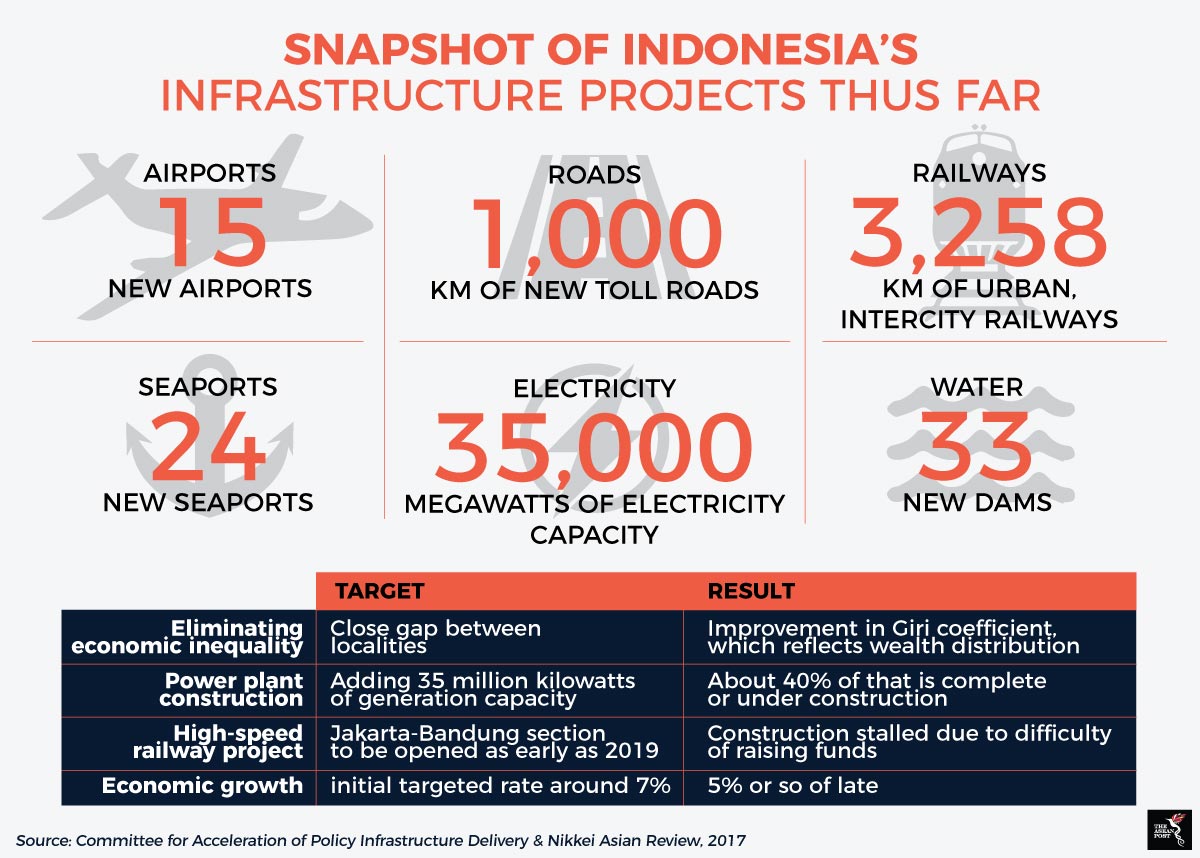

When Indonesian president Joko Widodo was elected in 2014, he vowed to boost economic growth to 7% of gross domestic product (GDP). Subsequently, plans to spend around US$355 billion building a total of 265 projects by 2019 were announced, in a bid to bridge the US$1.5 trillion infrastructure gap Indonesia still had in comparison to other emerging economies, according to the World Bank in 2017.

“Infrastructure development in Indonesia has been neglected in the past,” Rini Soemarno, minister of Indonesia’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) told the Nikkei Asian Review in November 2017.

Inadequate resources

Heavy investments into infrastructure have not proven as promising as Widodo has hoped for. In the first place, funding for these investments was inadequate. Despite initially projecting that 37% of financing for these infrastructure projects would be sourced from private companies, Widodo’s administration currently still relies on SOEs to fund four-fifths of these infrastructure projects.

Most private equity investors could not justify the low profitability of such contracts, Johannes Suriadjaja, chief executive of private construction firm, Surya Semesta Internusa explained to Reuters in October 2017.

Holding on to a majority of these projects means that the state continues to shoulder most of the financial risks. Yet, this is already a better option than depending on overseas borrowings. Widodo has a tight fiscal budget to manage, since he cannot exceed 3% of budget deficits under Indonesian law.

Initial measures to add to the government’s coffers such as the scrapping of gasoline and fuel subsidies in 2015 have not been enough. Bloomberg reported in January 2018 that Widodo was still chasing for US$150 billion to fund his projects. The state budget has contributed just US$15 billion so far.

The result is that by October 2017, only 26 projects have been completed since construction began in 2016. According to documents sighted by Bloomberg, around 145 projects remain under construction. At present, the only projects still with the potential to be completed by April 2019 are the highways and regional ports, according to the Nikkei Asian Review in a separate analysis.

Further delays in these infrastructure projects could also adversely impact the finances of state-owned enterprises, which are already shouldering substantial debt. The debt levels of both, the majority state-owned toll operator, Jasa Marga and state-owned contractor, Wakita have risen since they obtained funds from capital markets and banks, the Nikkei Asian Review had earlier reported.

A lack of skilled labour, coupled with the infrastructure rush does not help. A slew of 14 construction accidents took place over the last six months, according to Dradjat Hoedajanto, chairman of the Indonesian Society of Civil & Structural Engineers.

A 15th, involving the fall of part of the formwork for a pier on several people resulted in a total ban by the Indonesian government on the construction of all elevated infrastructure in February 2018.

Opposition party leaders had earlier slammed Widodo’s “election-oriented deadlines” as unfeasible due to a lack of skilled labour. Out of Indonesia’s 8.1 million-strong labour force, only 10% have proper certification, according to follow-up reporting by the Nikkei Asian Review in February 2018.

"Human resources in the construction sector are probably not well-prepared to do so many jobs and have to complete them within such a short time," explained Dradjat Hoedajanto, after the suspension was placed on all elevated infrastructure construction.

Analysts further noted that Indonesia’s economic growth has not gone beyond the 5% mark since 2014. In the meantime, Indonesians have had to deal with increased traffic congestion amidst the tangle of ongoing construction projects pervading many sidewalks and roads.

“We are trapped whichever way we go,” said Dati Wijayanti, who needs to leave Bogor, where she lives, before dawn in order to reach her office in central Jakarta in less than two and a half hours.

Now that construction of these projects has already started, further delays could prove even more costly. With the latest ban on elevated infrastructure construction, Widodo’s infrastructure plans may have finally slowed down for a while, but it may not be so for long, or the whole slew of projects could tumble down like a house of cards.

Economic realities may prove to be less than kind to Indonesian president Widodo’s political ambitions, but this is a small cost to pay compared to what Indonesians have to live with, whether the incumbent president of Indonesia gets re-elected or not.