They're called "red zones" – COVID hotspots in Cambodia's capital of Phnom Penh that have gone into lockdown. But those living inside say food – and help – is scarce.

Somal Ratanak had spent nearly his whole pay cheque when his neighbourhood in Phnom Penh was locked down on 12 April.

The area was eventually designated a red zone – he was left unable to leave his house or go to work as a cashier.

Mr Somal is now unsure of where his next meal might come from.

He had earlier this month received a standard government issued aid package of rice, noodles, soy sauce, and canned fish.

But these deliveries are irregular and Mr Somal cannot count on them, saying he has to "eat a lot less than before".

He's not alone.

Harsh new restrictions aimed at controlling a late February outbreak have left tens of thousands trapped in their homes, with food insecurity a real problem.

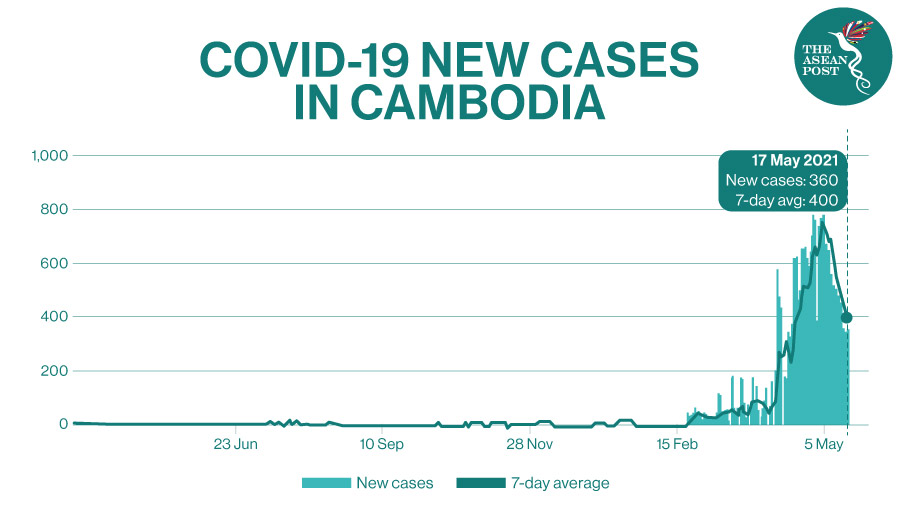

Despite Cambodia being lauded for its tight COVID-19 restrictions and relatively low case numbers last year, the country is now seeing around 400 new infections a day, and has over 20,000 cases and 150 deaths in total.

Hospitals are over capacity, forcing authorities to create temporary hospitals in stadiums and care centres, with some people in need of medical attention told to quarantine at home. As a means of containing the spread, the government has imposed progressively tighter restrictions on mobility, such as district lockdowns and colour-coded zoning.

Inside The Red Zone

There are an estimated 120,000 people living in Phnom Penh's red zones, according to the Center for Alliance of Labor and Human Rights (Central).

These red zones are COVID-19 hot spots, sealed off with barricades and strictly monitored by soldiers.

Phnom Penh currently has four such districts with individual sections still in lockdown, which will be retained until 19 May.

Residents in these zones are forced to remain in their homes under threat of arrest, fines or even violence, prompting aid organisations to express concern over human rights abuses. Rules and regulations vary from officer to officer and inconsistent disciplinary action has left residents without a clear understanding of what to do, with some able to leave for food runs and emergency healthcare and others trapped inside.

The Ministry of Commerce has sent buses doubling as mobile food shops in some neighbourhoods to make up for the mass closure of small shops and markets – but some can barely afford even this basic spread.

Residents living in these zones are seeing prices rise by as much as 20 percent and their income fall, said Central.

NGOs have also been barred from the red zones – making it even harder to reach those in need.

Amnesty International's Deputy Regional Director for Campaigns Ming Yu Hah says the government's response so far has been haphazard.

The government's aid package for example, have been sporadic – reaching only a fraction of those in the red zones.

These were initially advertised as 300,000-riel (US$75) relief payments, which could support a family's food intake for at least a couple of weeks.

Instead, the government decided to deliver groceries but critics say the packages are worth far less than the US$75 relief payments. More than 20,000 families have received the aid, according to the government, but the instances of individual need are still overwhelming.

"The government should ensure access to adequate and nutritious food, healthcare and basic social assistance for the most at-risk Cambodians during this critical time," said Human Rights Group, Licadho director Naly Pilorge.

Chhai Boramey, a casino dealer now trapped in a red zone, says her household is one which has yet to receive any government assistance.

"Three of our family members are jobless," Ms Boramey said of her eight-person household.

"We still have to pay full rent, electricity, and loans. We also cannot afford the increase in the price of food."

In late April, hundreds of residents in two locations of Stung Meanchey district – a red zone – began to protest against food shortages in their villages.

But these demonstrations were met with backlash and name-calling from local media and officials, as well as suggestions they were stunts spearheaded by the political opposition.

Amnesty International, as well as others serving in the non-profit sector, have received reports that residents speaking out over social media or through protests were warned that they could be denied aid, but the slow relief response has left them more famished than frightened.

"I also am afraid to speak out," Ms Boramey said. "But because I have no food, I have to protest." – BBC

Related Articles: