In 2015, the world’s leaders came together to pledge the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The 2030 Agenda is a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure all people enjoy peace and prosperity through global partnership. Built on the achievements of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for 2000-2015, it is monitored against a set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These SDGs target achievements in poverty and hunger eradication, health and wellbeing, education, gender and economic inequalities, conservation, climate change, innovation, sustainable consumption, and peace and justice.

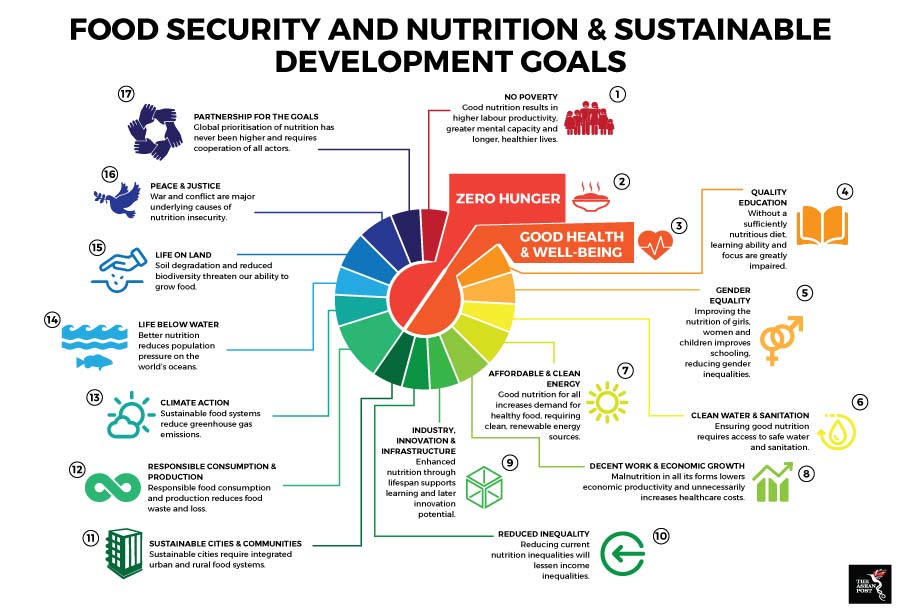

One of the key features of the SDGs is the interconnectedness of the goals. No one goal can be fully achieved without progress in the others, and efforts towards achieving one goal almost always will impact the progress of others. The failure to plan for one SDG may also decelerate or render ineffective planning and implementation of national initiatives for other goals.

Food security, for example, underpins the achievements of all other SDGs. Primarily, it is targeted under SDG 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture. In turn, the fulfilment of a population’s food, energy, and nutritional needs, as well as advancements in sustainable agriculture, provide for conducive conditions to improve health, mental and labour capacity, sustainability of cities and urbanisation. This further strengthen efforts towards industry building, levelling the playing field for poorer communities, women’s participation in work and society, responsible consumption and production, and reducing conflicts. At the same time, the attainment of SDG 2 depends largely and impacts absolutely on the achievements in clean water and sanitation, affordable and clean energy, climate action, life on land, and life below water.

An example of the interlinkages between food insecurity and the different SDGs can be seen in Lao PDR. According to Lao PDR’s Voluntary National Review of the 2030 Agenda, around 33 percent of children under five in the country were reported to be stunted and nine percent wasted in 2016/17. Stunting is a manifestation of chronic or long-term hunger, while wasting is a manifestation of acute hunger such as those experienced during a famine or crises. In Lao PDR, these manifestations show a strong influence of inequalities associated with poverty and ethnicity, as well as rural-urban disparity.

Stunting in rural areas without road access is twice that in urban areas. Stunting in children from some highland ethnic groups is nearly double that of children from lowland groups. Stunting amongst children from the poorest households are three times higher than those from the richest households. Stunting amongst children of uneducated women are four times higher than children of mothers with at least a secondary education. All these manifestations prove strong and direct interconnectedness between SDG 2 and other SDGs on poverty, education, income inequalities, gender, sustainable communities, infrastructure, partnership, and more.

More needs to be done

Having previously achieved its MDG target of halving the proportion of undernourished or hungry people – from 42.8 percent in 1990 to around 18.5 percent in 2015 – Lao PDR now is committed to reducing the high prevalence of underweight and stunting amongst its children. This is demonstrated through its National Zero Hunger Challenge launched in May 2015, as well as the Agricultural Development Strategy, National Nutrition Strategy, and the National Socio-Economic Development Plan.

Lao PDR authorities last week set a target to increase farmland in 2018-2019 from 177,000 hectares to 185,000 hectares. In another effort to ensure food security and commercial farm production, the Japanese government will be providing another grant to the Lao government for improvement of the Irrigation Agriculture Project at Tha Ngon farmland in Xaythany district, Vientiane, in a project expected to start this month.

While handling the current drivers of hunger, ASEAN countries also need to keep an eye on changes to the climate. ‘The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018’ report published by the United Nations (UN) Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) last year reported an increase in the prevalence of severely food insecure people in the region, increasing from 7.3 percent or 46 million people to 10.1 percent or 65.8 million people between 2014 and 2017. The trend, observed in three consecutive years, is largely driven by the adverse effects of climate conditions on food availability and prices.

The derailment of efforts to achieve Zero Hunger can and will have adverse impacts on national aspirations and development trajectories. At different levels of development, ASEAN countries need to not only look at specific challenges facing their respective nations, but also come together to learn from each other’s experiences. Just as how all SDGs are interconnected, ASEAN’s success in attaining all SDG goals too is dependent on how effectively member states work together towards common goals.

This article was first published by The ASEAN Post on 15 September 2018 and has been updated to reflect the latest data.

Related articles:

Water stress giving renewables a bad name