Two decades since its independence, Indonesia experienced one of its darkest chapters of the nation’s 72-year history. While some justified it as an act of nationalism, many others are still haunted by the memory till today.

In 1965, Indonesian politics headed down a much darker path. Led by Kusno Sosrodihardjo – better known as Sukarno – Indonesia’s first appointed president, the government was infiltrated by communists and their sympathisers. Former president Sukarno, who led the autocratic Guided Democracy policy, drew unwanted attention from the UN (United Nations) for not acknowledging Malaysia as an independent country. He was also being closely monitored by the US (United States) for accepting aid from the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China – two of the largest communist countries of that era.

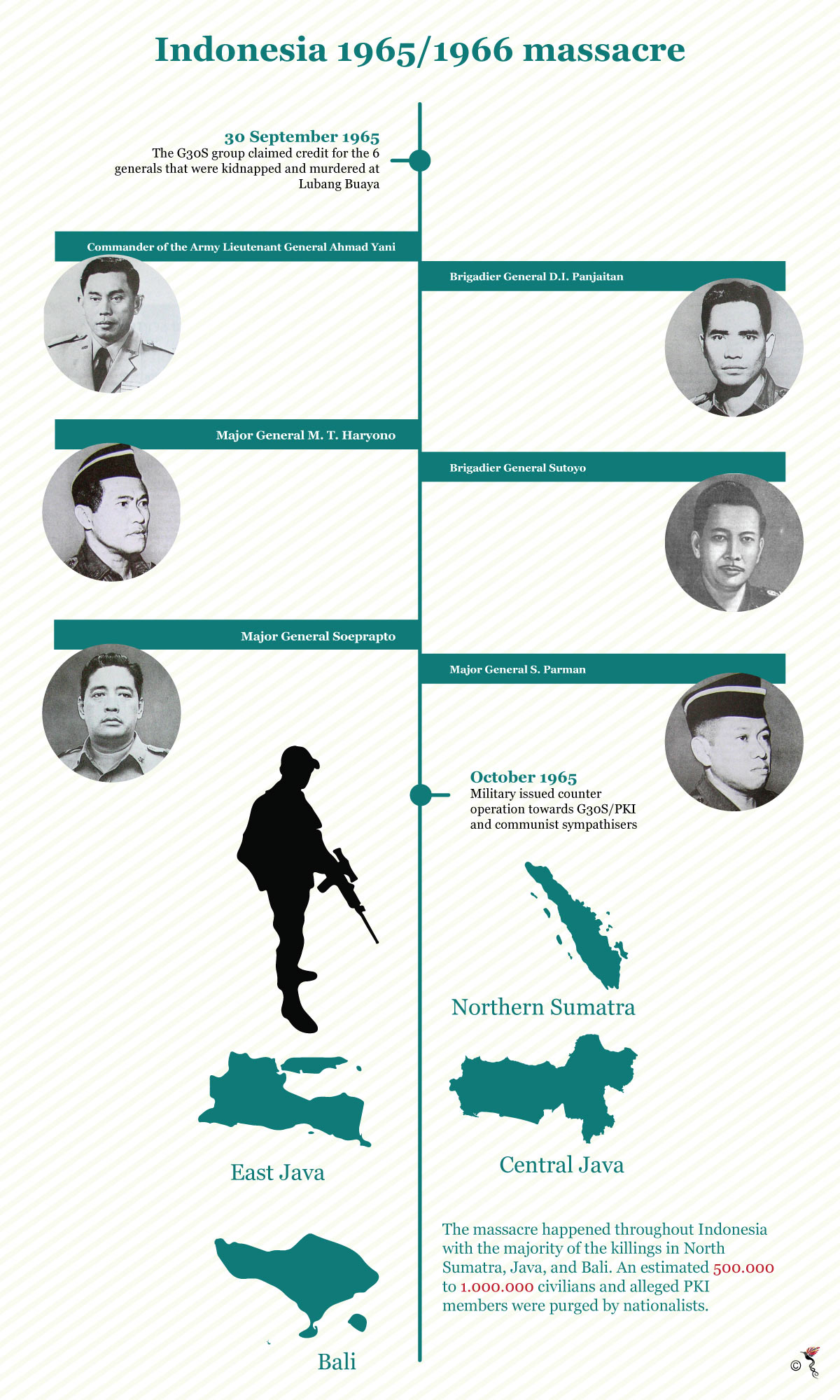

What truly happened on the eve of October 1, 1965 still remains a mystery that divides Indonesians till this very day. However, it was evident that the coupe attempt on the president, the kidnapping of six generals who were slaughtered at the "Lubang Buaya" (Crocodile’s Pit) and the pogrom that ensued, left a lasting memory in each and every Indonesian who lived through that dark age. The "Lubang Buaya" is located in the outskirts of Jakarta (the capital city of Indonesia), close to the Halim Perdanakusumah Air Force Base. After they were killed, the corpses of the six generals were then left in the "Lubang Buaya".

A brief history of the darkest age in Indonesian history.

Following the murder of the six generals, Major General Suharto who was the chief of Indonesia’s Army Strategic Reserve Command, ordered a counter operation to eradicate the 30th September Movement (G30S/PKI) – a self-proclaimed organisation who murdered the generals. Records of the murder showed that the generals were killed in a secret military-styled execution.

Through the combined efforts of Suharto, the nationalists and radical religious organisations, the propaganda against the PKI (The Communist Party of Indonesia) was spread throughout the archipelagic nation.

Associate Professor from the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at Melbourne University, Katherine McGregor replied The ASEAN Post through an email when asked about the effects that the 1965/1966 killings had on the identity of Indonesia.

“The killings and mass violence brought through a reorientation to the Indonesian society, which included a shift from mass political mobilisation and firm anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist critique in almost every aspect of society to a new emphasis on developmentalism based on anti-communism and support for capitalism,” she stated.

Mcgregor added that the anti-communist ideology which still exists among Indonesians today showed how powerful the reorientation was.

Sukarno was impeached a year later on grounds of tolerating the G30S/PKI and the communist agenda. He neglected the country’s economy and promoted “moral degradation” with his womanising behaviour. During his trial, Sukarno referred the murder of the generals as a “ripple in the sea of the revolution.”

Subsequently, the killings were wiped out from history books during Suharto’s three-decade long hard-line regime. However, some evidences survived the purge, which were then immortalised through a motion picture named Penghianatan G30S/PKI (The Betrayal of G30S/PKI), the Museum of PKI Treason and a monument that was erected to honour the fallen generals.

“The destruction of the Communist Party was a pivotal event in Indonesian history,” Robert Cribb, a linguist and historian from the Department of Political and Social Change at the Australian National University said when contacted by The ASEAN Post.

In his article titled “Unresolved Problems”, Cribb wrote that Suharto “took steps to consolidate the already widespread public presumption that the PKI had masterminded the coup.” He added that the New Order killed many more people than it needed to, in order to secure its future. The New Order could still have been in place with a less repressive apparatus.

While there is a handful who felt remorse, a majority of the paramilitary organisation members and civilians involved in the killings of the PKI members and their affiliates consider their actions as an act of nationalism because they were not prosecuted.

Reports describing the massacre were only uncovered after Suharto and his New Order had fallen in 1998. The topic had been a taboo during his 32-year rule. The survivors of the massacre and those affected by the 1965/1966 tragedy have yet to reach closure till today.

“At least the current Indonesian state have to acknowledged that this tragedy happened, revoke all regulations that discriminates former PKI political prisoners and the government rhetoric should focus on building peace, dialogue, and reconciliation between related stakeholders and thinking in preventing another tragedy with this unprecedented scale to ever happen again in Indonesia,” Yosef Djakababa, the Director and co-founder of the CSEAS-I (Centre for Southeast Asian Studies for Indonesia) told The ASEAN Post when asked about the reopening of the G30S/PKI case in Indonesia.

However, McGregor also added that despite his election promise to address human rights violations, current Indonesian President Joko Widodo – better known as Jokowi – has personally remained very quiet on this issue.

“If Jokowi came out forcefully and said he would reopen it perhaps by pressuring the attorney general to investigate further as per the 2012 KOMNASHAM recommendation then it would probably result in more backlash and outcry.”