Halal (permissible or lawful in traditional Islamic law) products are an important component in the daily lives of most Muslims. Consuming or using non-halal products is considered a sin and unclean by many followers of the Islamic faith. Hence, there was no surprise when Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo's running mate Ma'ruf Amin revealed that he was planning to impose mandatory certification on all halal products next year. The announcement was largely met with approval from the world’s largest Muslim population.

Local media reports have portrayed the announcement as a political move by Jokowi and Ma’ruf to garner support before the April 2014 elections. The fact that observers and analysts have surmised that even Ma’ruf’s appointment as running mate was done by Jokowi in a bid to get support from Indonesia’s growing conservative community makes this a fair assessment.

While making halal certification compulsory in a country which has a large Muslim majority makes sense, there are certain concerns that come along with it. It would be prudent for the Indonesian government to look at these issues and assess how they may affect the general population there. Malaysia would be a good place to start as the neighbouring country has already implemented compulsory halal certification.

Source: Various sources

Source: Various sources

A step further

The practice of differentiating halal and non-halal products may have far-reaching implications especially in the face of an increasingly conservative demographic.

In August last year, Malaysian media reported that drinking cups placed next to a drinking water dispenser in a primary school were labelled “Muslim” and “non-Muslim”. While school authorities refused to comment when contacted, some critics went as far as to call the move a form of apartheid.

Activists and human rights observers have reasoned that the case was a manifestation of an increasingly conservative demographic which has also led to an increase in intolerance. In fact, United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur Karima Bennoune warned that the country had much to lose if the Malaysian authorities did not heed warning signs that the country’s culture of tolerance was under threat.

She especially expressed her concerns about the banning of books, including those describing moderate and progressive Islam, which she had attributed to “the growing Islamisation of Malaysian society and policies based on an increasingly rigid and fundamentalist interpretation of Islam”.

But Indonesia has in recent times also been accused of having an increasingly conservative and intolerant demographic and this was coherent with the findings of several studies which showed a strong support for Syariah law and punishing blasphemy. Human Rights Watch (HRW) have also come out and raised their concerns that the appointment of Ma’ruf could impede Jokowi’s promise to improve human rights in Indonesia, accusing the cleric of being central to some of the most intolerant elements of Indonesia’s contemporary religious and political culture.

“Amin has been central to some of the most intolerant elements of Indonesian contemporary religious and political culture, so fear of the negative impact he could have on the rights and safety of religious and gender minorities is well founded,” said Phelim Kine, deputy director of the Asia Division at HRW.

A conflict of interest

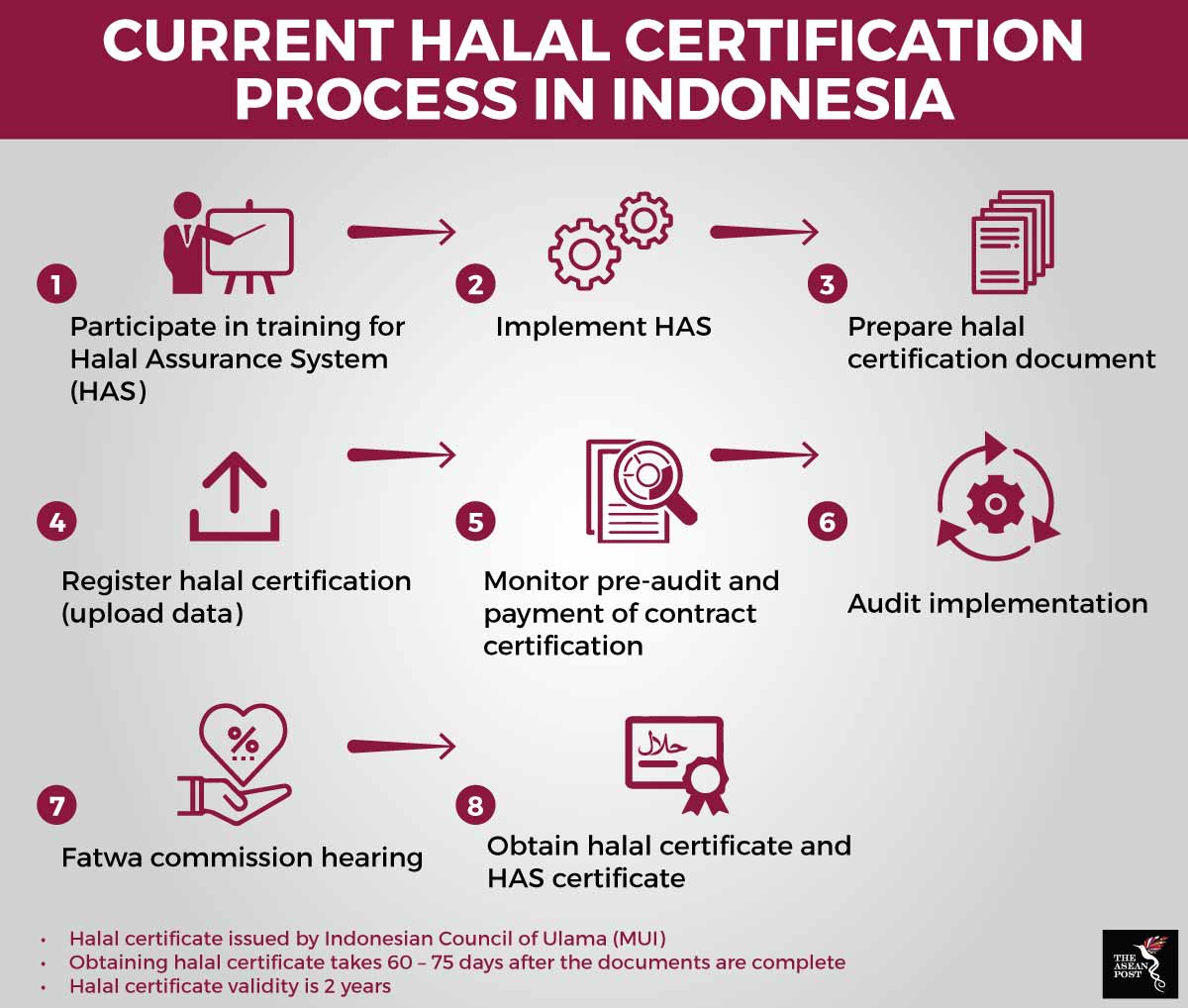

Another important point to note is the fact that Ma’ruf, apart from being Jokowi’s running mate, is also the leader of the country's top Islamic body, the Indonesian Council of Ulama (MUI). The reason this is important to note is because analysts have pointed out that making halal certification compulsory would also be an avenue for the MUI to generate revenue since the Islamic body would be the one responsible for providing halal certification at a cost.

A conflict of interest becomes apparent here as Ma’ruf is running for vice president and would effectively serve as Jokowi’s right-hand man. This presents a problem for suppliers and producers of halal products as they would possibly have to pander to the demands of the MUI and Ma’ruf to get the certification they need.

If Indonesia decides to go ahead with mandatory halal certification, then it would be in the country’s best interest to have Ma’ruf relinquish his position in the MUI as it would guarantee fairness in the halal certification process. This is especially so if Indonesia does indeed intend to become a global halal hub as favouritism (or even the remote possibility of it) may have adverse effects on quality.

While there are certainly advantages that can be gained through stronger focus on the halal industry, attention must be placed on how to go about doing so. Whether a compulsory halal certification may eliminate the issues and narratives that played out in Malaysia or further escalate zealousness is for scholars to debate and rightly so. Either way, Jokowi must be careful not to divide Indonesia in the hopes of gaining a few extra votes.

Articles selected as Top Stories of 2018 are those that were the most popular among readers of The ASEAN Post for the month in question.

Related articles:

Halal Indonesia: A booming industry