On the night of August 18, 2017 in Caloocan – the fourth most populous city in the Philippines – nineteen-year-old Carl Angelo Arnaiz appeared to have been kneeling on the ground before being mercilessly shot – four times in the chest and once in his right arm – by policemen who alleged that he returned fire whilst they were responding to a robbery call.

Two days earlier, seventeen-year-old Kian delos Santos was suspected of carrying drugs and was subsequently executed by the Caloocan policemen in similar fashion. His last words were “Please stop. Please stop. I have a test tomorrow.”

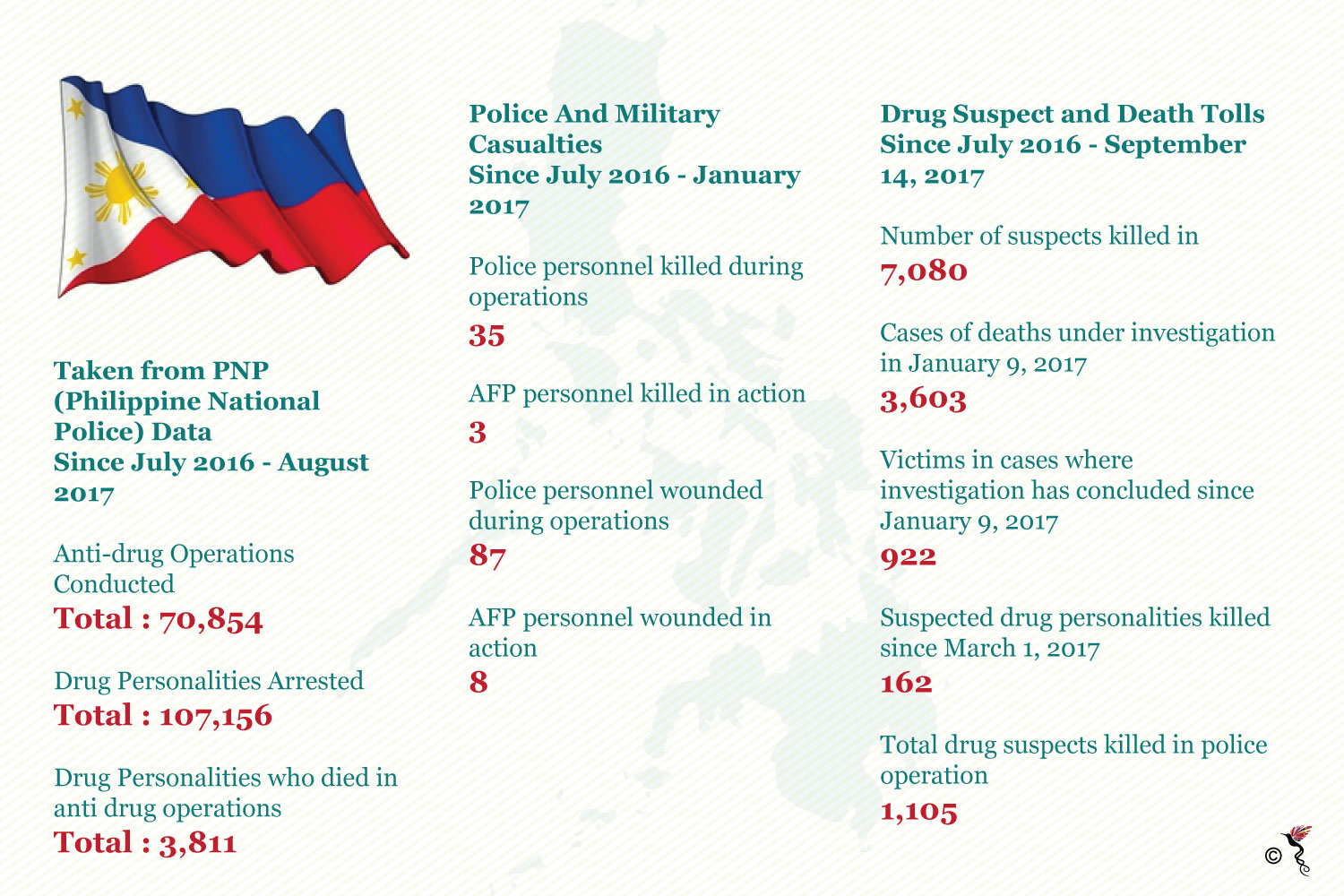

The two boys make up a tiny speck of the suspects killed in the Philippine war on drugs. For now, over 7,000 people have been reported killed.

The man behind this brutal campaign is none other than the President of the country, Rodrigo Roa Duterte.

Is the campaign bearing fruit?

According to the Executive Director of the Manila based Institute for Political and Electoral Reform, Ramon Casiple, in his email correspondence with The ASEAN Post, Duterte continues to enjoy support for his brutal anti-drug campaign because it “drove drug pushers and users from the street, lessened drug-related crimes and produced palpable confidence among citizens regarding peace and security in the neighbourhood.”

Crime rates have indeed dipped during Duterte’s first year in office. Compared to his predecessor, crime incidents decreased by more than 60,000 cases within the same period. Data from the PNP (Philippine National Police) also revealed that all crimes dropped by 9.8 percent but killings rose close to 23 percent.

Responding to this, the PNP Chief, Ronald dela Rosa attributed the spike in killings to the anti-drug efforts stating that previously, the numbers pointed to the killings of innocent civilians but now they are mostly drug personalities.

The Philippine polling body, Pulse Asia also reported in a survey that 82 percent of residents in the capital, Manila felt much safer thanks to the war on drugs.

Statistics on the Philippine drug war.

Getting to the crux of the problem

Casiple noted that while there may be support for the fatal campaign, “the outstanding exception are poor communities where the anti-drug campaign brought fear among poor families who are prone to arrests or police operations, including killings.”

The drug problem is one rooted in poverty which explains why a large portion of those slain in police raids are from the lower rungs of the economic ladder. According to the Dangerous Drugs Board, drug users in the country are mostly part of families that earn a monthly income of a meagre 205 dollars.

Speaking to The ASEAN Post from her office in Manila, Jacqueline Ann De Guia, the Director of the Public Affairs and Strategic Communications Office of the Philippine CHR (Commission on Human Rights) explained that the situation is as such because “there is a shortage in terms of livelihood and the drug trade is a lucrative business for those whom are otherwise unable to support their families.” She revealed that the republic has multiple drug entry points which makes it easier and cheaper for locals to obtain narcotics.

“The poor are targeted because it is easier for the police to infiltrate the places where they live when conducting their raids. Besides, most of them lack a firm understanding of the legal system which enables law enforcers to further exploit the situation, often times to deadly ends,” she added.

The Filipino love affair with strongmen

Duterte’s penchant for summary executions and extrajudicial killings of criminals induced waves of criticism from human rights organisations within and outside of the Philippines. He has personally denounced western notion of human rights and recently, lawmakers sided with him to defund the independent Philippine CHR. Nevertheless, the outspoken leader still rides high on a huge wave of support from his citizenry.

Casiple remarked that the political culture of the country has always been personalistic, often leaning towards an an identification with a strongman figure or a wise ruler exemplified by the Marcos dictatorship.

“Usually a strongman leader is sought when the community faces a threat or there is a desperation on an issue,” he stated.

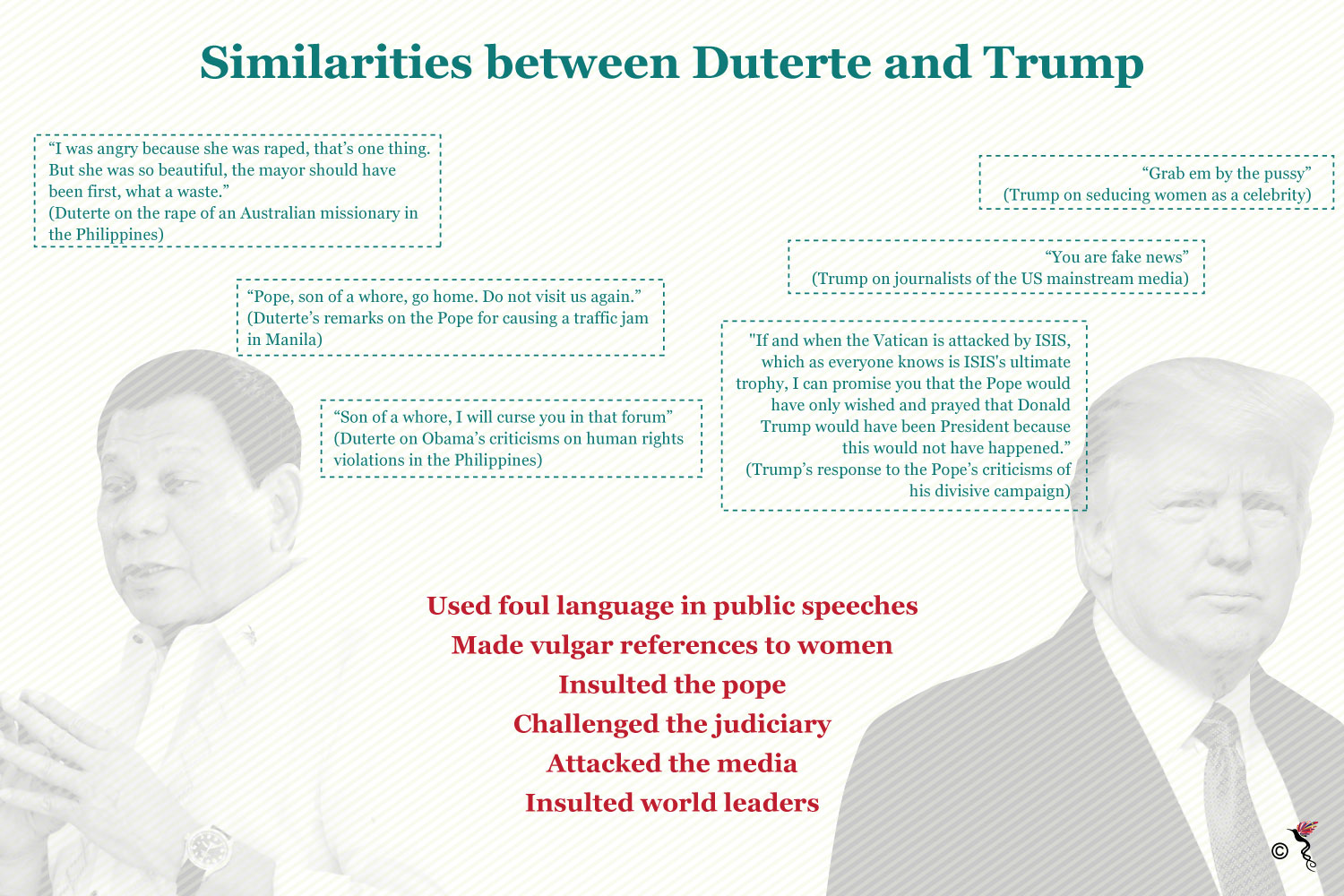

And that threat has for long, been drugs. Filipinos, sick of the political establishment’s lacklustre approach to crime fighting sought to elect an outsider from the status-quo as their saviour. That saviour came in the election of Duterte with his firebrand, unabashed leadership style earning him the moniker, “Trump of the East”.

Similarities between Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and US President Donald Trump.

He came in, all guns blazing and promised to wipe out crime by killing 100,000 criminals within the first six months of his tenure. His administration insists that Philippines is fast becoming a “narco-state” although data from the UN (United Nations) showed otherwise and within two months into office, he authorised shoot-to-kill orders against a list of criminal suspects which included a mayor and his son.

In a speech made last December, Duterte even admitted to personally killing criminals in the southern Philippine city of Davao during his nearly two decades as mayor there. At the time, he was infamously linked to the Davao Death Squad that embraced a vigilante style of justice which, according to Human Rights Watch, was responsible for the deaths of hundreds of petty drug dealers, street children and petty criminals since 1998.

Is it worth the falling crime rate?

The recent shootings of the teenagers have sent shockwaves throughout the nation and has called into question the efficacy of Duterte’s crime fighting strategy. De Guia believes that the better approach is one which rehabilitates drug offenders instead of putting an end to their lives, adding that “there must be proper dissemination on the evils of narcotics and better means of livelihood for poorer people so that they don’t have to resort to drugs to make ends meet”.

In response to the deaths, Duterte publicly apologised and relieved the entire police force in Caloocan – all 1,200 personnel. But he vowed never to stop this bloody war despite mounting criticism.

“With regard to the deaths, I’m sorry. But it had to happen,” he said in a speech in Davao City, adding, “I will fulfil my promises to the Filipinos. Just because there are some people who died there, and even teenagers, it doesn’t mean to say you have to stop.”

Does it really though, Mr President?