On 12 October, the Philippines’ Department of Foreign Affairs announced that the country had won its bid for a seat in the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC). This is despite the New York-based Human Rights Watch (HRW) having earlier campaigned for other countries to oppose the Philippines’ candidacy. The group cited the extrajudicial killings in President Rodrigo Duterte's anti-drug campaign with its United Nations (UN) director Louis Charbonneau having consistently voiced concern about the killings in the Philippines’ war on drugs going back to when he was the UN’s human rights chief.

“UN member countries should show their outrage at the Philippines and Eritrea by leaving two spots on the ballot sheet blank and keeping them off the council,” he said.

Perhaps another concern as far as the Philippines and human rights goes is the knack for long detentions without trial. According to a study released on 19 October titled “Understanding Factors Related to Prolonged Trial of Detained Defendants in the Philippines”, on 30 October, 2015, there were 8,915 pre-trial detainees in the six jails under study. The median stay for all these pre-trial detainees is 268 days, suggesting that 50 percent of inmates had already stayed in jail for more than nine months while still awaiting trial.

The person who conducted the study; assistant professor Raymund Narag at the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice, Southern Illinois University Carbondale; has even suggested that these unusually long periods of pre-trial detention contributed indirectly to the appeal of vigilante justice and Duterte’s war on drugs.

“This is what makes the killing of drug addicts and corrupt politicians attractive to the Filipino masses. It resonates squarely with the message of President Rodrigo Duterte of restoring ‘rule of law’ by any means necessary,” he writes.

Fuel to the fire

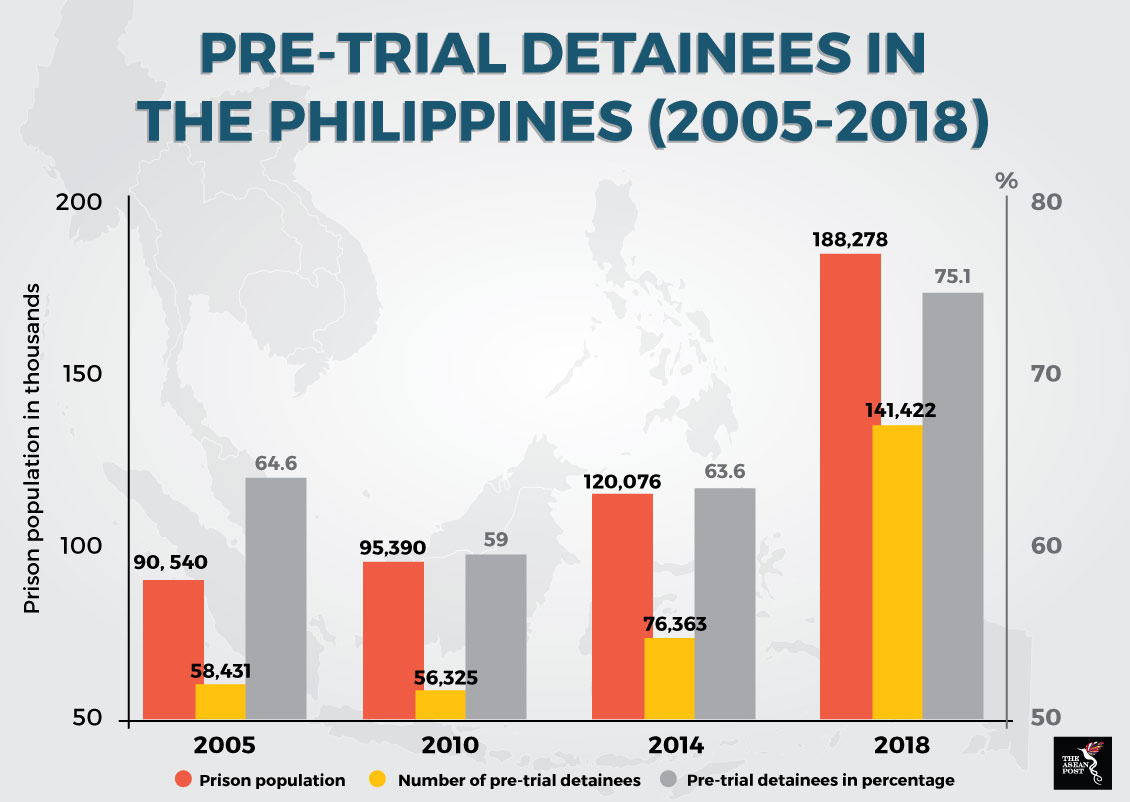

Statistics from the Birkbeck University of London’s and Institute for Criminal Policy Research’s World Prison Brief paint an even gloomier picture of Filipino prisons. According to the Brief, as of 2018, the Philippines is home to 933 prisons with a total prison population of 188,278 inmates where 75.1 percent are pre-trial detainees.

Source: World Prison Brief

Source: World Prison Brief

Narag surmises that the high cost of keeping inmates in prison per year (US$1,375 per inmate) has been a contributing factor to what has edged Filipinos towards favouring vigilante justice. According to Narag, Filipinos think that the purposeful delay is a manifest attempt to thwart the goals of justice. This, he says, especially benefits the rich and powerful accused as they can steer the wheels of justice toward their ends.

“Eventually, Filipinos lose trust in the justice system and take matters in their own hands,” he said.

This phenomenon, in turn, was possibly what gave rise to Duterte’s strong support when he announced his war on drugs campaign. Recently, Simon Shen, an associate professor and director of the Global Studies Programme, Faculty of Social Science, at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, also wrote that many ordinary Filipinos appear to favour eliminating drug dealers through summary executions. He said this was because they have lost faith in their country’s judicial system.

“Many ordinary people believe that since drug lords have powerful connections, it is almost impossible to bring them to justice through legal procedures,” he wrote.

Unseating the seated

Senior officials in the Philippines see the appointment of the country to the UNHRC as a vindication of Duterte’s crackdown on drugs. Duterte’s spokesman, Salvador Panelo, said in a statement that the international community had acknowledged Duterte’s campaign against illegal drugs, corruption and criminality as being essential to the protection of the “right to life, liberty and property.” Meanwhile, foreign affairs secretary Alan Peter Cayetano said it showed that “fakes news” and “baseless accusations” had no place in modern-day human rights discussions.

These affirmations go to show that winning its bid for a seat in the UNHRC would more than likely result in status-quo as far as Duterte and the war on drugs is concerned. Human rights activists say that since Duterte took office in June 2016, the “war” has resulted in the police killing more than 4,800 people.

If the intention is to hold Duterte responsible for all his extrajudicial killings, then sending mixed signals like re-seating the Philippines in the UNHRC has to stop and the international community must come to an agreement on how to ensure there are repercussions for such unlawful actions. However, what could also possibly help is to find a way to ensure that the initial catalyst for such killings – long pre-trial detentions – is stopped.

Related articles: