The European Union (EU) recently told Cambodia that the Kingdom will lose its special access to the world's largest trading bloc, saying that it was ready to punish human rights abuses in the country. The EU warned that it has launched a six-month review of Cambodia's duty-free access to the EU; meaning garments, sugar and other exports could face tariffs within the next 12 months. Around 40 percent of Cambodia’s gross domestic product (GDP) comes from garment exports, making it vital to its economy. However, Cambodia's Prime Minister Hun Sen’s stance has remained one of defiance.

Observers have pointed to the United States (US)-China trade war as the reason for Hun Sen’s apparent lack of concern. In 2017, despite numerous human rights violations having allegedly been committed under Hun Sen’s rule, investments from Beijing still came pouring in. Towards the end of the year, Chinese firms had pledged to invest US$7 billion in development projects, including an expressway connecting the capital, Phnom Penh and the coastal port city of Sihanoukville, a satellite city just outside the capital, a tourism centre and the launching of a commercial bank.

The US, on the other hand, had at least made attempts to hold Cambodia responsible. Days before Cambodia’s general election on 29 July, the US House of Representatives passed The Cambodia Democracy Act of 2018 which would allow Washington to impose sanctions on Hun Sen and members of his inner circle. The US Senate has yet to pass this Act and Cambodia has predictably shrugged it off.

Just fine without the EU

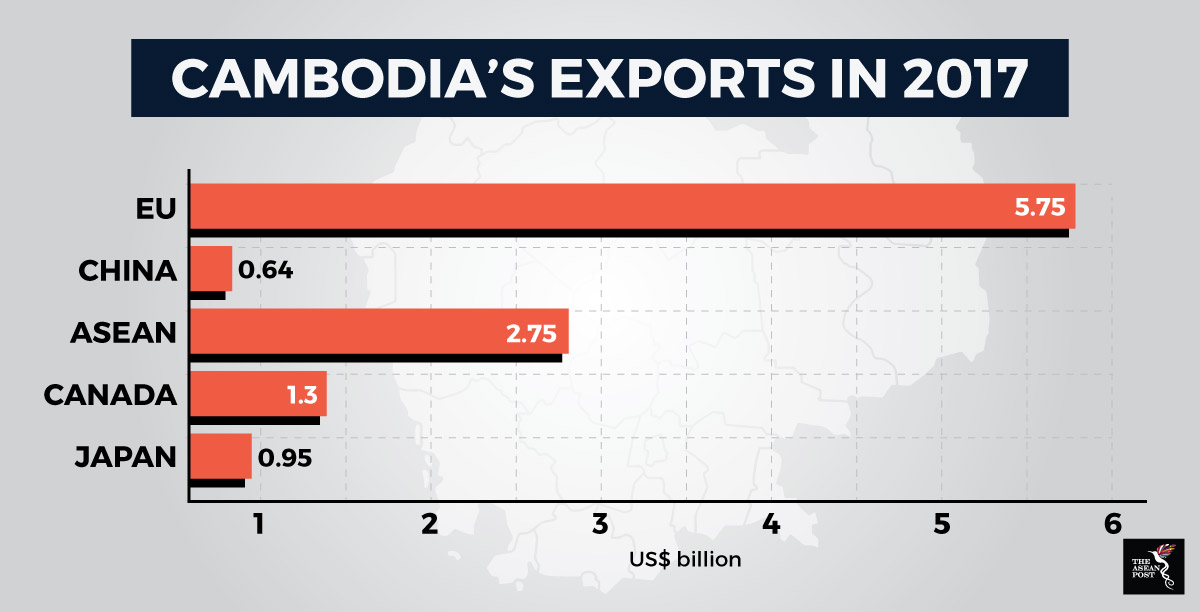

Despite the EU promising repercussions, Cambodia remains unfazed. This is worrying considering that in 2017, according to the European Commission (EC), the EU imported US$5.7 billion worth of goods from Cambodia. So, what is Hun Sen thinking?

For one, Cambodia has seen significant growth in exports to Japan. Figures from the Japanese External Trade Organization (JETRO) in August revealed that the Kingdom sent goods worth more than US$700 million to the island nation during the first six months of this year, marking a growth of 19 percent over the same period in 2017. During the first half of last year, Cambodian exports to Japan grew by 4.5 percent, rising to 4.6 percent for the entire year. It marked the first time since the financial crisis of 2008 that growth stayed in single digits.

Reports in January revealed that Cambodia’s exports to China rose sharply during the first 11 months of 2017, by as much as 18 percent compared with the same period in 2016, according to the latest data from Cambodia’s Ministry of Commerce. Total exports to the Chinese market reached US$634 million from January to November 2017, an 18 percent increase. As the trade war goes on, it’s likely China will continue pumping money into the ASEAN region, Cambodia included.

But it isn’t just Japan and China that Cambodia is looking to trade with. According to Canada’s official statistics, as much as US$1.3 billion worth of goods was imported from Cambodia in 2017. Canada has also remained mostly silent regarding the allegations of human rights violations in the ASEAN country.

Cambodia’s status as an ASEAN member also ensures that it will have guaranteed trade partners. Reports show that Cambodian exports to ASEAN member countries in 2017 amounted to US$2.7 billion; the main importers being Singapore (US$1.3 billion) and Thailand (US$1 billion). In February, Thailand’s minister counsellor (commercial) at the Commerce Ministry, Jirawuth Suwanna-Aat said Thailand and Cambodia were working towards the goal of having trade flows between the two neighbours growing to US$15 billion in 2020.

Source: Various sources

Japan isn’t going anywhere

While Japan may be one of the US’ strongest allies, it is unlikely that it will decide to give Cambodia the cold shoulder even if the US disapproves. During the recent 10th Mekong-Japan Summit Meeting on 9 October, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe promised to offer up to US$31.6 million in low-interest loans to repair and build irrigation facilities around the Tonle Sap Lake. The move marks the 65th anniversary since Japan and Cambodia established diplomatic ties.

Two days prior, Cambodian residents in Japan gathered in the capital's Shinjuku Ward to protest Hun Sen’s visit. The Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) estimated some 600 people gathered for the demonstration organized by the Japanese branch of the Cambodia National Rescue Movement (CNRM), an internationally based successor to the dissolved Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP).

Japan addressed the matter when Abe said the country will invite young politicians from various parties and senior officials of the national election board in Cambodia to learn about Japanese election systems so they could further develop democratic processes. However, allegations of a false democracy in Cambodia has not stopped the Japanese yen from rolling into the Kingdom’s coffers.

Hun Sen’s response was to say that he was “very satisfied” with Abe’s proposals, adding that they will contribute to the development of democracy in his country. Meanwhile, in an interview with Japanese news agency Kyodo, Hun Sen reportedly said his eldest son Hun Manet could be a “possible future leader” of Cambodia.

Cambodia isn’t the only country that has managed to escape censure for alleged human rights violations. In a recent article, The ASEAN Post explored how the same situation is unfolding in Myanmar. Unfortunately, it seems that as long as the US-China trade war continues and China is ever-willing to overlook human rights violations, it will be the citizenry of ASEAN who will suffer.

Related articles:

How trade wars affect human rights

Backed by China, Hun Sen remains unstoppable