Indonesia has a serious issue as far as meeting the challenges of the Fourth Industrial Revolution go. The quickly evolving landscape and potential demands on the country’s workforce is shaping into a real concern. ASEAN’s largest economy could be running out of time to equip its people with the necessary skills and knowledge to stay competitive.

Already, the country has been forced to come to terms with having the highest youth unemployment rate in the region (approximately 15 percent), according to data from the World Bank.

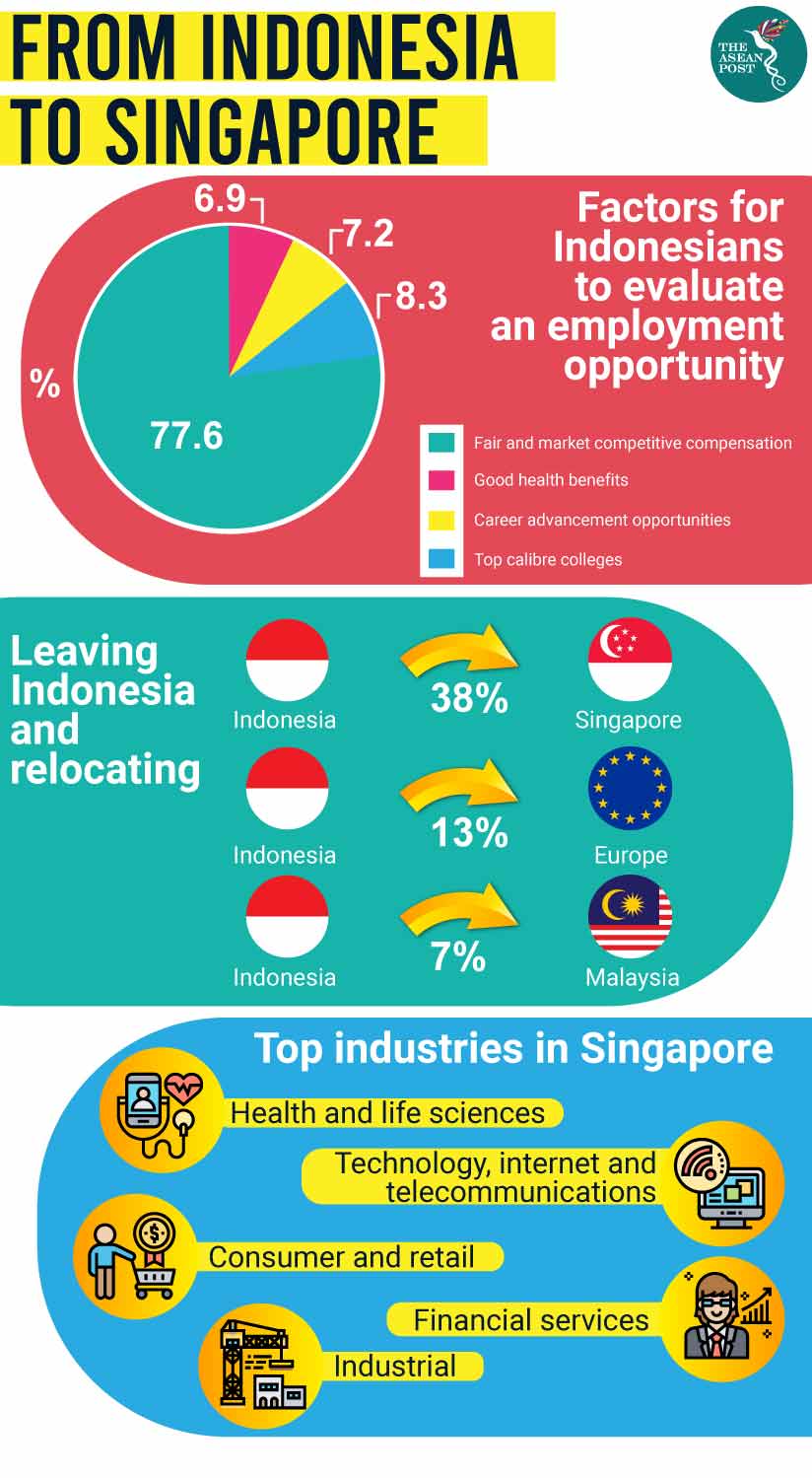

With the lack of opportunities at home, many Indonesians are now looking beyond their shores. According to RGF International Recruitment’s Talent in Asia 2019 report, an overwhelming majority of Indonesians would choose to relocate to Singapore (38 percent), if given the chance, above any other country. If not Singapore, local talent would consider a move to Europe (13 percent) and Malaysia (seven percent).

While other ASEAN countries surveyed (Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, and the Philippines) also chose Singapore as their prime destination, Indonesian talent still came up highest on that front. Meanwhile, 21 percent of Singaporeans said China was their destination of choice when seeking employment abroad.

The report also noted that the majority of Indonesians surveyed (76.5 percent) chose fair and market competitive compensation as their reasons for evaluating an employment opportunity.

Moving to, and seeking employment in Singapore, however, would not be very easy for many Indonesians though.

Singapore’s wants, Indonesia’s needs

While Singapore employers have stated that their number one concern for the future is talent shortage (84 percent), this does not immediately signal good news for most Indonesians.

“When hiring talent, local employers value industry expertise above all else - but are equally as concerned about soft skills such as accountability and the ability to adapt. For more technical roles, core competencies are key, but in certain sectors and functions, the skills can be learned - while various attributes cannot,” RGF noted in its report.

As far as industries go, Singapore’s Ministry of Health predicts the country will need 300,000 more healthcare professionals by 2020.

“As the government places more focus on research and development in the healthcare sector, there are abundant opportunities for talent with a range of experience and skills to find a fruitful career in this blossoming industry,” RGF stated.

After healthcare and life sciences, the industry with the second highest demand for talent in Singapore – unsurprisingly – is technology, internet and communications.

The problem, as far as Indonesians go, is a lack of expertise.

“This is an effort to improve the quality of human resources. Hence, universities can no longer afford to produce graduates that are unable to meet the requirements of the industry," he said after attending the Plenary Meeting of the Indonesian Economic Scholars Association (ISEI) at Stikubank University, Semarang, on Monday.

But this is at the higher education level. The root of the problem may, in fact, come much earlier than that.

Apart from Indonesia’s consistently low rankings in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) results, numerous reports have also indicated that there exists a problem plaguing Indonesian schools. A report entitled “Beyond access: Making Indonesia’s education system work” from the Sydney-based Lowy Institute found that one of the main problems with Indonesia’s education system stems from “politics and power”. The report claims that there is little incentive for old elites to drastically overhaul the country’s education system, arguing that they would rather exploit it to “accumulate resources, distribute patronage, mobilise political support, and exercise political control.”

According to the Lowy Institute, problems which have stemmed from this lack of political will include corruption, poor quality of teaching and staff absenteeism.

Looking at RGF’s country profile for Indonesia, it is likely that Indonesians want to move out mostly to look for better job opportunities with better pay. Meanwhile, Indonesia has highlighted talent shortage (50.4 percent) as its biggest concern. The issue here seems to be a larger one involving the country’s economy and policies. One thing for certain is that Indonesia must up its game as far as quality of education goes so it can increase skills development not only in line with the demands of other countries but its own as well.

Related articles: