Over the past decade, renewable energy investments in Southeast Asia have been fluctuating substantially, mainly influenced by the completion of large-scale projects and changes in the overall policy landscape.

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), nearly US$27 billion was cumulatively invested in the region between 2006 and 2016. Thailand attracted the bulk of this sum, with upwards of US$10 billion, representing 40 percent of the total investment. This was followed by Indonesia and Philippines which accounted for 20 percent each of the total cumulative investment.

Nevertheless, scaling up renewable energy investments in the region will require substantial effort when addressing investment barriers. If the region is to reach the aspirational target of 23 percent primary energy from renewable energy by 2025, countries must improve their financial services in order to woo potential investors.

Addressing the challenges

The risk associated with the investment landscape differs from country to country within the region. Mature markets like Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines rely more on local commercial banks compared to frontier economies like Cambodia, Lao PDR and Myanmar (CLM). The latter rely more on public institutions like traditional donor and development banks, to fund their infrastructure investments.

As such, the strategy that should be employed is one which leverages on the extent of which the country has developed its renewable energy financing. The best way of doing so is via blended finance which has already been employed in some parts of the world including Southeast Asia. It has helped unlock and attract more foreign and domestic capital investment in renewable energy assets.

By definition, blended finance refers to the mobilisation of additional private capital using public or philanthropic funds such as foundations. According to a working paper published by the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) in January this year, blended finance is “essential to increase private investment in critical markets”.

Blended finance instruments often transfer risks of a private sector investor to the public sector –including political risks, technical risks and commercial risks. The different tools used to transfer these risks include insurance as well as guarantees and hedging instruments like swaps and derivatives. Each of these instrument types address different risks and barriers.

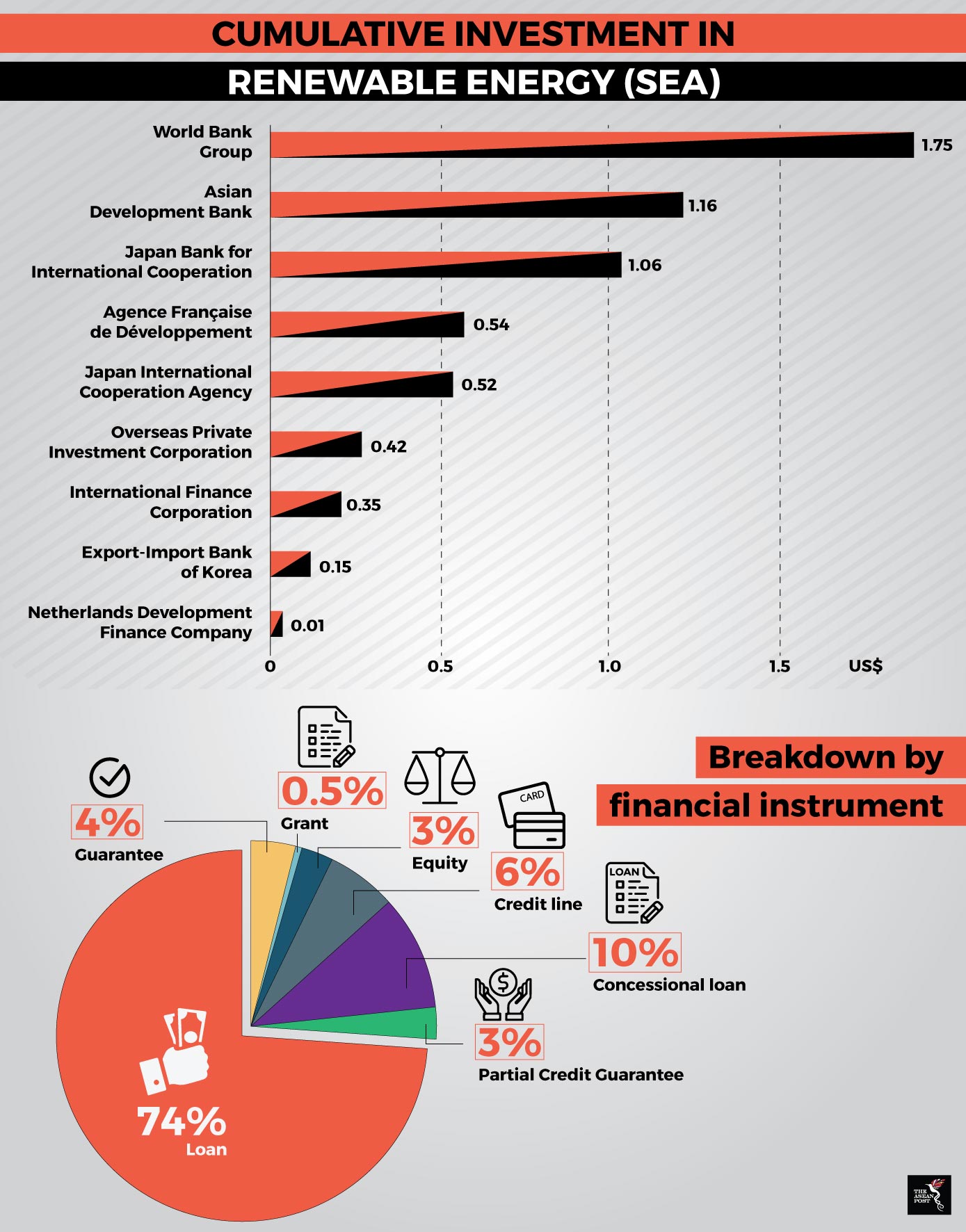

Source: International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA)

So far, steps have been taken in the right direction towards deploying blended financing in Southeast Asia. Development finance institutions (DFI) like the Asian Development Bank (ADB) have established funds to catalyse projects around the region. ADB’s Leading Asia's Private Sector Infrastructure Fund (LEAP) established in March 2016 is one such initiative. The fund is an infrastructure co-financing fund aimed at filling financing gaps and increasing access to finance for infrastructure projects in the region.

Another use of blended finance is the utilisation of public finance to mobilise private investment through risk mitigation or credit enhancement. One example is a guarantee facility by GuarantCo worth US$13.5 million to support the Thai Biogas Energy Company’s (TBEC’s) four wastewater-to-biogas plants in rural Thailand. Using this credit enhancement facility, TBEC then used the guarantee to obtain a US$13 million loan from the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) to construct two additional plants and move forward with expansion plans to other developing areas in the Lower Mekong region.

Another form of blended finance is public-private partnerships (PPP) which combines the potential, skills and resources of both, public and private sectors. Such PPPs help facilitate risk sharing, develop larger projects and improve stakeholder understanding of technical solutions and related risks. For example, in Cambodia, solar PPP investments have enhanced overall awareness and capacity in the sector. Sunseap, a solar developer entered into a 20-year solar PPA with Electricite Du Cambodge – Cambodia’s state-run utility – which was also co-financed by the ADB.

Challenges remain

Nevertheless, there are financial access challenges that have the potential to drive away private-sector capital investors. These challenges include unfavourable renewable energy project scale, weak local financial markets to refinance or exit from a project, knowledge and capacity gaps among project stakeholders and investment risks.

Access to affordable capital for such projects can be a monumental challenge as the scale of these investments is usually small with substantial transaction costs. Consequently, investors become less interested in renewable energy investments as opposed to traditional infrastructure investments. This is most prevalent in CLM economies.

Another problem is the lack of private equity funding due to investor fears of improper market structures. Currency inconvertibility risk, power off-taker risk and the lack of available risk mitigation instruments are challenges that need to be swiftly addressed. In some countries, there is a persistent lack of access to bank debt which drives up the costs associated with debt finance. Moreover, the limited length of loan tenures can become an issue as well.

In addition, a majority of local financial institutions often have insufficient awareness due to limited technical knowhow. Most banks are more experienced when dealing with fossil fuels and many aren’t confident enough to risk jumping into a renewable energy investment. Besides that, from the viewpoint of a commercial bank, limited local benchmark and reference projects also reduce their desire to invest.