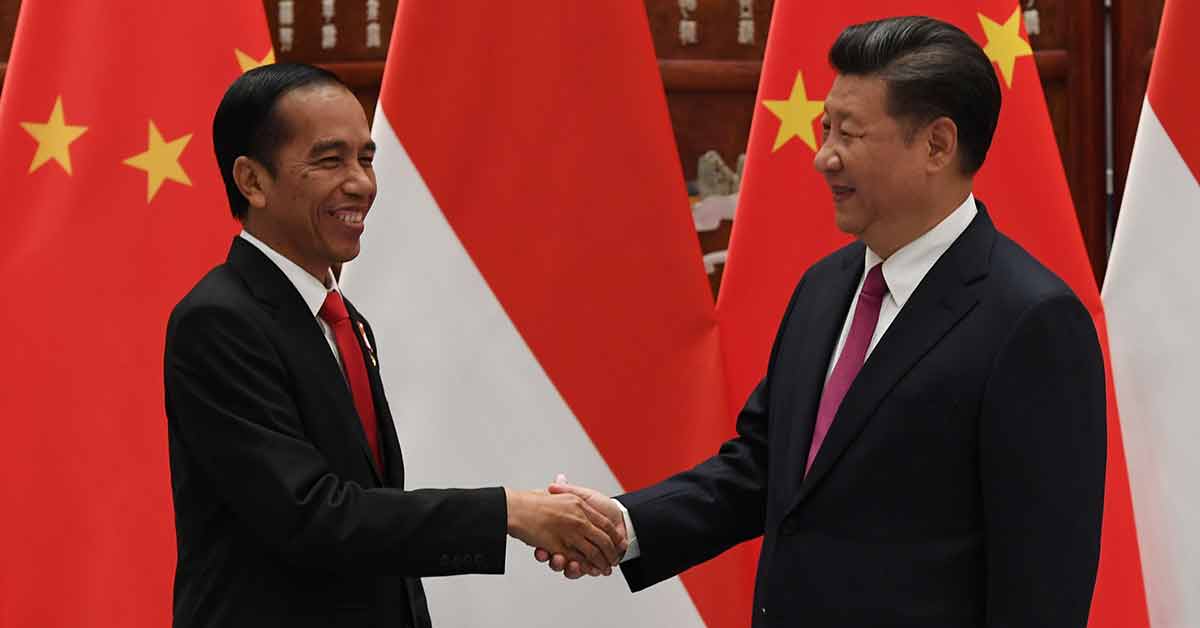

In early September, as the COVID-19 pandemic was raging, China hosted the “Wonderful Indonesia’” event at the International Cultural Exchange in Beijing. The exhibition showcased Indonesia’s diverse culture, from its coffee, food and coconut beverages to traditional Indonesian handicrafts like batik.

The event exemplified the soft power ties that have grown between Jakarta and Beijing in recent years. Although underreported, this partnership has intensified since the enunciation of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013. This not only involves growing cultural ties, but also significant educational exchanges and increased people to people ties.

China views Indonesia as one of the focal points in the BRI, especially along the vital maritime routes of the initiative. There has been a notable rethink in Beijing’s policy apparatus towards Indonesia, fuelled by the realisation that growing economic ties between the two governments must be complemented with culturally-based exchanges.

Relations between Jakarta and Beijing are very much overshadowed by recent history, including the widespread anti-Chinese sentiment in Indonesia that is a legacy of the Suharto regime and recent maritime frictions near the Natuna Islands in the South China Sea.

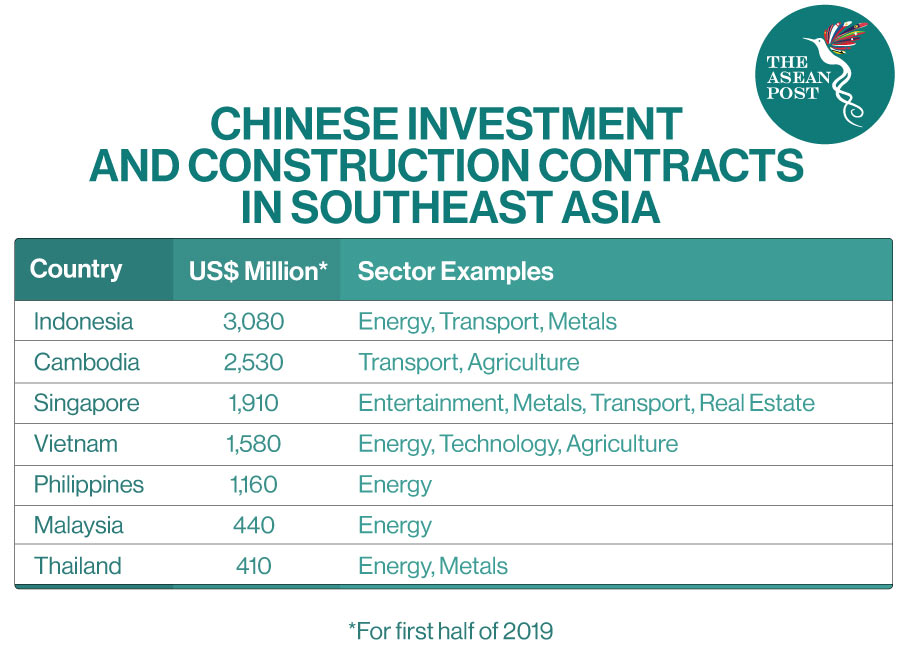

However, the two countries have interdependent interests: the implementation of the BRI, and increased connectivity and influence in Southeast Asia for Beijing, and foreign direct investment (FDI) and trade to further the ambition of transforming the country into a “global maritime fulcrum” for Jakarta. Soft power is increasingly playing an important role in pushing forward these complementary economic policies.

Understanding Anti-China Sentiment In Indonesia

As soon as the BRI was announced in 2013, Beijing signed a cooperation agreement intended to promote increased Chinese exchanges with Indonesia. This resulted in now regular events organised across Indonesia such as the 2017 China-Indonesia Cultural Festival in Malang, East Java, and a joint cultural performance and Lantern Festival celebrations in Jakarta. Such events exhibit aspects of Chinese culture, such as traditional dance and martial arts, that would have been rare a decade ago.

Such activities appear to aim at re-introducing China and its culture to Indonesian society. Indonesia has a long history of prejudice against China, rooted in negative sentiments towards its ethnic Chinese minority. To this day, anti-Chinese sentiment remains widespread within Indonesian society.

Xenophobic sentiment has strengthened as China's economic activities in the country have grown alongside the COVID-19 pandemic. Amid unfounded popular fears within Indonesia that mainland Chinese workers are taking local jobs, widespread conspiracy theories alleging that imported products have been deliberately infected with the COVID-19 virus and that Chinese security forces are intervening in domestic politics have been circulating.

A recent study also found that Beijing’s domestic and foreign policy actions have influenced Chinese Indonesians across the archipelago.

In this context, when President Xi Jinping initiated the BRI, he understood the importance of using cultural activities to ease the implementation and soften the image of the People’s Republic.

The “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road,” the BRI’s main strategy document, emphasises “cultural exchange” as a vital part of the realisation of the initiative.

Culture And Education

Cultural activities have been institutionalised by the two countries with the establishment of the first China-Indonesia Cultural Forum in January 2019. As part of the forum, there is also a planned 10,000 square metre centre in Gunung Batur, Bali which is envisioned as a place for China and Indonesia to get to know their respective cultures.

Indonesian media also reported that there will be an orphanage and a multi-lingual (English, Bahasa Indonesia, and Chinese) university built in the area.

Widespread efforts at collaboration and exchanges have also taken place in film, music, and photography.

Besides cultural events, soft-power ties between Indonesia and China also include growing academic and educational activities. China has actively tried to attract Indonesians to study in China.

The China Education Exhibition (CEE), for example, has been held 16 times as of writing, under the joint coordination of the Chinese Service Centre Exchange (CSCSE) and Indonesia’s Ministry of Education and Culture.

China is also offering scholarships to Indonesians through various state-led initiatives at designated universities. As a result, mainland China has become a key destination for young Indonesians to pursue higher education.

In 2017, the number of Indonesians studying at Chinese universities reached 13,700, and has increased by around 10 percent annually.

The two countries also inked an agreement to strengthen their education partnership in 2017. This was the third education partnership signed in the post-BRI era, after finalising an agreement on scholarships in 2015 and mutual recognition in academic higher education qualification in 2016.

The education partnership between Beijing and Indonesia started as early as 2000, particularly in informal Chinese language training. However, as China’s economic foothold has expanded, interest in learning the Chinese language has grown among Indonesians.

As a result, various Chinese language centres have been established in the archipelago. Moreover, despite facing various issues and frictions, China has also established Confucius Institutes in the country under the mediation of the Indonesian Coordinating Board for Mandarin Language Education. Alongside the promotion and teaching of the Chinese language, these institutes also conduct exchanges and activities that promote Chinese culture.

In recent years, China has also strengthened its formal education partnership with Indonesia. Student-teacher exchanges have been increasingly carried out to encourage students and teachers to learn about each other's language and culture. Universities and other institutions from both countries have also been collaborating to learn from one another.

For example, Indonesia's National Research Institute (BPPT) has signed partnerships with the Nanjing Railway Technology Institute and the Chinese HTGR (high-temperature gas-cooled reactor) research centre at Tsinghua University to learn about fast train development. The two countries have also initiated several joint laboratories, including a Biotechnology and High-Temperature Gas-cooled Reactor, the Indonesia China Transfer Technology Centre, and Scientific Exchange Programs.

People To People

In the past few years, China has also increasingly strengthened relations with non-state partners and organisations. In September 2018, for example, China’s State Administration for Religious Affairs made public its intention to pursue a partnership with Muhammadiyah, one of Indonesia’s largest Islamic organisations. Besides these collaborations, several public academic discussions on the role of culture in China-Indonesia relations have also been held.

All of this has taken place in the context of growing people-to-people exchanges. The Indonesian government’s policy of granting visa-free visits to Chinese citizens has contributed greatly to increasing the number of Chinese tourists visiting Indonesia.

In 2020, the number of Chinese tourists to Indonesia increased by 17.58 percent. This number is expected to grow, as the government in Jakarta has been making efforts to bring more Chinese tourists to the country. The most crucial of these is a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with China on tourism investment development to attract 10 million tourists from China per year. This, however, remains delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

China’s soft-power reach is expanding alongside its economic foothold in Indonesia. Despite major inroads made by the BRI, its full reach remains geographically limited at present, owing to a focus on Indonesia’s major cities. It is nonetheless making inroads.

The cultural activities carried out revolve around socialising Chinese cultural elements rather than on establishing a common vision or addressing the source of anti-Chinese sentiments within Indonesia. As a point of comparison, in Africa, it is reported that Chinese state cultural outlets have been used to promote how Chinese investments may benefit the people there, whereas in Indonesia no such operation or narrative has yet been implemented.

The above examples provide evidence that China’s bridgeheads in Indonesia are not restricted to the economic sphere but are beginning to expand into cultural, educational, and people-to-people realms. With China working hard to implement the BRI and the COVID-19 outbreak compounding negative attitudes towards China and its citizens; Indonesia needs to be ready for Beijing to expand these cultural promotion strategies in the months ahead as it seeks to soften perceptions of China within Indonesia.

As Xi Jinping himself stated regarding the education of his own population on the country’s ‘Core Socialist Values’: “Preparatory work must be done. One must not worry about it taking too long, for the work will be accomplished in the fullness of time.”

Related Articles: