Last month, the United Nations Committee for Development Policy announced that Lao PDR had fulfilled the criteria to graduate from Least Developed Country (LDC) status for the first time. The Indochinese nation’s per capita Gross National Income (GNI) of US$ 1,996 exceeded the graduation threshold of US$ 1,230 or above. Besides that, Lao PDR scored 72.8, more than the 66 or above rating on the Human Assets Index. The country’s Economic Vulnerability Index also reached 33.7, fairly close to the limit of 32 or below.

In short, Lao PDR is on the precipice of astounding economic growth. Estimates by the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Asian Development Bank (ADB), put the forecast economic growth figures for this year at upwards of 7 percent. To sustain this economic growth, Lao PDR needs sufficient energy supply, especially for electricity generation, in order to power the gears of industrial development.

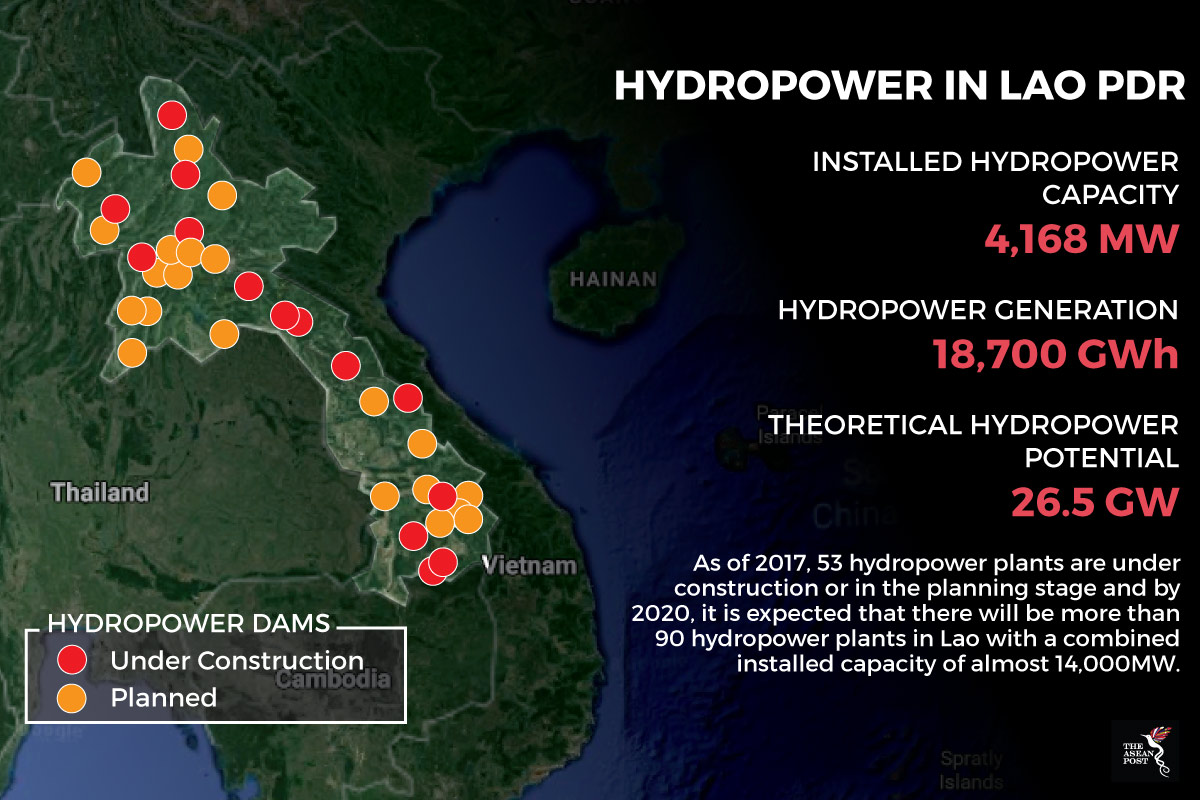

Lao PDR is a country which lies almost entirely in the lower Mekong basin and is not short of access to hydropower energy. Hydropower has always been an important symbol to the nation of Lao PDR, so much so that it even appears on Laotian banknotes. According to the International Hydropower Association, Lao PDR’s theoretical hydropower potential is 26.5 gigawatts (GW). As of 2016, the country has an installed capacity of 4.17 GW, leaving a gap of 22.3 GW in unrealised potential.

Realistically, not all of this potential can be harnessed. Since Laotian households enjoy one of the highest grid quality electrification rates in Southeast Asia, this begs an important question. How can these latent prospects be put to better use?

There is no definite answer to this. After all, there is still work to be done to ensure much of the rural areas in Lao PDR are electrified. Besides that, Lao PDR could also benefit from increasing its ready supply of electricity to industrial areas which could promote the development of heavy industries in the country.

One area which could benefit Lao domestically as well as regionally, is the cross-border sale of electricity. Within Southeast Asia, such plans are rather nascent and are only recently gaining popularity with 12 interconnection projects either planned or already in the works. Thanks to Lao PDR’s immense untapped potential, it has an incredible opportunity to harness this energy and fulfil its epithet as Southeast Asia’s “battery”.

Currently, Lao PDR exports 67 percent of all its hydropower generated electricity, accounting for almost 30 percent of its total exports. Its main customers are neighbouring Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia. Thailand signed a power purchase scheme outlining an agreement for Lao PDR to supply the Land of Smiles with 7,000 MW of power by 2020. This comes on the heels of rapid development in Thailand which has increased the demand for electricity.

Similar economic conditions have also resulted in Vietnam and Cambodia inking bilateral deals with Vientiane to supply them with 5,000 MW and 200 MW, respectively. To protect the domestic electricity market, Lao PDR’s laws require independent power producers (IPP) that export energy to maintain a 10 percent reserve of their total installed capacity for domestic use.

The forecasted overall increase in electricity demand within the region in the coming years means that Lao PDR could very well position itself as a key supplier of electricity within the Indochinese, and possibly, wider ASEAN region. Hence, it could be a leader in realising the ambitions of the ASEAN Power Grid, an initiative which aims to construct a region-wide power interconnection network.

The sore thumb that sticks out for Lao PDR though is the environmental implications of sustained hydropower development. For example, the government’s flagship, Nam Theun 2, 1,070 MW dam has been touted by many environmentalists as a “failed investment” because of the dam’s detrimental effects on the environment.

“Some of the impacts of Nam Theun 2 include a dramatic drop in wild fish catches, flooding of low-lying rice fields, inundation of riverbank gardens used for food cultivation, and recurring skin rashes from the now turbid river water,” explained Tanya Lee, Lao PDR Program Coordinator for International Rivers.

Sustainable and environmentally friendly methods of harnessing hydropower are being actively developed, the world over. Lao PDR will have to shake off the bad connotations of hydropower by embracing these newer methods. In the long run, hydroelectricity can serve as the strong backbone of the economy. The trick here is for Lao PDR to match economic gain with environmental goals as well.