Environmental issues like climate change and greenhouse gas emissions have come to shape the global agenda for the future. The logic it follows is simple – no environment, no humanity.

This concern was most urgently dealt with on a cold winters’ day in December 2015 in Paris when the leaders of 195 countries agreed to adopt the world’s first ever universal global climate deal. The Paris agreement aimed to counteract the threat of global climate change by ensuring global temperature rise was limited to below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels – maybe even by 1.5 degrees Celsius in the best-case scenario.

Are these goals ambitious? Yes, and optimists were quick to point out that in order to reach this goal, there must be strong environmental leadership backing the efforts from start to finish. No points for guessing which country slides into that position by default – it is the United States of America (US).

However, the US’ role as global leader in this initiative came to an unceremonious end after the election of Donald Trump as president and the subsequent withdrawal from the climate deal. Trump’s argument was that the deal will hurt American businesses and workers which doesn’t square with his America First policy.

The jury is still out on whether this is the case or not. Besides that, in accordance to Article 28 of the agreement, the US can only effectively withdraw from the deal in November 2020 but Trump’s words created a leadership vacuum in terms of global environmental leadership. Waiting to fill that position, is China and for good reason.

The environment is a public good, shared by all of humanity and the US has played the role as a global leader in setting the environmental agenda and leading key efforts towards sustainable development. Under current developments, China would not miss a chance at setting the climate agenda and establishing dominance in this conversation.

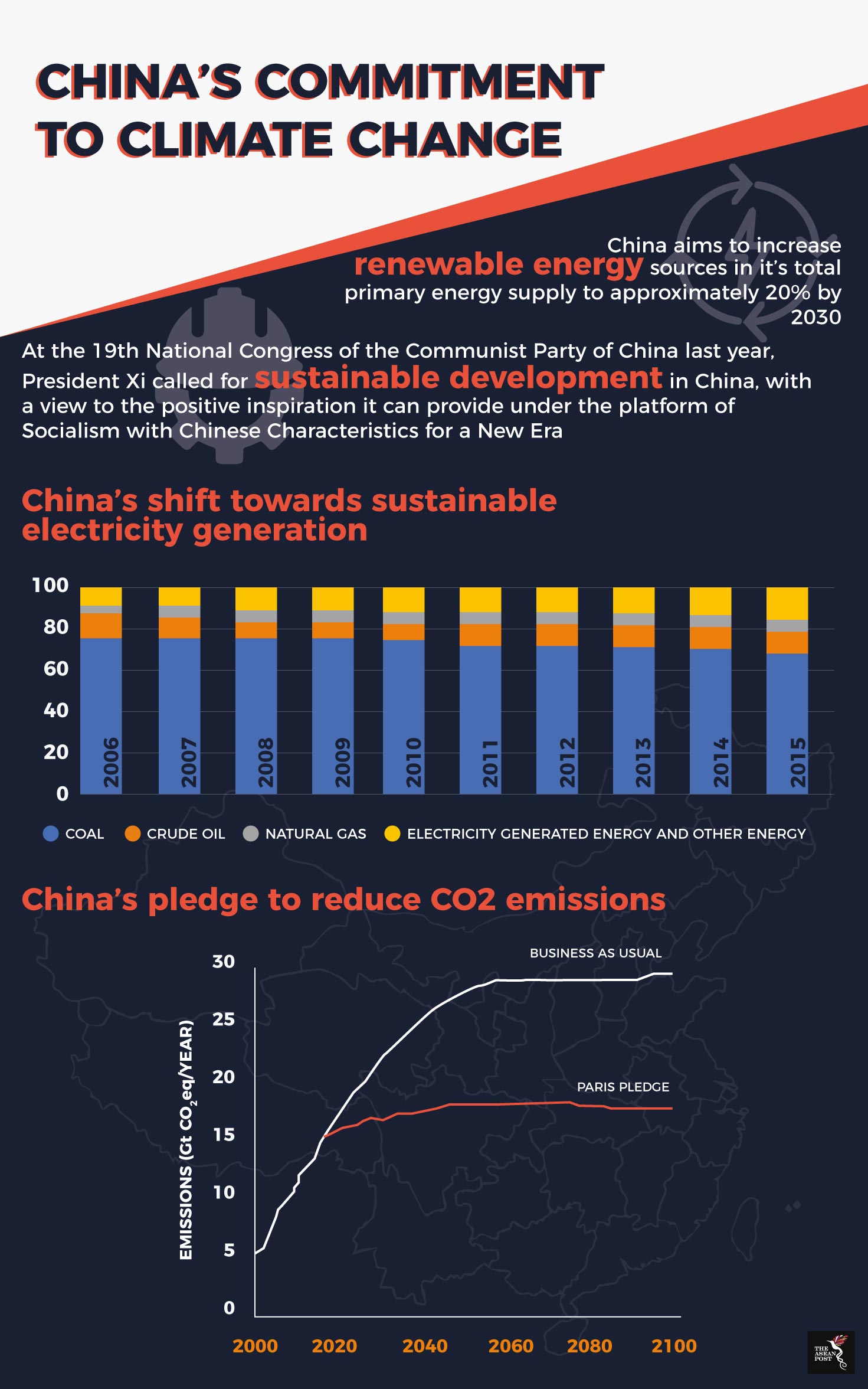

The second largest economy in the world has experienced a slump in economic growth of late and has begun to emphasise a more efficient use of its energy and resources. This means that Beijing is racing to develop and produce low carbon technologies which have been identified as the technology of the future. China has been investing billions in developing these new technology frontiers. In 2017, it announced a whopping US$360 billion investment in renewable energy by 2020 besides scrapping plans to build 85 coal-fired power plants.

Moreover, Beijing has been exporting its technology to other parts of the world. Chinese manufactured solar panels and wind turbines are considerably cheaper making them the preferred choice for many which was what led Trump to impose tariffs on Chinese solar panels early this year. Besides that, China has been actively funding sustainable projects and is a world leader in green bond issuances.

Over in Southeast Asia, there lies a significant chunk of green investment that has invited investments from China. A 2017 report by the United Nations and Singapore financial services provider, DBS, revealed that the market for green investment in ASEAN is projected to be worth a whopping US$3 trillion from 2016 to 2030, spread across four areas – infrastructure (US$1.8 trillion), renewable energy (US$400 billion), energy efficiency (US$400 billion) and food, agriculture and land use (US$400 billion).

Currently, there is a US$160 billion gap in green finance supply in the region as the projected average annual demand sits at approximately US$200 billion between 2016 and 2030. This translates to a necessary 400 percent increase in total annual green finance to satisfy ASEAN’s projected green investment appetite by 2030. The report stated that much of the current financing comes from the public sector but also highlighted that future private financing will increase from 25 percent to 60 percent whereas public financing will drop to about 40 percent.

China is already enjoying these investment opportunities via its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that cuts through large swathes of the region. In line with its goals, it is planning for a super grid in Southeast Asia which could complement the pre-existing ASEAN Power Grid initiative. Besides that, Beijing is a welcome investor in the solar photovoltaic markets of Vietnam, Thailand and Malaysia, just to name a few and has close connections with state utility providers in these countries.

One thing that China may lack is discourse power in the international arena when compared to the likes of the US and the European Union. However, with Trump’s stand on the environment, things could change. The world cannot afford a climate change naysayer leading the charge towards attaining the Paris pledge. In such a situation, turning to the next best thing might be the most reasonable option for all.