Early this year, researchers urged conservationists and palm oil companies tackling deforestation and forest fires to rely less on satellite imagery and to start “listening” to the sounds of the forest instead. In a report published by the journal Science on 4 January, researchers said the use of “bioacoustics” to record, monitor and log background sounds – like animals, insects and human activity – provides crucial data needed for more effective conservation.

"You can look at a primary forest, map the soundscapes to see what is normal and then do the same at a logging concession, plantation or hunting area. With a camera trap, you're at risk of a hunter or poacher coming in and destroying it. But audio equipment you can mount up to 30 metres up a tree and nobody will see them," said co-author Rhett Butler.

At the moment, most conservation efforts and studies rely on sample data from an area or satellite imagery that only shows forest cover, does not pick up selective logging, and may have problems with cloud cover, Butler added.

He pointed out that relatively cheap audio equipment can be used to record and monitor subtle changes to wildlife or send alerts when gunshots, vehicles or chainsaw sounds are logged.

The sounds of human voices or fire in a forested area could also alert and pinpoint an at-risk area to help Indonesia tackle its annual forest fires, Butler said.

The paper also recommended the creation of a global organisation to host an acoustic platform that produces on-the-fly analysis from the data collected using bioacoustics. Not only could the data be used for academic research, but it could monitor conservation policies and strategies employed by companies around the world, the authors added.

What satellite imagery says

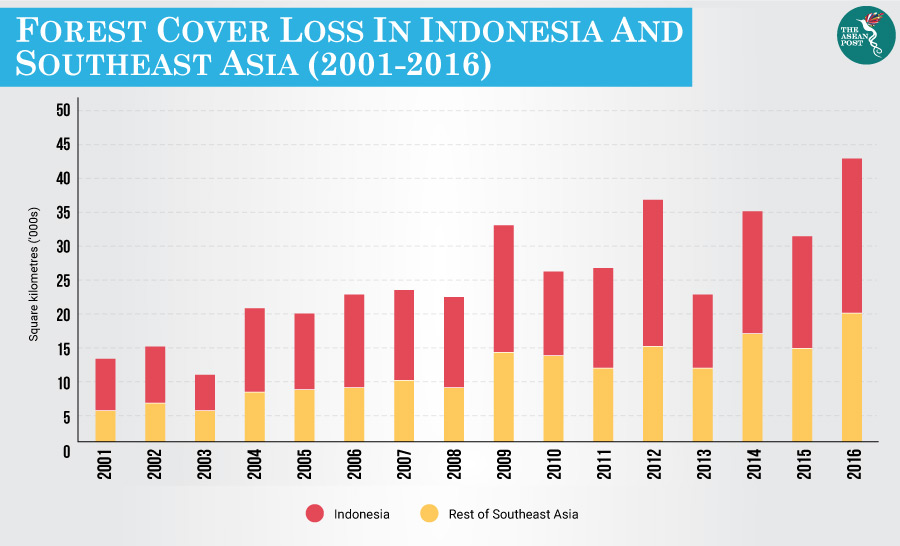

In October last year, a joint study carried out by the University of Maryland (UM), Google, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) under the Global Forest Watch (GFW) had found that more than 227,000 square kilometres of forest cover had been lost between 2001 and 2016. While deforestation and degradation of forested land are major issues for the region, the condition in one country in particular, Indonesia, is alarming.

The forest cover lost in the region was largely driven by demand for natural resources and land clearing for producing food and other commodities. In Indonesia, specifically, the main driver for deforestation is the practice of slash-and-burn to establish palm oil plantations. The practice is a major contributor to the transboundary haze issue that is impacting millions of people in the region, mostly in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. This is further enabled by poor enforcement and weak governance.

Real-time forest management and deforestation monitoring are generally challenged by inaccurate, incomplete and outdated information. When data is available, such as in the case of NASA satellite imagery, it is not at a resolution or consistency that is sufficient for enforcement. Hardware that is crucial to processing and viewing the data is also beyond the reach of developing nations, advocacy organisations and other groups that need it the most.

Through the collaboration of Google, UM, USGS and NASA, GFW has released a global forest map, the largest catalogue for earth observation data, updated at near-real time. Akin to the human genome project but based on the earth’s ecosystems, GFW’s map boasts fine enough resolution to detect even small-holder agricultural activities. It provides data and tools for monitoring forests for free to non-profit organisations, as well as forest management and law enforcement agencies in tropical countries.

Reducing forest fires

While the situation in Indonesia is far from pretty, the government there has not tried to brush the issue aside. In January 2018, it expressed confidence that it could halve the number of forest fires in the country by 2019 after unveiling an ambitious plan. This, it said, would be done through the repair of degraded peat forests.

Indonesia said it aims to tackle fires via two crucial steps. The first step includes ensuring that the 24,000 square kilometres that is slated to be restored by Indonesia’s peatland restoration agency will not be burned. The second step incorporates stepping up prevention efforts in 731 villages in Sumatra and Kalimantan which are the two parts most prone to fires.

The situation, however, does not seem to have improved. Merely a month after expressing its confidence in tackling the matter, Indonesia saw the return of its infamous annual forest fires producing toxic, choking smog in the form of haze.

If Indonesia is serious about tackling deforestation and reducing forest fires, then perhaps it should do as Butler suggests and start “listening” to the forest.

Related articles: