Tsunamis in Indonesia claimed more than 2,600 lives last year – a number which could have been much lower had their Tsunami Warning System (TWS) been in working condition.

A tsunami after a 7.5 magnitude earthquake killed around 2,200 people in Palu on Sulawesi island in September and another tsunami after the Anak Krakatoa volcano erupted in the Sunda Straits in December killed around 400 people in Java and Sumatra. These tsunamis were Indonesia’s third major natural disaster in six months following a series of earthquakes on the island of Lombok in July and August.

For both tsunamis, the warnings did not reach residents in time or were not issued at all – shining an unwanted light on Indonesia’s level of preparedness for natural disasters and the state of its TWS. During the Palu tsunami, officials retracted a tsunami warning just minutes after the first waves hit the shore – later claiming they had a lack of data to prove the tsunami was on its way. As the Sunda Straits tsunami was caused by a volcanic eruption instead of an earthquake, no early warnings were issued.

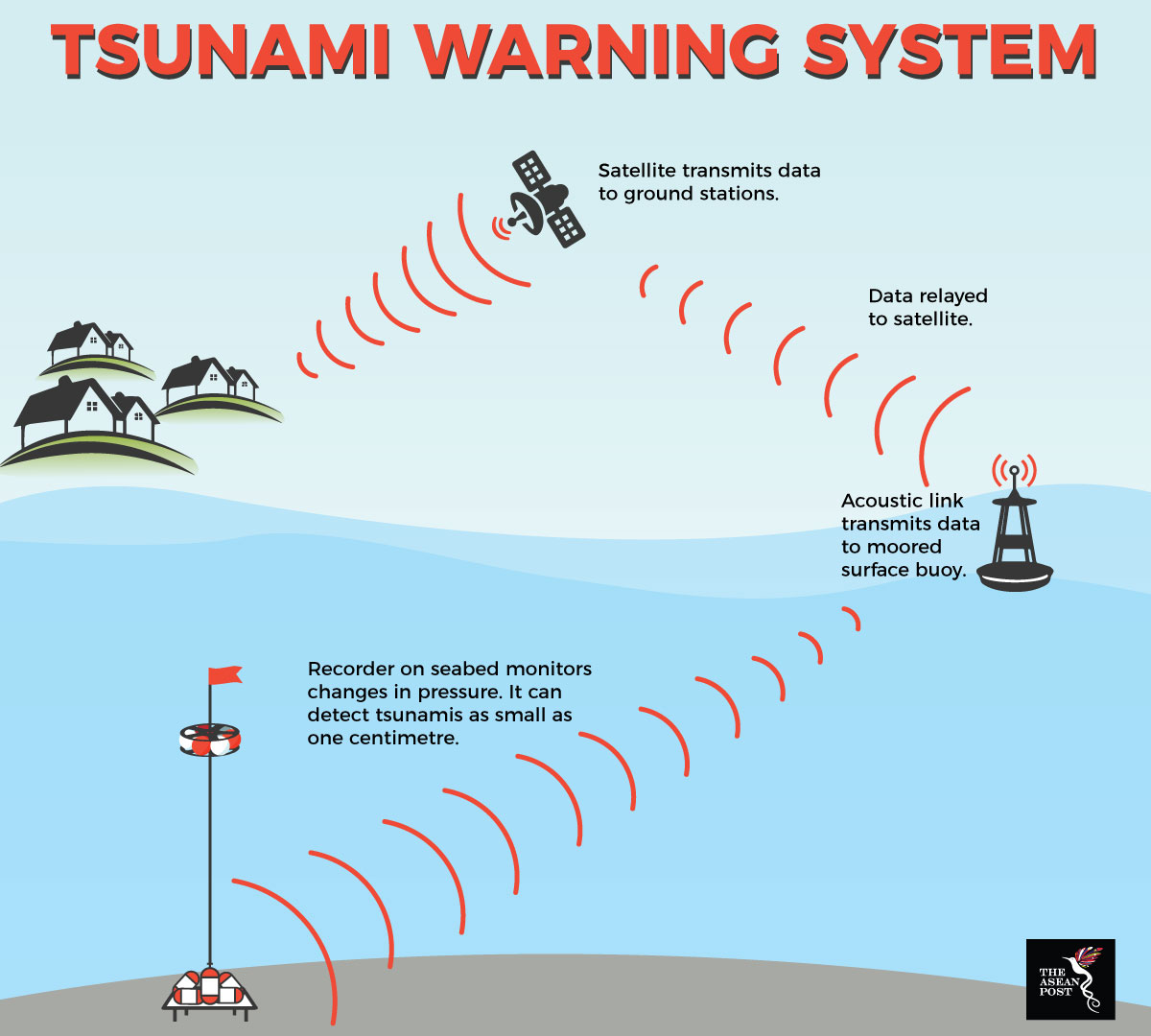

A TWS uses buoys and satellites to measure wave heights after an earthquake and can provide warnings of up to several hours, depending on where the earthquake was located. After receiving a signal of unusual activity from sea bed sensors, the buoys then transmits the data to satellites – which then transmits the warnings to ground stations and tsunami warning centres, which then informs the public to evacuate via sirens or text messages.

Indonesia’s location along the “Ring of Fire” – where several tectonic plates meet and frequently cause volcanic and seismic activity – has seen it hit by numerous earthquakes and tsunamis, making the nation-wide implementation of a TWS crucial in preventing unnecessary loss of lives in the future. Although Indonesia has an existing system of buoys, it is not in use due to several factors such as neglect and vandalism – with budget constraints and the lack of strong political will preventing upgrades or new installations.

Source: Various

Jokowi calls for changes

Speaking at a cabinet meeting last month, Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo stressed the need for the immediate implementation of an early warning system and disaster education at school.

“We must ensure that early warning systems are well-organised so that the public will know (what to do when disaster strikes) and we can minimise the number of casualties,” Jokowi said. “This must be carried out on a massive scale so that all are aware of and understand our condition,” he said of rolling out disaster education programmes in schools.

His views were shared by Indonesia’s tourism minister Arief Yahya, who last month called for early warning systems for tsunamis – especially at tourist destinations. On Sunday, the head of the Bali Disaster Mitigation Agency proposed the installation of 10 more tsunami warning sirens in the waters off the resort island.

But looking beyond the initial investment of a nation-wide TWS, its implementation and long-term success lies in the proper maintenance and care of its network of buoys and sensors. The establishment of clear emergency guidelines and the preparedness of the area’s residents to evacuate when in danger are just as important.

The cost of nation-wide coverage

According to Indonesia’s National Disaster Mitigation Agency (BNPB) spokesman Sutopo Purwo Nugroho, the country has only 56 tsunami sirens installed nation-wide out of an estimated need for 1,000. In addition, the network of 22 tsunami-detection buoys installed across Indonesia have not been operational since 2012 because of vandalism, theft of the sensors, lack of maintenance or neglect.

Sutopo added that the cost of installing buoys to cover the whole country would be around US$484 million, which is approximately the same figure Indonesia spent on natural disaster management last year.

Indonesia wants to take a leaf out of Japan’s book and is in discussion with it on the option of installing seabed cables with sensors that can detect tsunamis and earthquakes. Although the cables would transmit data quicker than buoys and is less prone to theft, its cost – US$20 million a year for every 200 kilometres – may be prohibitive.

However, with Indonesia’s Agency for the Assessment and Application of Technology estimating that the country loses US$2 billion each year from natural disasters, the cables and sensors may be more sustainable and economical in the long-run. The Palu earthquake and ensuing tsunami alone was estimated to cost the local government’s economy at least US$911 million, according to BNPB data.

The 2004 tsunami which affected 14 countries and killed more than 230,000 people was one of the worst disasters in modern history. It claimed over 167,000 lives in Indonesia and is still fresh in the minds of most in the region. It was the impetus many governments – including Indonesia – needed to install early warning systems for tsunamis. Now that the systems are failing, Indonesia should ask itself how ready is it for the next big natural disaster?

Related articles:No warning meant no escape from Indonesia tsunami

Bali raises volcano alert to highest level: officials

Towards sustainable tourism in ASEAN