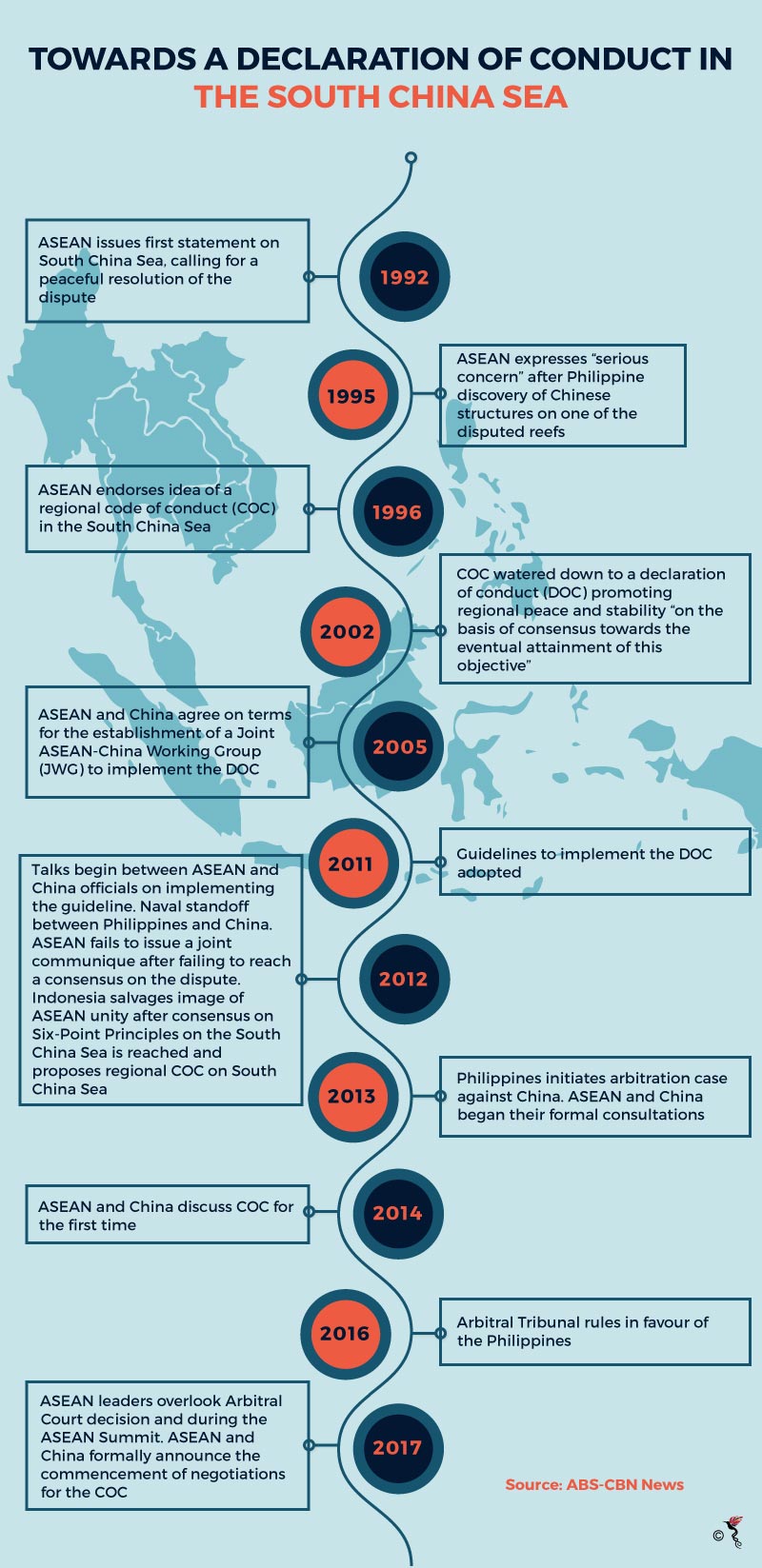

On the agenda for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) this year – as it has been for many years before – is the South China Sea dispute.

Singapore, as chairman of ASEAN will go into the year with the foundations towards dispute resolution seemingly made. Last November, China and ASEAN formally announced the start of negotiations for a Code of Conduct (COC) in the South China Sea. Months prior, Foreign Ministers adopted the COC framework during an ASEAN-China meeting.

From “declaration” to “code”

What makes the South China Sea a hotly contested body of water is its arterial role in regional trade and the abundance of hydrocarbon resources that is yet to be extracted.

So far, both ASEAN and China have clung on to a non-binding Declaration of Conduct (DOC) signed in 2002 which has been long overdue for change. However, the manner in which this change materialises, depends on the negotiations of the COC.

Right now, analysts can only infer the trajectory of subsequent diplomatic talks from the COC framework which was agreed upon in August last year.

In an analysis of the COC framework, Ian Storey, Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, suggests that the “…final COC may not look very different from the DOC.”

China, seems to view the COC as part of the process of implementing the DOC – not as a legally binding upgrade from the non-binding DOC. But ASEAN claimant states that want a more “comprehensive and effective COC” would have to bear with the protractions of international diplomacy as negotiations ensue – which can be incredibly frustrating.

Besides containing slightly stronger wording than the DOC, the COC includes references to the prevention and management of incidents – which was previously absent from the DOC. The framework also failed to mention or hint at any resource sharing agreements which would have set it apart from the DOC.

According to Senior Fellow at the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Malcolm Cook, a regional-level joint resource agreement is “very unlikely” as this fall under the concerns of individual states.

“Bilateral agreements between China and individual Southeast Asian claimant states are more likely. However, the fact that no such agreements currently exist suggest that even bilateral agreements are not likely,” he said, in reference to resource sharing agreements at a regional level.

Binding China

Analyst at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS) Malaysia, Thomas Daniel, holds that this is part of China’s “longstanding strategy of playing the long game in the South China Sea dispute.”

“Now that China has achieved significant gains with its ongoing reclamations and facilities building, frequent patrols by various agencies deep into the southern reaches of the South China Sea, and by all means managed to come though the tribunal ruling relatively unscathed – it can afford to offer a carrot to other claimant states,” he added.

“Make no mistake, progress on the COC has and will continue at a pace China dictates.”

Glimmers of China acceding to a legally binding deal were seen last November when Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte told reporters that “China has graciously agreed to a Code of Conduct and it binds itself to the agreement.” However, Duterte was referring to a bilateral deal between China and the Philippines and not between all claimant nation.

Daniel remarked to The ASEAN Post in an email response that the issue of a legally binding agreement is a fiddly matter – that it may sound good on paper but may lead to issues at a policy and implementation level.

“What I think will eventually happen with a COC is that to get all claimant states to sign up, it will be so watered down and perhaps even weak. I suspect that a COC that strongly prohibits claimant states in reinforcing their claims on the ground will not fly,” he opined.

Despite the diplomatic nitty gritty that comes with negotiating the DOC, this seems to be the best bet in brokering a long-term solution to the dispute. As negotiations are slated to take place this year, ASEAN’s resilience will be put to the test – whether the organisation comes out unscathed is anyone’s guess.

Recommended stories: