In May last year, two men were flogged 83 times in the Indonesian province of Aceh in front of a crowd of thousands. Their crime – being gay.

The two men were apprehended a few months back for allegedly having same sex relations and a Sharia court later convicted them of sodomy. Aceh is the only Indonesian province to enforce strict Islamic law for criminal offences. While the Sharia courts in Aceh have enforced public floggings before, this was the first time it had sentenced people to be flogged for same-sex conduct.

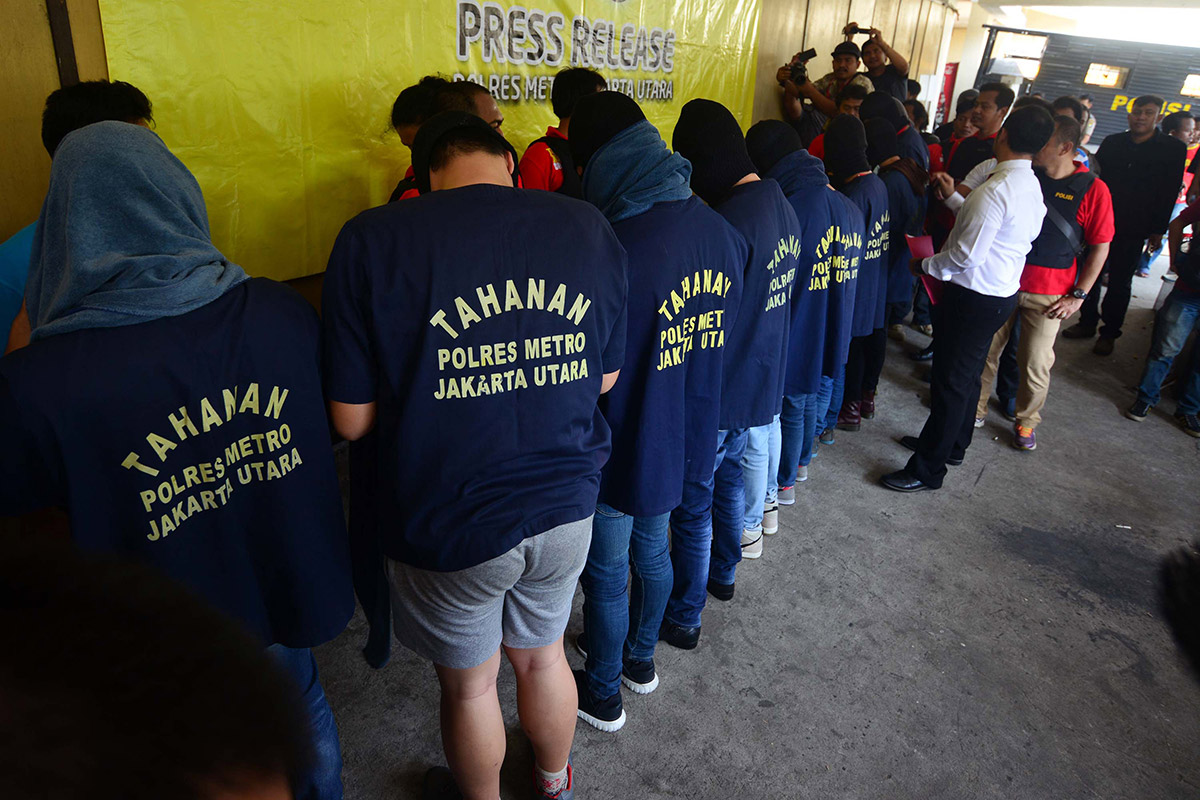

This is just one of many incidences of anti-LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) crackdowns in Muslim majority Indonesia. According to a report by Human Rights Watch (HRW), the anti-gay hysteria has sparked a HIV epidemic which has become a serious public health concern.

Moral panic

The origins of this anti-LGBT “moral panic” can be traced back to early 2016 where strong sentiments against the LGBT segment of society reverberated throughout the echo chambers of Indonesian society. The National Child Protection Commission issued a decree, decrying “gay propaganda” and called for stronger censorship to be put in place. A national level psychiatric association proclaimed that those with same-sex sexual orientations and transgenders had succumbed to “mental illnesses.”

A 2016 opinion poll discovered that 26 percent of Indonesians disliked LGBT people – making them the most disliked group in the country. A similar poll conducted in 2017 revealed that more Indonesians feared the LGBT community as opposed to those who knew what the acronym stood for.

Indonesia’s defence minister labelled LGBT rights activism a proxy war on the country, led by outsiders. He was quoted as saying that since the LGBT community were “demanding more freedom,” it would constitute a “threat” to the nation.

Rampant cases of HIV

This discrimination has been found to have fuelled a HIV epidemic throughout the country.

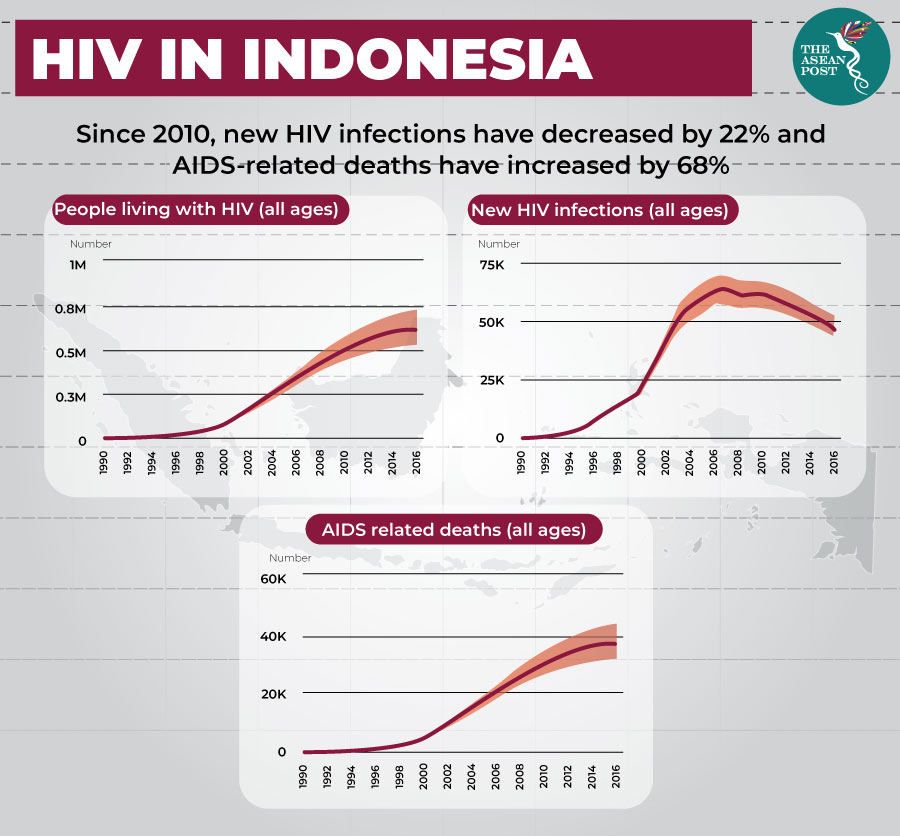

At nearly 48,000 new infections a year, Indonesia has been categorised by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) as one of the nine countries among 186 that has seen a worrying rise in HIV related cases. Data from UNAIDS revealed that the country recorded 46,357 new HIV infections in 2017. Of that number, 33 percent were non-key affected population females, 24.5 percent were male clients of sex workers and 23.5 percent were men who have sex with other men (MSM).

Although most new HIV infections are through heterosexual transmission, one third of new infections occur among MSM. Public data indicate that the percentage of MSM infected with HIV has increased fivefold from five percent to 25 percent between 2007 and 2015. In urban centres like Denpasar and Jakarta, the situation is even worse – with nearly one in three MSM infected with HIV. Besides that, HIV prevalence amongst transgender women is reportedly at 22 percent in 2011 and 2015.

Economic impact

Although outreach programs by non-governmental organisations (NGO) have made some headway, there is still much to be done. Among the many impediments to containing the Indonesian HIV epidemic include limited public attention on the matter, weak government policies as well as limited financial resources. Jakarta cannot afford to let the problem fester any longer as it could lead to various social issues as well as have an adverse effect on the economy as a whole.

Depending on which sector of the economy, the HIV epidemic could slow or reverse growth in the supply of labour. Relatedly, the government would end up spending more on health instead of diverting financial resources which could be used to improve human capital. Over time, it could lead to slower gross domestic product (GDP) growth and turn investors away if they are convinced that the epidemic could harm their returns on investment.

Besides that, the epidemic may deepen poverty in already poor areas of Indonesia. The worst hit provinces in Indonesia, West Papua and Papua are incidentally some of the more poorer parts of the country. Moreover, the savings of poor families could be hard hit owing to the increase in HIV-related health expenses. This in turn, could further impoverish them and cause long-term damage to their well-being, society and the overall economy.

To correct this detrimental course that Jakarta is currently on, genuine efforts must be made by the government to repair the damage afflicted on the LGBT community there. Indonesian society must do away with hateful rhetoric aimed towards that segment of society for the greater good of its people and the country.