There is growing concern about the European Union’s (EU) proposed suspension of its Everything But Arms (EBA) trade agreement with Cambodia, a move which could set the country back years.

Established in 2001, EBA gives 49 of the world’s least developed countries tax-free access to vital EU markets for their exports except for arms and ammunition.

While the EU has always warned that EBA preferences can be removed if beneficiary countries fail to respect core United Nations (UN) and International Labour Organisation (ILO) conventions, there is a real threat that this could come at the cost of massive unemployment and stagnant growth in Cambodia.

Role in economy, employment

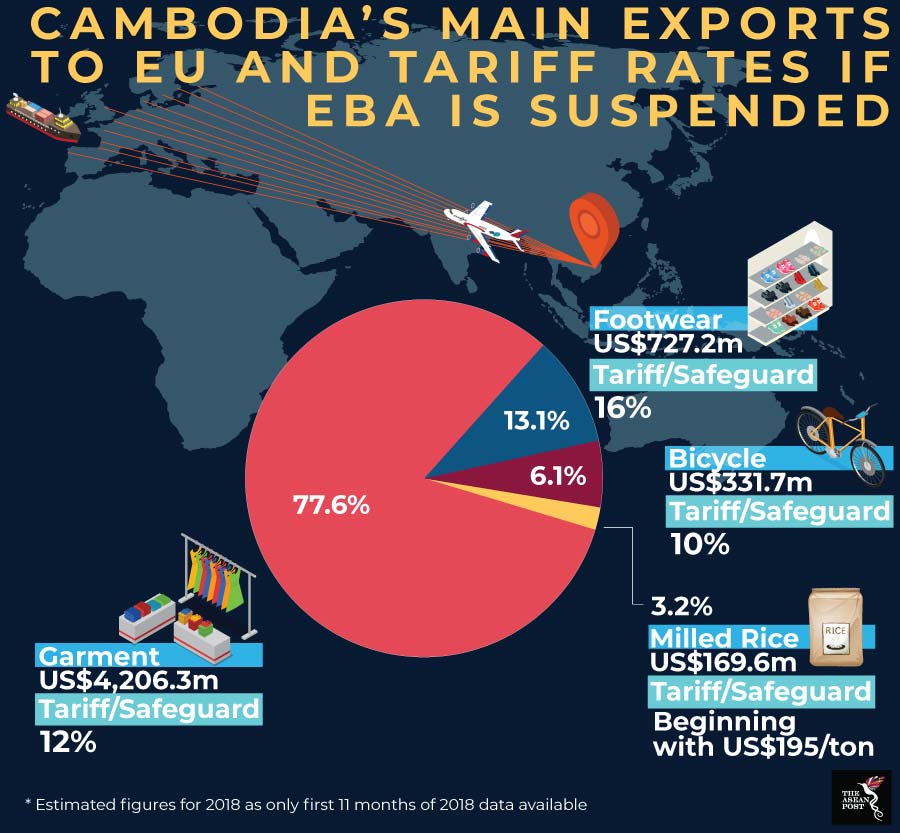

Making up 39 percent of the country’s total exports, the garment and footwear sectors employ more than 700,000 Cambodians and are the country's largest employers. Cambodia’s exports to the EU totalled US$5.47 billion last year – more than a third of its total exports – with textiles and footwear making up the majority of that sum.

After the Garment Manufacturers Association in Cambodia warned of a halt in the country’s development in February due to the possible EBA suspension, the National Union Alliance Chamber of Cambodia (NUACC) last week said that the lifting of the tariff system will affect the livelihoods of about three million Cambodians.

On 2 May, a coalition of 20 international brands which source from Cambodia – including Nike, adidas and Levi Strauss – wrote a letter to Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen outlining their concerns that the labour and human rights situation in Cambodia is posing a risk to trade preferences for the country.

The EBA suspension would increase tariffs in the garment sector by 12 percent and the footwear sector by eight to 16 percent, costing US$676 million in additional taxes. The fear is that the rise in tariffs could lead to investors moving to other countries that enjoy EBA, thus affecting Cambodian jobs.

The NUACC estimated that some 43 percent of garment workers (nearly 225,000 people) and 20 percent of footwear workers (more than 20,000 people) would be left unemployed, stating that “research suggests and history demonstrates that economic sanctions lead to an increase in poverty – especially among women, minority communities and other marginalised groups.”

Why is the EBA being removed?

The EBA has led to a 630 percent increase in Cambodia’s garment and footwear exports to the EU since 2008, helping the Cambodian economy to grow by 7.5 percent in 2018 according to the World Bank. The two sectors recorded a five-year high in 2018, rising by 17.6 percent – more than double the 8.3 percent increase in 2017.

Helping to lift one-third of the country's population out of poverty between 2007 and 2014, the garment and footwear sectors are now at risk following the EU’s decision to start an 18-month review on whether to suspend duty-free preferences in February after the European Commission called Cambodia out for its “deterioration of democracy, respect for human rights and the rule of law.”

The EU warned Cambodia that it could lose this special status after last July’s elections kept Hun Sen in power and saw his Cambodian People's Party win all parliamentary seats.

His victory came after a political crackdown which saw the dissolution of the opposition Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP), the detention of its leader Kem Sokha, and the banning from political activity of 118 senior CNRP members.

Hun Sen has ruled Cambodia for more than 34 years, and the EU Foreign Affairs Council has deemed the recent 2018 elections as “not legitimate”.

Correct approach?

Is the EBA suspension – which, if confirmed, will only come into effect in August 2020 – really the best way to address Cambodia’s poor human rights record and democratic strength?

Refusing to budge, Hun Sen considers the EU’s talk of human rights violations and democratic reforms as interference in the country's internal affairs, and an EBA suspension would hamper the remaining goodwill the Cambodian government has with the EU – and could lead to increased dependence on China.

As Darren Touch, a Master of Public Policy and Global Affairs candidate at the University of British Columbia wrote, in Cambodia, like many other post-colonial countries that have gone through years of civil wars, the democratic progress takes time.

With the World Bank stating that 4.5 million Cambodians, or 28 percent of the population, remain “near-poor”, mass unemployment would create conditions for political instability – this is a risk Hun Sen will have to factor in when moving forward with the EU on EBA negotiations.

Related articles:

The rising cost of Hun Sen’s rule in Cambodia