The notion of repatriation for the 689 Indonesians associated with terrorists and violent-extremist groups in Syria has led to controversy in Indonesia. Public debate is not only divided on whether the government should repatriate them or not, but also whether or not their nationality should be revoked. In responding to that, the Indonesian government has just declared its decision to not repatriate them. It remains unclear whether the government will create an exception for children, as there was only a vague statement of possible repatriation for children under 10 years of age by Mahfud MD, the Coordinating Minister of Political, Legal and Security Affairs. There has been no further explanation of the reasoning behind this selective repatriation. However, the practice of providing protection for children that are 10 years old or younger is not common as the definition of children accepted by both local and international regulations is 18 years old and under.

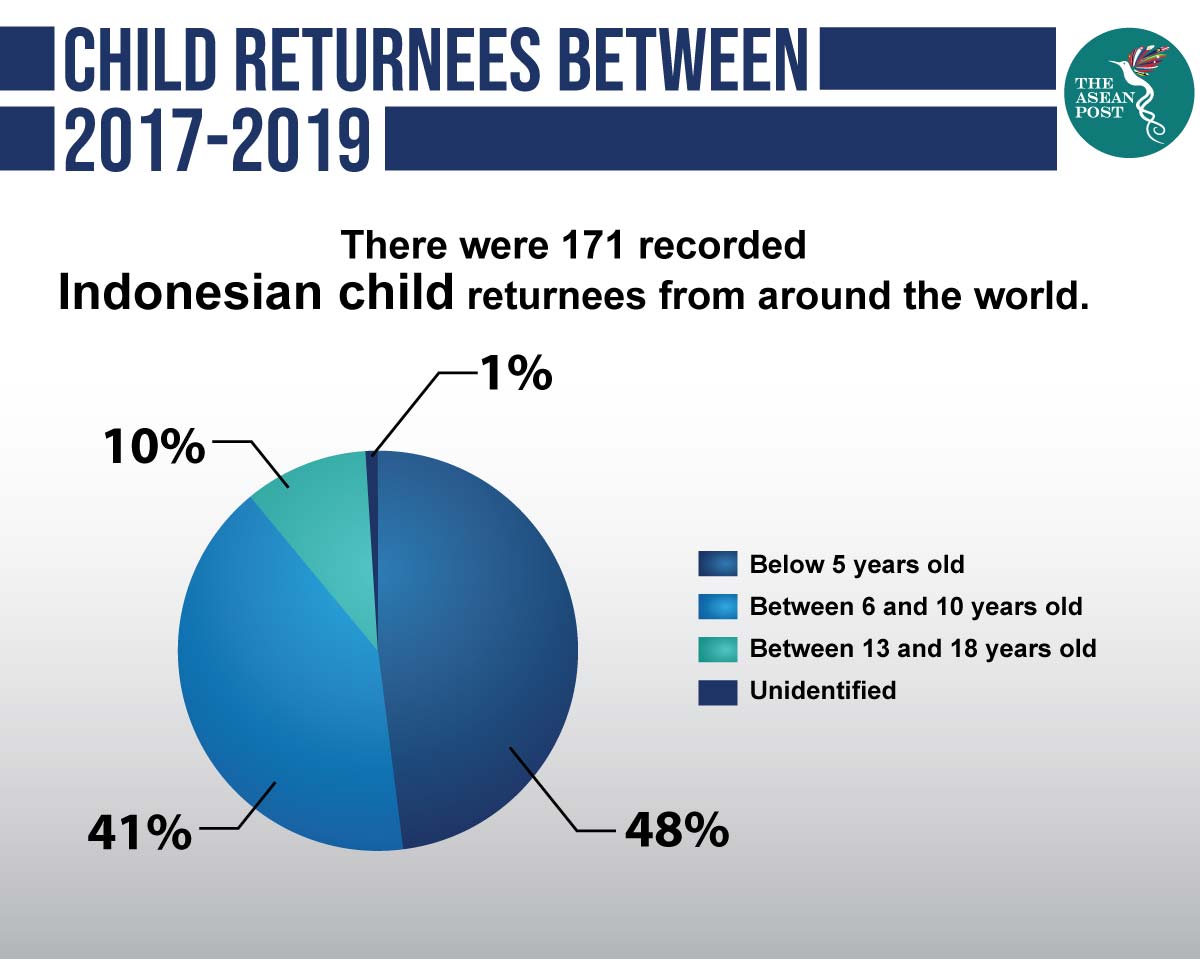

The number of Indonesian children who are associated with terrorists and violent-extremist groups in Syria remains unclear. In accordance with data from the Civil Society Against Violent Extremism (C-SAVE), there were around 171 children deportees/returnees between 2017 and 2019. Of this number, 48 percent consists of children below five years old, 41 percent fall between the ages of six and 12, 10 percent fall between the ages of 13 and 18, and one percent remain unidentified. From this data, it is estimated that significant numbers of Indonesian children are currently in Syria.

Children recruited and exploited by terrorist or violent extremist groups and demobilised to a country other than their country of origin are in vulnerable positions. These children are often victims of exploitation and need comprehensive psychosocial support. Recruitment and involvement of children with terrorist and violent extremist activities must be regarded as a serious crime against children that can lead to exploitation. This is due to the power imbalance that pressures children to join these groups.

As a party to the Convention of the Rights of the Child 1989 (CRC), Indonesia is subject to the convention and must comply with its provisions. Indonesia must ensure the protection and fulfilment of the rights of all children, including basic rights for these Indonesian children in Syria. Contrary to this, the government has widely broadcasted the idea of removing their nationality, and worse – even released an official statement of refusal for repatriation.

Notwithstanding, article 1 of the CRC stipulates that child protection applies to all individuals below 18 years old, which means the Indonesian government shall not remove citizenship and begin repatriation for all Indonesians below 18 years old in Syrian camps as it is mandated by the Convention, not only for those below 10 years of age as previously mentioned.

Revoking the nationality of these children will result in their statelessness. It will cause detrimental harm as it deprives their basic rights, including rights of particular importance to the rehabilitation and reintegration of children exposed to terrorism and violent-extremism, the right to security, access to health care, and access to education.

Indonesia must protect the right to a nationality of children recruited and exploited by terrorist groups in Syria and avoid all policies and actions that lead to statelessness. Article 7 (1) of the CRC governs the right to nationality; it stipulates that every child has the right to acquire a nationality. Subsequently, article 8 (1) of the CRC prohibits arbitrary deprivation of citizenship and stipulates that states undertake to respect the right of the child to preserve his or her identity, including nationality, name and family relations as recognised by law without unlawful interference. Furthermore, article 8 (2) stipulates that States shall ensure the implementation of these rights following their national law and their obligations under the relevant international instruments in this field, in particular where the child would otherwise be stateless.

Moreover, pursuant to article 11 of the CRC and the United Nations (UN) Key Principles for the Protection, Repatriation, Prosecution, Rehabilitation and Reintegration of Women and Children with Links to UN Listed Terrorist Groups, Indonesia is obliged to facilitate the return of these children from Syria. It stipulates that every child has the right to return to his or her own country.

Most importantly, the decision as to whether a child associated with a terrorist group should be repatriated has to be guided by the best interests of the child. Within this context, repatriation is necessary as these children are in danger of statelessness and deprivation of their basic rights. Therefore, the Indonesian government must guarantee that they will not revoke these children’s nationality and shall conduct the extraction of these children in dangerous conflict zones so they may receive adequate rehabilitation and reintegration.

Related articles: