Over the years, a number of abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing nets have found their way around the coral reefs of Tunku Abdul Rahman Park in the Malaysian state of Sabah. Concerned that this may impact their business, divers operating within the protected marine park have removed the discarded fishing gear. But despite their best efforts, more and more abandoned or lost fishing nets are slowly drifting into the state marine park and threatening the coral reefs and marine life there.

The divers have highlighted the matter to Sabah Parks and the Sabah fisheries department, calling upon them to address the pressing issue. Their fear is not only that these drifting death nets are trapping marine wildlife and strangling coral reefs, but also having a negative impact on tourism activities in the area. The situation is bound to worsen if it is left to fester without effective and proper measures and enforcement in place. The divers have claimed to have removed fishing nets of up to 300 metres in length that were caught on reefs in the waters off the five protected islands of Gaya, Sapi, Manukan, Mamutik, and Sulug. In the last month, the group of divers have discovered and removed more than 13 ghost nets as a result of sponsored clean-up initiatives.

The abandoned, lost or discarded fishing gear (ALDFG), also known as ‘ghost gear’, found trapped in and around the coral reefs of Sabah Park is part of an estimated 800,000 tons of similar items entering the world’s oceans every year. The United Nations (UN) Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) estimates that ALDFG accounts for at least 10 percent of the total marine debris polluting the oceans every year.

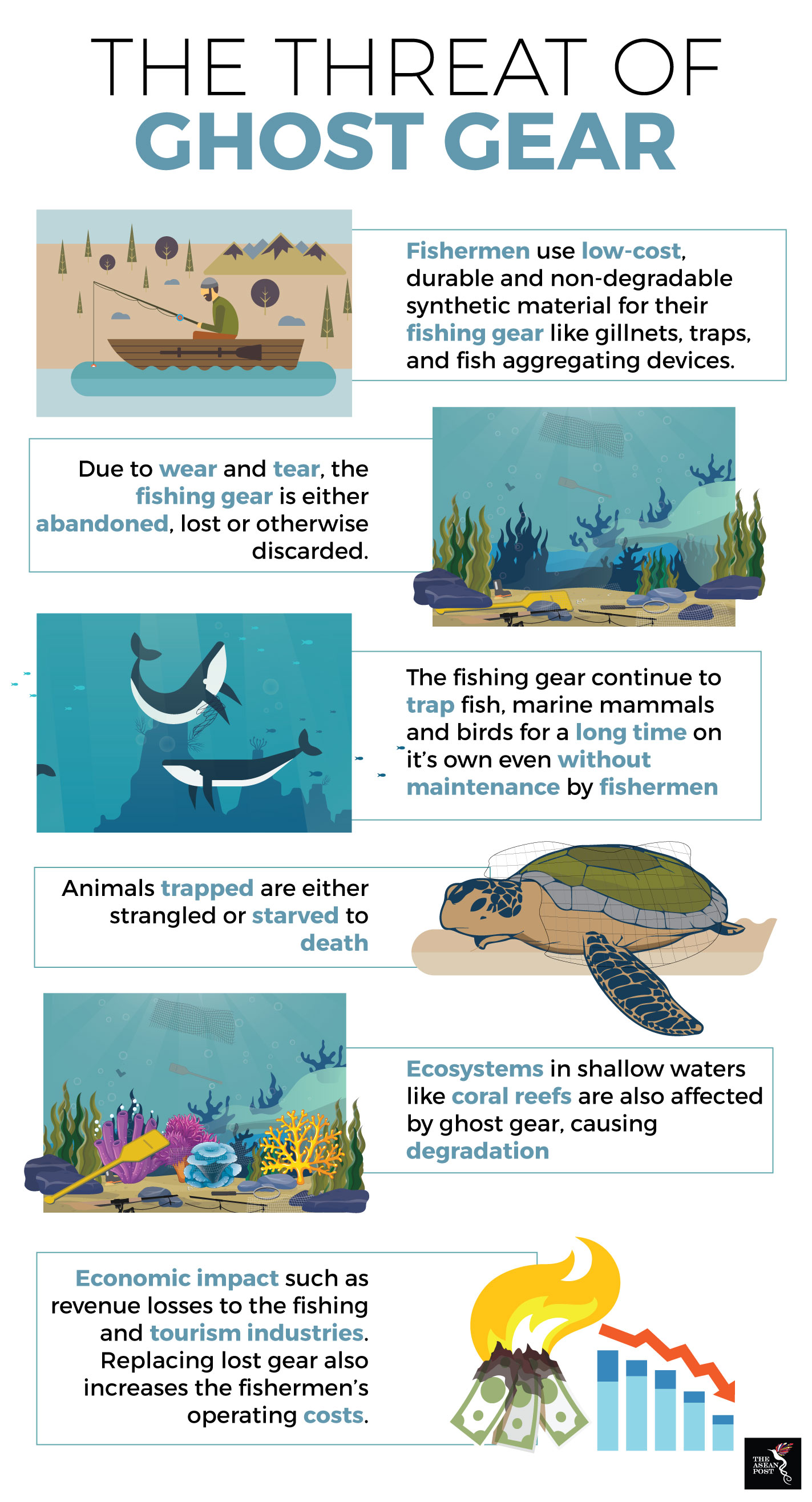

Fishing gear including nets, long lines, fish traps, fish aggregating devices or any man-made contraption designed to catch fish can become ghost gear if they are abandoned, lost or discarded in the sea. The ghost gear can cause considerable damage to marine wildlife, habitats and fish stocks. Left unattended, these gear which are often made of low-cost, durable and non-degradable synthetic materials, continue to catch marine wildlife for a long time. It has been estimated that fishing nets today can last in the sea for up to 600 years. Once caught in these drifting death traps, trapped animals would die, decompose and attract scavengers and other predatory animals, creating a vicious cycle of death. The ALDFG can also result in increased operating costs for fishermen due to the need to replace lost gear. The gear also represents a navigational and safety threat at sea issue.

Source: Various.

Source: Various.

In Southeast Asia, Indonesia is leading the way in addressing the pressing threat of ghost fishing by undertaking a pilot project on marking and tracking ghost gear, particularly focussing on the gillnet as it is the most common type of fishing net used. Pekalongan and Sadeng in Java were identified as pilot areas for the initiative due to their differing characteristics. Pekalongan has a low rate of ghost gear due to favourable weather conditions and sandy, muddy substrate which reduces snagging. In Sadeng, on the other hand, fishermen operate in deeper Indian Ocean waters in less favourable weather conditions, resulting in higher rates of gear loss. One study estimated around 35,000 pieces of gillnet lost annually in the Sadeng spiny lobster fishery.

Fishing gear marking that would enable recovered fishing gear to be tracked back and returned to its source has been slated as an effective way to significantly reduce the impact of ghost fishing, as well as illegal, unreported and unregistered (IUU) fishing. The Indonesian initiative, done in collaboration with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and World Animal Protection, will provide valuable field feedback on the efficacy, methodology and barriers to gear marking as a tool for addressing ALDFG and possibly IUU fishing. Ghost fishing and IUU remain key issues in the waters of Indonesia.

Thailand is also joining Indonesia in the global initiative to reduce the impact of ghost gear on marine life. Thai Union Group PCL, one of the world’s largest producers of shelf-stable tuna products and owner of seafood brands such as John West, Chicken of the Sea, and King Oscar, have joined the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI), founded by the World Animal Protection, in March this year. The GGGI is a cross-sectoral alliance committed to driving solutions to the problem of lost and abandoned fishing gear worldwide.

The efforts of the Indonesian and Thai governments need to be applauded. Gear marking is the first step to reducing ghost fishing. For it to be effective, it needs to be undertaken in conjunction with other measures including mechanisms to report lost gear and a circular economic approach to handling derelict nets. With more governments and stakeholders joining the initiative to explore various solutions to the problem, there is hope that this problem can be solved.