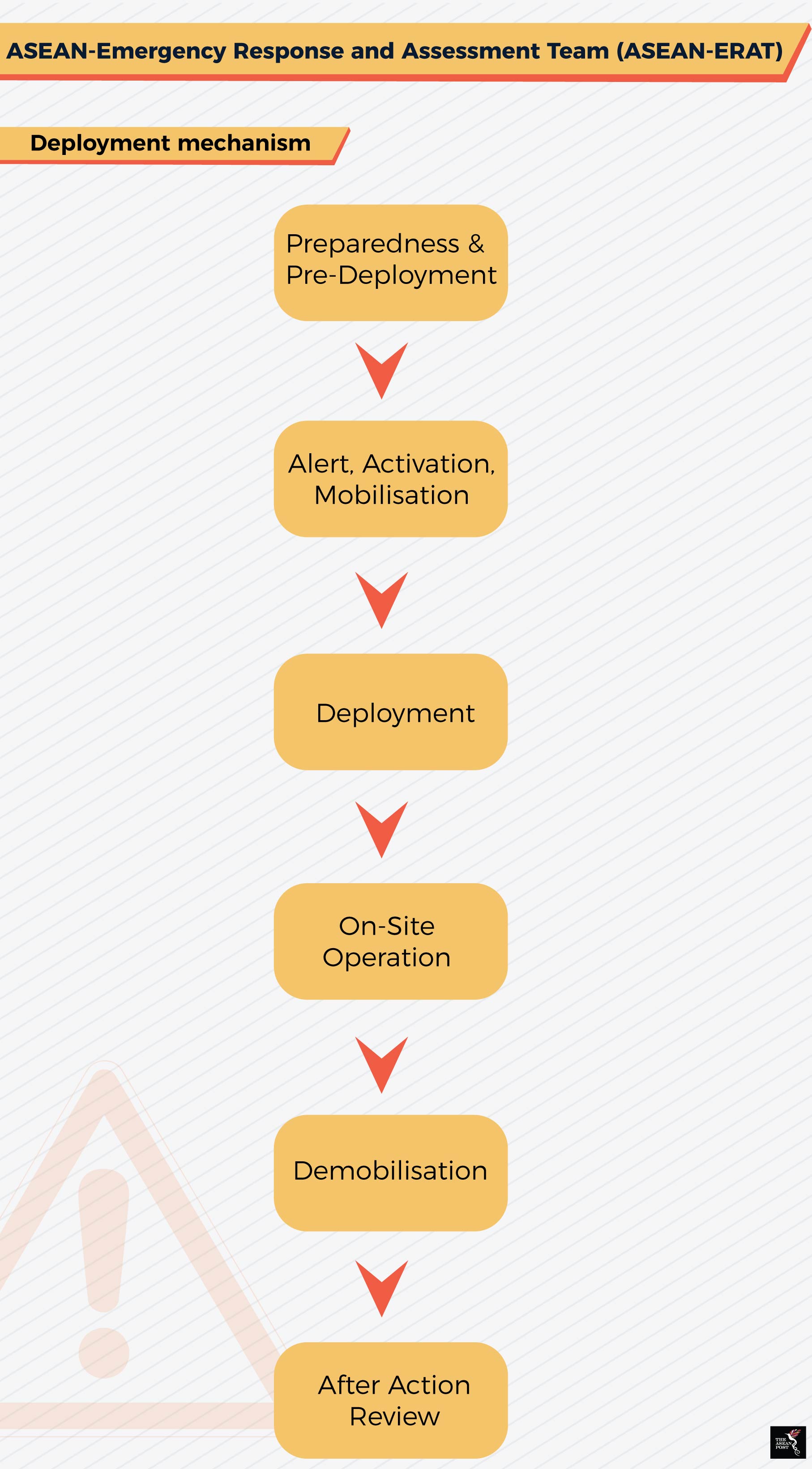

Established on 17 November 2011, the AHA Centre aims to facilitate cooperation and coordination among ASEAN member states with the United Nations and other international entities for disaster management and emergency response in the region. According to the AHA Centre, disasters in Southeast Asia account for more than 50 percent of all fatalities resulting from disasters worldwide during the past decade. A total of 354,000 out of the 700,000 deaths took place in the region. Moreover, these disasters have also led to financial losses amounting to US$91 billion.

Against this unfortunate backdrop, collective multi-stakeholder partnerships are urgently required to not only improve upon the region’s ability to cope with disasters when they occur but to also reduce their likelihood in the region.

In order to carry out its work effectively, the AHA Centre coordinates its activities with National Disaster Management Organisations (NDMOs) in Southeast Asian countries. Furthermore, the AHA Centre also partners with international organisations, the private sector, and civil society organisations such as the Red Cross, Red Crescent and the United Nations.

The formation of the AHA Centre is in line with the ASEAN Vision 2025 on Disaster Management. Its role is to be a network coordinator for regional centres for excellence in disaster management and emergency response. This particular vision has three areas of focus; institutionalisation and communications, partnerships and innovation, and finance and resource mobilisations.

Source: The AHA Centre

The AHA Centre’s breadth, depth, and possible limitations

Budgetary constraints have limited ASEAN’s regional operations. An example of this was when Cyclone Nargis hit Myanmar in 2008. In dealing with the worst natural disaster in the country’s history, funding for ASEAN’s engagement did not come from its member states but was mostly derived from international donors, along with some contributions from private foundations.

Staffing limitations also have to be borne in mind when considering the scope of ASEAN’s humanitarian capacity. ASEAN’s shortcomings become more evident when it comes to man-made crises. The association’s belief in the principles of non-interference limits its humanitarian mandate for disasters, which has drawn the ire of many from outside the region, in light of what is happening in the Rakhine state.

When compared to the Organisation of American States (OAS) for example, ASEAN lacks a strong mechanism for the enforcement of human rights. Thus, it is not erroneous to point out that ASEAN still lags behind other regional blocs in terms of conflict resolution.

In light of such pressing concerns, it is imperative that a technical information-sharing system with operational resources and support from ASEAN governments be put in place through the AHA Centre. Fast tracking of access for humanitarian missions to disaster areas is also a priority.

ASEAN could play a pivotal role in facilitating negotiations on aid access, including visas for aid workers and easier customs clearances for aid materials, both prior to a crisis and in response to one. ASEAN should also begin discussions on increasing contributions to the AHA Centre and developing a comprehensive timeframe for it to become self-financed.

On the whole, the AHA Centre has experienced momentum changes, surges, and shifts in stability that go hand-in-hand with partnership development. Despite this, it remains a much-needed regional institution when dealing with man-made or natural disasters in Southeast Asia.