Malaysia’s indigenous peoples comprise over 67 ethnic groups, representing around 14 percent of the country’s population. While they live in almost every state and territory within the country and are afforded special status by the constitution, indigenous people often suffer from poverty and social exclusion.

Despite socio-economic limitations, the indigenous people of Malaysia seem to be saddled with the responsibility of having to fight for the survival of the country’s forested areas. Indigenous groups and defenders of indigenous land are at the frontline of forest conservation. This has exposed them to the increased risk of harassment, intimidation, arrests and even death.

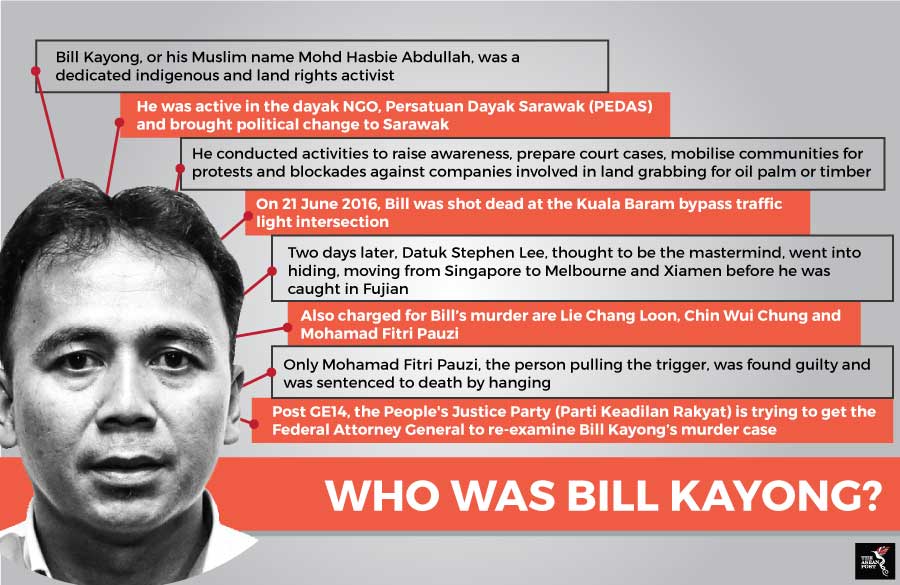

According to a report by Amnesty International on the struggle to defend Malaysia’s indigenous land released this week, this threat is made possible by the absence of government protection and the culture of impunity that sides with transgressors. The report highlighted the emblematic death of Bill Kayong - a grassroots activist working to mobilise Dayak communities in Bekelit who are facing a land dispute - who was shot dead in the city of Miri, in the state of Sarawak in June 2016.

Blood spilled for ancestral land

“Bill’s death is the only case Amnesty International documented in which a person has been held accountable for the threats, intimidation and violence committed by individuals described as “gangsters” against members of indigenous communities defending their right to land, or those helping them. In this case, however, only one person – the man believed to have pulled the trigger – has faced proper trial. Those who gave the orders for the attack are believed to remain at large,” the report stated.

Source: Various sources.

According to Amnesty International, while most other Malaysians have profited from the country’s growth, the first people to inhabit the land faced encroachment and are prevented from benefiting from their traditional sources of livelihood as a result of the development. This has left them exposed to poverty and further marginalisation.

“In the worst cases, they have been summarily dispossessed of their lands, forced from their homes, and made to witness the depletion and degradation of natural resources they lay claim to. The main reason for this is the lack of recognition and implementation of indigenous peoples’ rights to land in law, policy and practice. While the Malaysian Federal Constitution provides for the right to property and some recognition of indigenous land, in reality, there is a lack of realisation of these provisions,” stated Amnesty International.

More intact forests in indigenous regions

Globally, there are around 370 million people who recognise themselves as indigenous, with many of them having strong and steadfast spiritual and cultural relationships with their land. For the indigenous, the concept of land and territories has many dimensions vital to their collective identity. Their connection to land goes beyond heritage and ways of life, to a lifeline for food, medicine and survival, as well as a major cause of struggle and death. The disappearance of forests could spell the death knell to indigenous cultures.

According to a global spatial overview of indigenous lands and conservation by Nature Sustainability journal in July this year, collectively, the various group of indigenous people manage or have tenure rights over at least 37.9 million square kilometres or 28.1 percent in 87 countries or politically distinct areas. The overview provided more evidence to the growing narrative and recognition that indigenous rights to land and stewardship are key to local and global conservation goals.

“A higher proportion or 67 percent of indigenous peoples’ lands was classified as natural compared with 44 percent of other lands. Consistent with this, most parts of the planet managed and/or owned by indigenous peoples have low-intensity land uses,” stated the authors of the overview.

Based on information compiled from 127 data sources from around the world, the overview found that land where indigenous people retain substantial influence over decision making on use, development and care of land resources, are many of the world’s most sparsely populated, intact places.

In Malaysia and many other countries in the region and around the world that are home to indigenous groups, it is not the lack of real will on the ground that is threatening the survival of forested areas and diverse biodiversity. Instead, the blame lies with a lack of will at the top and the general population who simply choose not to listen.

Related articles:

Indigenous people: The struggle for home

Developing an appetite for whale conservation