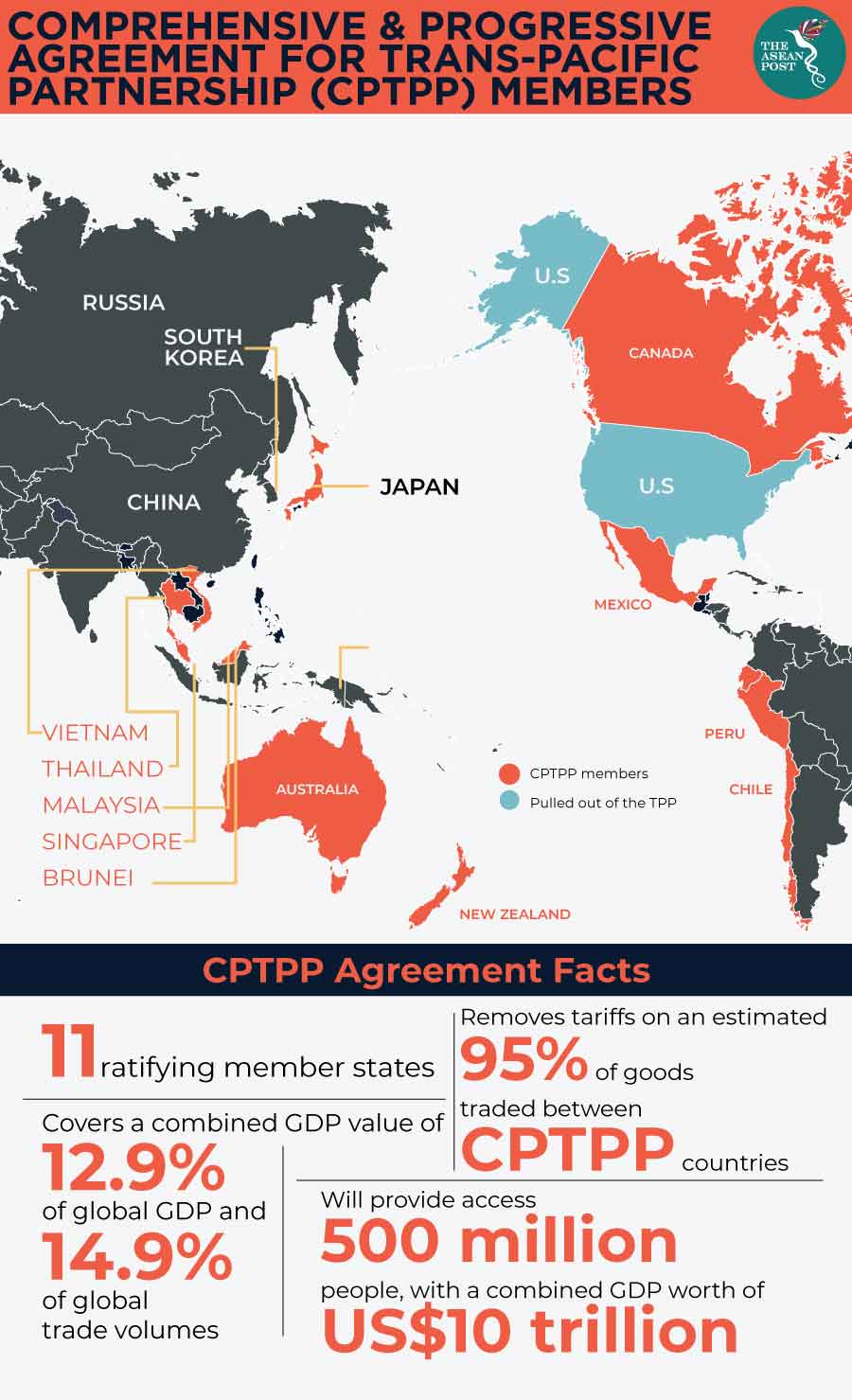

Despite the United States withdrawing from the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement), ASEAN countries will still largely benefit from the revamped version of the agreement. Now known as the ‘Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership’ (CPTPP), the remaining 11 participating countries will include Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam.

Trade talks were concluded in Tokyo, Japan recently, to iron out four outstanding issues, with all 11 remaining members agreeing to sign the multilateral agreement on 8 March in Chile.

The four outstanding issues pertained to the protection of Canada’s cultural industries, delays by Vietnam in implementing new labour laws, and exceptions requested by Brunei and Malaysia to adjust their preferential schemes with regard to state-owned enterprises.

“All 11 countries will join the signing ceremony,” said Toshimitsu Motegi, Japan minister of economic revitalisation, at a press conference held in Tokyo on 24 January. The treaty, however, only comes into effect once a minimum number of six members ratify it within their respective countries.

The agreement in its original form was called the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership and signed by just four countries in 2005; namely Brunei, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore. The United States then joined the pact and along with Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Singapore and Vietnam, signed the TPP12 in February 2016.

In 2017, United States President Donald Trump signed an executive order to revoke United States participation in the agreement, citing his dislike of multilateral agreements in general. During his presidential campaign Trump also promised to bring jobs back to the United States, a policy United States participation in the TPP would negate.

Although ASEAN countries would receive substantially reduced benefits under the CPTPP agreement; for most of them, participation is still better than nothing. The CPTPP agreement in its current form retains its original 1,000 provisions with the exemption of 22 suspensions. Suspensions refer to provisions which were ‘frozen’ but not removed. As most of these suspensions relate to United States intellectual property, they remained ‘frozen’ while member countries continued to iron out the four remaining provisions.

Brunei and Malaysia have requested for extended time to comply with terms that require them to adjust their preferential schemes regarding state owned enterprises. These were eventually also added to the ‘frozen’ provisions.

Mustapa Mohamed, Malaysia’s International Trade and Industry minister said Malaysia was satisfied with the outcome of negotiations and highlighted how the CPTPP agreement would provide access to a large combined market of 500 million people, with a GDP of US$10 trillion. The CPTPP agreement also removes 95% of tariffs for trade of goods between member states, with 90% of these removed immediately once the CPTPP agreement comes into force. By providing greater access to foreign markets, more jobs would also be created.

Meanwhile, ratifying the CPTPP agreement could force Brunei to diversify its economy. It has traditionally depended on oil and gas to supply about 60% of its GDP, according to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data gathered between 2007 and 2012. As of 2018, oil exports are still projected to account for up to 60.3% of Brunei's GDP, according to Bloomberg data.

For Singapore, the CPTPP agreement could supply new trade opportunities on top of existing trade benefits with fellow ASEAN nations Brunei, Malaysia and Vietnam. Under the CPTPP agreement, it will not face equity caps or the requirement for a local presence in these countries before it can invest there in fields like accounting, consulting, and engineering.

Vietnam would also have a wider market for its exports of footwear, textiles, and electronic products. Through this agreement, it will get a foothold in Canada, Mexico and Peru, with whom it currently does not have any trade relations. Yet tariff elimination would also expose its automotive and agriculture industries to heavy competition from overseas producers.

The remaining two issues were resolved with the use of side letters, or separate agreements with each CPTPP member country. Vietnam, which initially requested for more time to implement compliant labour laws will do so in its own time. Meanwhile, Canada, which insisted on protection for its cultural industries, will also obtain consent from the other CPTPP countries on an individual basis.

With the ratification of the CPTPP agreement, integration within the ASEAN bloc might be threatened as CPTPP-ratifying countries like Canada and Japan redirect trade from non-participating countries like Indonesia and Philippines to CPTPP members in order to benefit from lower tariffs.

One of the reasons why ASEAN countries have not shown interest in the CPTPP agreement is the high entry requirements. Getting their competition laws on par with those of other CPTPP member countries is another barrier. Meanwhile other ASEAN countries, like Indonesia, remain less interested in joining the CPTPP after the withdrawal of the United States.

Yet should circumstances change for Thailand, Philippines and Indonesia, they could still become party to the CPTPP agreement. A restructured deal could even draw the United States back into the CPTPP fold, Donald Trump stated recently. On the other hand, a CPTPP agreement with the United States included could tip the balance of interests once again. There would be no point in negotiating a new CPTPP agreement which benefits only the United States.

Recommended stories:

Thailand delays elections yet again