The trial of two former Radio Free Asia (RFA) journalists in Cambodia on charges of espionage tomorrow promises to be a closely-watched affair.

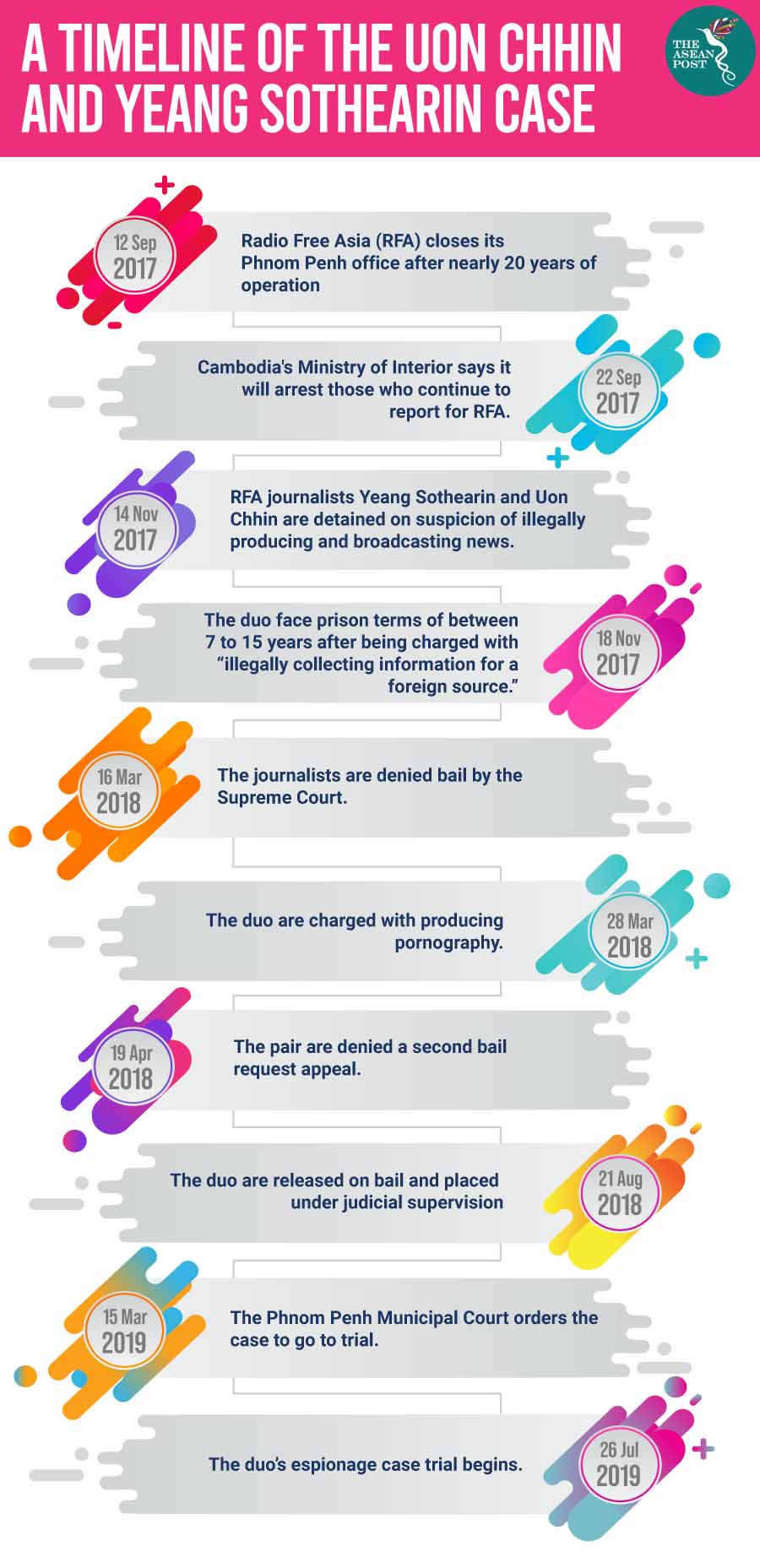

RFA’s former Phnom Penh bureau office manager Yeang Sothearin and former videographer Uon Chhin were arrested in November 2017 after Cambodian police found recording and broadcasting equipment in a hotel room they raided, this coming two months after the United States (US)-based RFA shut down its Phnom Penh office citing government pressure on independent media.

Despite the pair explaining that the equipment was for a karaoke business they were planning on opening, and the police unable to find any evidence that it was used to broadcast news back to RFA’s headquarters in the US, the duo are looking at seven to 15 years in prison after being charged with “illegally collecting information for a foreign source" under Article 445 of Cambodia's Criminal Code – effectively implying they were spies.

The duo were held in pre-trial detention for more than nine months before being released on bail last August on the condition they check in with local police monthly. With their passports and equipment confiscated, Yeang and Uon are the latest in a string of Cambodian journalists, activists and opposition members to face persecution.

Internationally, the case has gained widespread attention with Human Rights Watch, the Committee to Protect Journalists and even the United Nations (UN) condemning the duo’s detention and charges laid against them.

Within Cambodia, the duo’s plight has been publicly supported by more than three dozen journalists, who in January published an open letter urging the Phnom Penh Municipal Court to drop all charges against the two as they “intimidate other reporters who are trying to do their work and will negatively impact the freedom of the press in Cambodia as well.”

Then again, press freedom is not one of Cambodia’s strong points.

‘No basis for the ludicrous charges’

Cambodia is 143rd in the 2019 World Press Freedom Index – an annual list compiled by France’s Reporters Without Borders which measures pluralism, media independence, transparency and self-censorship in 180 countries.

RFA closed its Phnom Penh office on 12 September 2017 after nearly 20 years of operations in Cambodia due to the “relentless crackdown by Prime Minister Hun Sen's authoritarian regime on independent media ahead of critical polls next year”. 10 days later, Cambodia’s Ministry of Interior said it would arrest any former RFA journalists who continue to report for RFA.

The US Congress-backed RFA has a history of reporting on topics such as human rights, corruption, illegal logging, land rights violations and other social and labour issues in Cambodia – all sensitive subjects for the government, especially before last July’s key national elections.

The crackdown ahead of the election – in which Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party unsurprisingly took all parliamentary seats on offer – also saw authorities order the closure of 32 radio frequencies across 20 provinces, including stations that relayed independent Khmer language news broadcast by three American outlets – RFA, Voice of America, and Voice of Democracy. The pro-democracy Cambodia Daily was forced to close and a key figure in the independent press, The Phnom Penh Post, was bought by a Malaysian businessman with close ties to the Cambodian government.

“The two former RFA journalists are victims of Prime Minister Hun Sen’s unending attack on media outlets that dare air critical reports about the government,” noted Human Rights Watch’s Asia director Brad Adams last month. “There’s no basis for the ludicrous charges against these two reporters or for forcing them into judicial supervision. The court should drop both the charges and supervision arrangements immediately.”

While the charges have most certainly not been dropped, what may be is the European Union’s (EU) Everything But Arms (EBA) trade agreement with Cambodia. Providing products from the world’s least developed countries with tax-free access to vital EU markets, the trade scheme is currently in a six-month monitoring period in Cambodia due to the country’s poor record on human rights and democracy. Although Prime Minister Hun Sen has remained defiant in the face of these sanctions, EBA removal would undoubtedly be a huge blow to Cambodia’s economy – especially its garment and footwear sectors which are the country’s largest employers.

Whatever the outcome of tomorrow’s trial, RFA President Libby Liu’s comments on the day RFA shut down its Phnom Penh office nearly two years ago still rings true.

"As history has shown, dictators may rise and force their will on nations, but the people will always seek truth in pursuit of freedom."

What little consolation that may be for Yeang and Uon, though, remains to be seen.

Related articles:

Cambodia opposition leader released