Commercial fishing is a matter of national security. It is a source of employment and income for thousands of fishermen in Southeast Asia. The lucrative industry is also a large contributor to the gross domestic product (GDP) of many ASEAN nations.

The extraction of this natural resource has been the cause of many international spats in recent history. Nowhere is this more prevalent than in the South China Sea. The area is biologically diverse and is home to 3,365 species of fish. It is also one of the top five most productive fishing zones in the world with regard to total annual marine production. It helps the coastal economy and is a crucial element of the export trade and food security in the 12 countries and territories it borders.

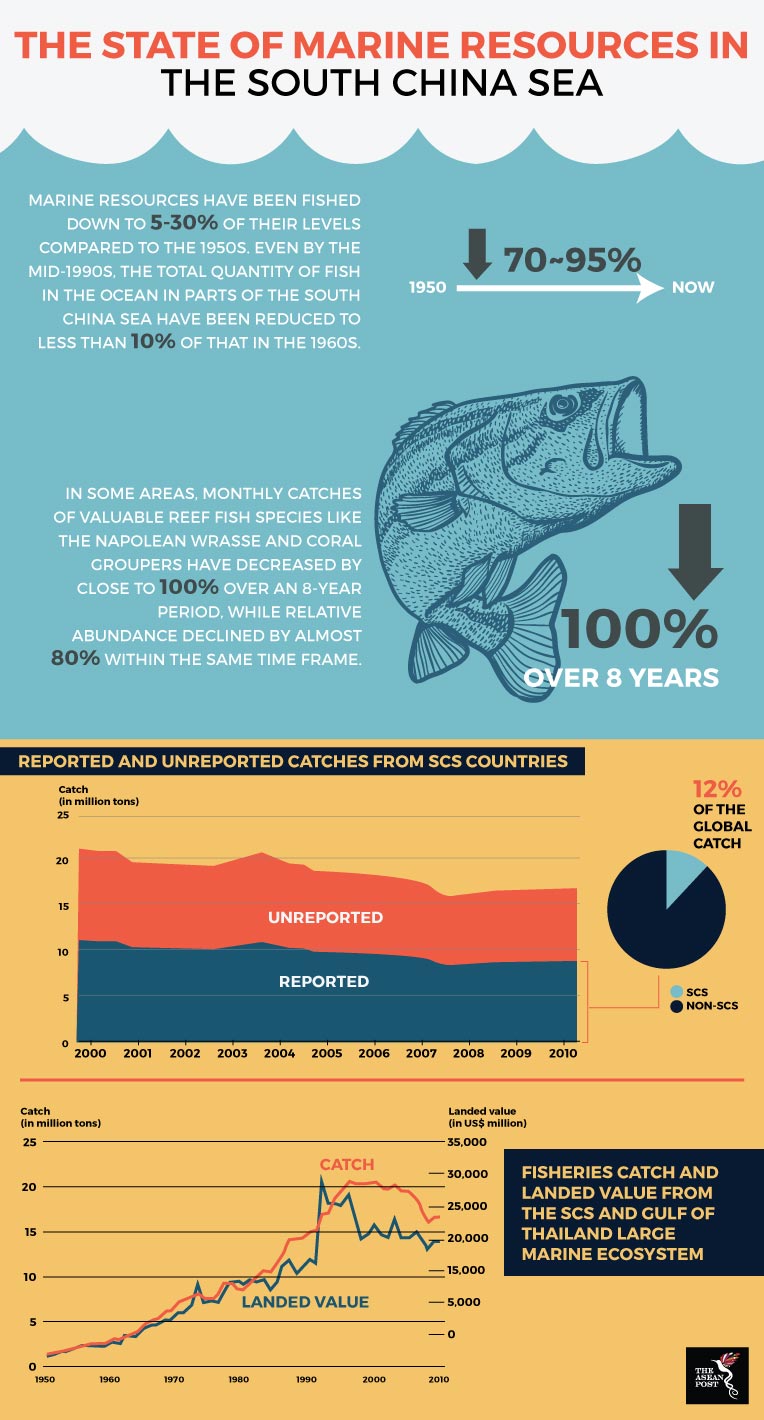

The maritime disputes and standoffs accompanying claims of national sovereignty are only one facet of the problem. 12 percent of the global fish catch comes from the South China Sea, hence, whoever has control over this area, would have access to an immense resource of saltwater fish.

The fish resources of the South China Sea are a global common. This makes it incredibly difficult to properly police the rate of resource extraction.

Deteriorating numbers

It is overfishing which ultimately causes fisheries to dwindle in numbers. Conservative estimates indicate that marine resources have been fished down to 30 percent of their levels compared to the 1950s. However, a more pessimistic outlook puts that number at five percent - meaning that more than 95 percent of the total fish mass has been extracted since the 1950s.

Kee Alfian, a marine biologist with environment consultancy firm, SEAlutions, told The ASEAN Post that continuous overfishing will ultimately lead to the collapse of the marine ecosystem in the South China Sea.

“The delicate balance between prey-predator is important to keep the ecosystem stable,” he said.

“The herbivores feed on the algae and the big fish feed on herbivore fish which are mostly small. When all the big prey is removed, it will disrupt the population size balance and overpopulation of certain species which will bring destruction to the ecosystem,” he explained.

The use of explosives for “dynamite fishing” and cyanide has had a devastating impact on coral reefs. Multiple studies have shown that coral reefs in the South China Sea are decreasing at an alarming rate of almost 16 percent per decade which has negatively impacted its biodiversity.

Southeast Asia’s consumers are already starting to feel the effects of overfishing in their lives in the form of higher prices for most varieties of seafood at local markets throughout the region.

Source: OceanAsia Project

Solution at hand?

The obvious solution is to place controls on fishing in order to sustain fish stocks for the longer term. These resources are inherently renewable, however, in order for it to stay that way, it must be given time. This is where the complexities of maritime boundary issues in disputed areas of the South China Sea come into play.

China, sees itself as “big brother” when it comes to policing this valuable natural resource. But this has not come about without protest. A few months back, Vietnam objected to a temporary Chinese ban on fishing in order to repopulate fish stocks. The controversy was due to the fact that China’s ban covered areas supposedly under Vietnamese sovereignty. This is just one of many similar fishing related incidences which have led to a strain in relations between countries bordering the South China Sea.

Cases of fishermen from one country straying into the waters of another and being reprimanded by the coastal officers there have also received widespread coverage in the media. No matter what the story is, the underlying issue is always the same: who decides which party is in the right?

The idealist answer is to call for an international maritime resource sharing initiative. Such levels of cooperation have proven successful in the European and Nordic regions where fishing is a vital part of the economy. But such endeavours are difficult to achieve in this region given prevailing “fishing nationalism” sentiments which have been rife.

Solving collective action issues like these are not possible without intensive academic research. The conundrum famously articulated in Garret Hardin’s “The Tragedy of the Commons” perhaps found its most reliable solution in the works of Nobel laureate, Elinor Ostrom. Ostrom advocated for community mobilisation in solving collective action problems – especially in situations where no central authority exists to determine private allocation of the resource.

However, a tricky dimension to this issue is that the groups that engage in fishing within the South China Sea aren’t from a single country. In fact, the very problem lies in that there are competing national claims of sovereignty which groups of fishermen use as a basis to assert their right to fish in a particular area. Hence, the problem must be tackled in a twofold manner. Not only must there be government-to-government engagement to handle the nitty gritty of international borders, but other relevant stakeholders (i.e. fishermen and the wider fishing community) must participate in these discussions as well.

Ultimately, the mix of state and group governance should lead to more emphasis being given to the latter. After all, such groups are able to better utilise local knowledge in governing the commons – in this case fish stocks – and hopefully develop a mechanism to naturally monitor one another.

Commercialisation – the real devil

Alfian puts forward an alternative viewpoint that overfishing and the South China Sea dispute should not be tied. Instead, he pinned the reason for overfishing on commercialisation and greed wherein demand is too high and supply is never enough.

“So, the net becomes bigger and bigger and frequency of operations becomes too frequent,” he said.

“By-catch (the unwanted fish and other marine creatures trapped by commercial fishing nets during fishing for a different species) is becoming a problem too,” he added. Often times these catches would be discarded or turned into trash fish.

“Big trawlers don’t discriminate, and the operation is very disruptive to the ecosystem,” Alfian remarked. “I say ecosystem and not environment because by removing one species, its effects can be felt across the food chain, not only the environment, where it may only affect certain specific areas.”

“Ultimately, coastal or local fishing communities are not the problem or the culprits,” Alfian concluded.

“It’s the big player, those big trawling companies whose operations cost millions! They are the ones who need to be regulated strictly.”