Thailand’s election is mere weeks away and regardless of who ends up the victor, developments throughout the period of the military junta’s rule since 2014 should provide several lessons for the country’s future leader. An issue that seems to have been gaining even more traction as the election date nears - and one that any future Thai leader worth his or her salt should be worried about - is the simmering religious intolerance between Buddhist and Muslim Thais.

The reason the elections has brought this matter to the fore is due to the emergence of the Pandin Dharma Party (Land of Buddhist Teaching) that intends to contest the 24 March election. The Pandin Dharma Party brings to voters the message that “Buddhism is under threat”.

While the party does not directly attack Islam and rejects the accusation of being anti-Muslim, it does accuse secular authorities of harassing Buddhist monks and of caring more about Thailand’s tiny Muslim minority than the religion followed by more than 90 percent of Thais.

“Monks have been dealt with heavy-handedly by the state,” complains former monk Korn Medee, 47, leader of the party. “The government has overtly favoured the other religion over Buddhism,” he told international media.

Last month, on 13 February, the Crime Suppression Division (CSD) of the Thai Royal Police announced the arrest of 18 Buddhist monks accused in connection with various crimes, including murder and sexual harassment in the latest operation to clean up the country’s Buddhist institutions. A day later, the police added the abbot of a temple in Suphan Buri (capital of the homonymous province in central Thailand) to its list of criminal suspects.

CSD chief General Chiraphop Phuridet vowed to make 2019 a year of "sweeping temples clean".

Insurgency

The South Thailand insurgency is an ongoing conflict centred in southern Thailand. It began in 1948 as an ethnic and religious separatist insurgency in the historical Malay Patani Region, made up of the three southernmost provinces of Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat as well as neighbouring parts of Songkhla Province.

Some have argued that it is this insurgency that ignited religious tensions between the Buddhists and Muslims. Meanwhile, separatist groups in South Thailand have maintained that all they are asking for is to hold on to their identities instead of having to adhere to Thailand’s assimilation process. Religion still has very little to do with the insurgency.

Nonetheless, last year, regional media quoted Buddhist monks as saying that Buddhists and Muslims in the South had lived together peacefully in the past but things have now changed.

Head monk of Muang district in Yala, Phra Rachamonkol Wuttajarn, told the media that in the past, people of different faiths helped each other even on religious-related matters but now they have taken a different attitude.

"Some see Buddhists as victims and interpret events linking the violence to Islam. Or they think that Muslims gave their support to those behind the violence. People have lost trust," he said.

In October, a report surfaced of a mosque in Bangkok - in existence for more than 100 years - which had become the subject of many anonymous complaints about the loud daily prayers conducted there.

Sombat Wongsamai, a 68-year-old adviser to the Imam (prayer leader) of Bang Uthit Mosque in Bang Khao Laem district, said the mosque, in response to the complaints, had lowered the volume of its loudspeakers, but complaints have not stopped.

The Bang Khao Laem District Office apparently received complaints about the mosque too and sent officials there several times to check the volume levels of the loudspeakers used for daily prayer gatherings. “But every time measurements are made, the mosque is found to have complied with noise standards and the volume has never exceeded 80 decibels,” Sombat said.

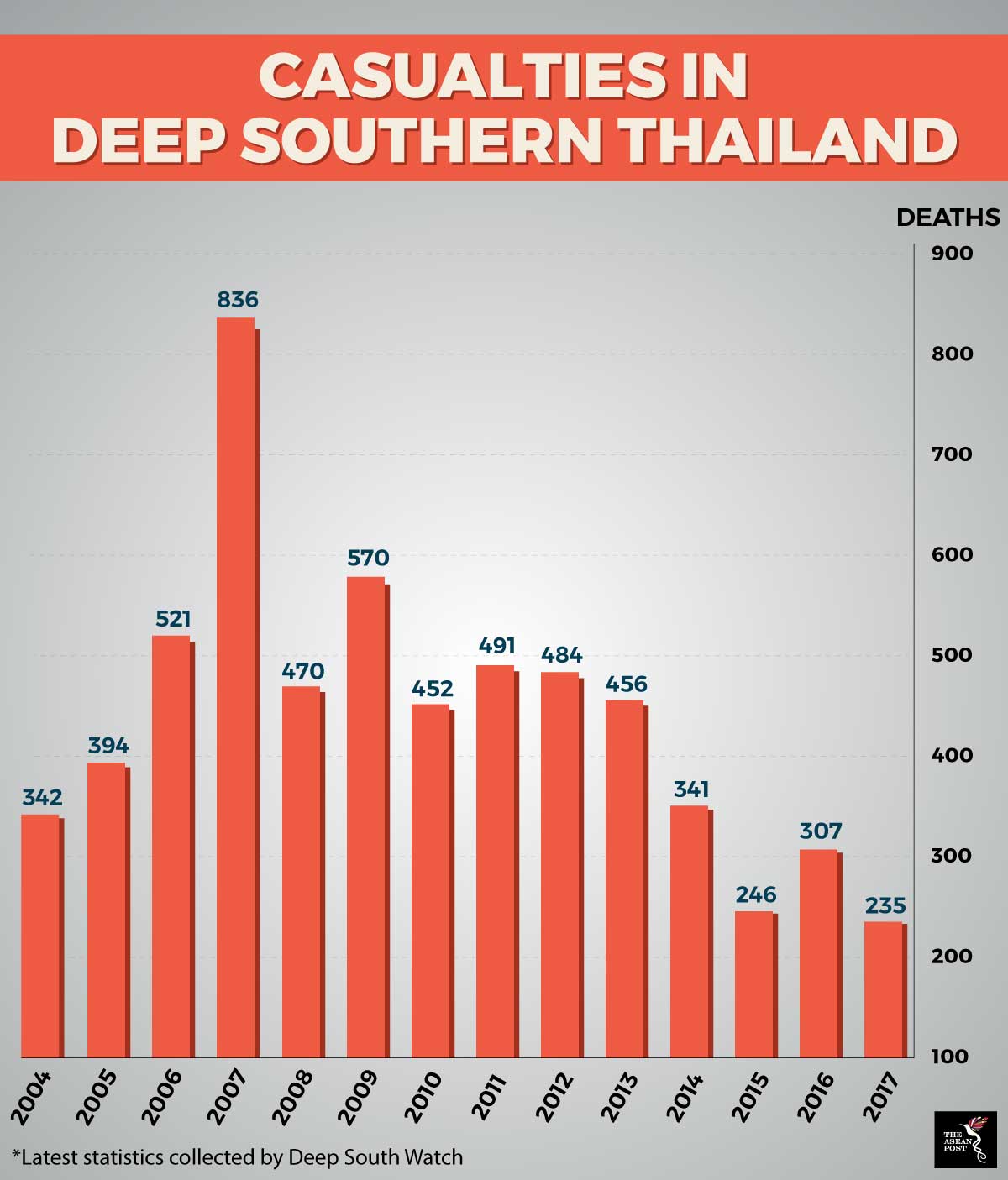

According to the latest 2017 statistics from Deep South Watch, violence has reached an all-time low. However, it is also worth noting that despite a drop, the violence – previously contained within the deep South – seems to have spread to other parts of Thailand as well.

In August 2016, two blasts struck Patong beach on the island of Phuket while three more explosions were reported further South - two in the southern town of Surat Thani, killing one, and another blast in Trang, which also left one person dead. Two more explosions also occurred in southern Phang Nga province. A military source told the media on condition of anonymity that he considered the August bombings to be an expansion of the insurgency, partly as a test for new recruits.

While experts agree that the Pandin Dharma Party’s chances to make a significant impact in the upcoming elections is slim, that’s not the point. The point is that the reason such a party exists is more than likely because there is a growing level of intolerance between Buddhist and Muslim Thais. This intolerance is possibly linked to the insurgency.

So far, it has been customary for the Thai government to brush aside the ongoing deep south insurgency. But perhaps it’s now time that the Thai government – regardless of who emerges victorious after 24 March – to seriously address the decades-long insurgency before it explodes into something uglier.

Related articles: