Late in March, a Malaysian non-governmental organisation called Malaysians Against Pornography (MAP) made a startling discovery regarding pornography consumption among children in Malaysia. While pornography is typically meant for those aged 18 and above, MAP’s survey found that in 2018, 80 percent of Malaysian children aged 10 to 17 years have watched pornography intentionally. On top of that, almost 89 per cent of children aged 13 to 17 were victims of online grooming.

Speaking on the survey’s findings, Malaysia’s Deputy Prime Minister Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, who is also the Women, Family and Community Development Minister, said that while the findings were indeed shocking, she urged MAP to clarify how it came to such a conclusion.

“Obviously the result is something worrying. Nonetheless, the findings should be explained in terms of how the study was conducted, how small or how big was the sample (group)? How did MAP come to that conclusion? How did MAP get the results?” she said.

Malaysia, however, is no stranger when it comes to the notoriety involving children and pornography. Early last year, most of the local media quoted Assistant Commissioner Ong Chin Lan of the Royal Malaysia Police's Sexual, Women and Child Investigation Division (D11), who revealed in a seminar on "Cyber Protection for Children" that Malaysia has the highest number of IP addresses uploading and downloading photographs and visuals of child pornography in Southeast Asia.

According to data furnished by Dutch police based in Malaysia in 2015, about 17,338 IP addresses involved in child pornography were from Malaysia. Moreover, Ong said data showed that prior to 2014, an average of 60 children a year were sexually assaulted by perpetrators whom they had befriended through the Internet. The figure increased to 184 in 2015 and 183 in 2016. In 2017, the figure was 117, as of May 2017.

Lack of faith

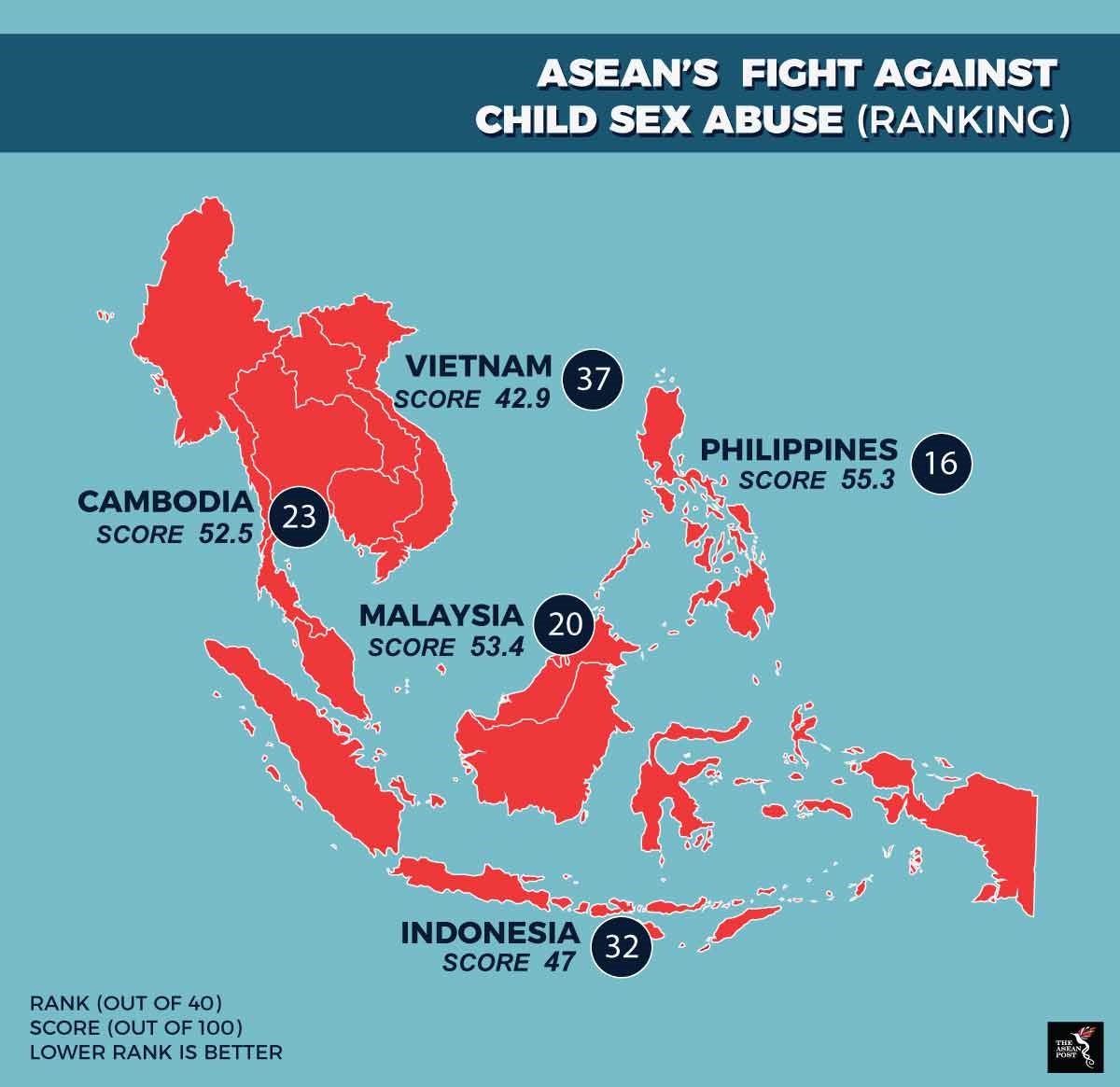

While Malaysia has put in place several initiatives to combat the sexual abuse of children, Malaysians do not seem to believe that it’s enough. According to a report by The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) in January, the perception is that ASEAN as a whole is suffering in terms of improving its poor record of child sex abuse and exploitation, and while Malaysia is seen as one of the better ASEAN countries in terms of prevention, in the scheme of things, that isn’t saying very much.

The EIU report, titled Out of the Shadows: Shining light on the response to child sexual abuse and exploitation, surveyed 40 countries in total and had a point system based on a weighted average of four indicators: environment, legal framework, government commitment and capacity and engagement of civil society, industry and media. The scores each country received was based on the perception of the people of that country.

While Malaysia ranked second place in ASEAN after the Philippines, globally, it only ranked 20 with a dismal score of 53.4 points. While the survey does not claim to present the scale of the problem in each country nor its prevalence, the fact that Malaysians have little faith in the country’s ability to combat child sex abuse does ring alarm bells, nonetheless.

Malaysia scored particularly low on “government commitment and capacity”, ranking 33 out of the 40 countries with a score of 39.3.

As of 2017, Malaysia passed the Sexual Offences Against Children Act 2017 which, among other things, includes a section on sexual grooming. The law received support on both sides of the political divide when it was first drafted, and since its inception has received high praise but the problem is far from over.

The Malaysian government has also attempted to block many pornographic sites. In fact, it was reported just last week that from 2015 to 2018, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) had blocked more than 400 websites containing child sexual abuse content through collaboration and information-sharing with the police and Interpol. But anyone who has even the slightest bit of knowledge about the Internet knows that these blocks can be easily bypassed.

The fact of the matter is that Malaysia must look at more stringent enforcement and effective prevention. Like many legal observers have often said “Malaysia has many good laws, but lacks enforcement”. It is hoped that “New Malaysia” will be different.

Related articles: