On 9 May, Malaysians from all walks of life exercised their right to vote and made history. For the first time in over 60 years, Malaysia will see a new ruling party in power.

Barisan Nasional – a coalition made up of various parties such as the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC) and Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) – and its predecessor the Alliance Party, have ruled Malaya and Malaysia since the nation’s independence in 1957. The results of the country’s 14th general election (GE14) saw the end of this long streak as an association of Opposition parties known as The Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan) led by former prime minister, Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad won the required number of seats to gain a simple majority in the Malaysian parliament to form its new government.

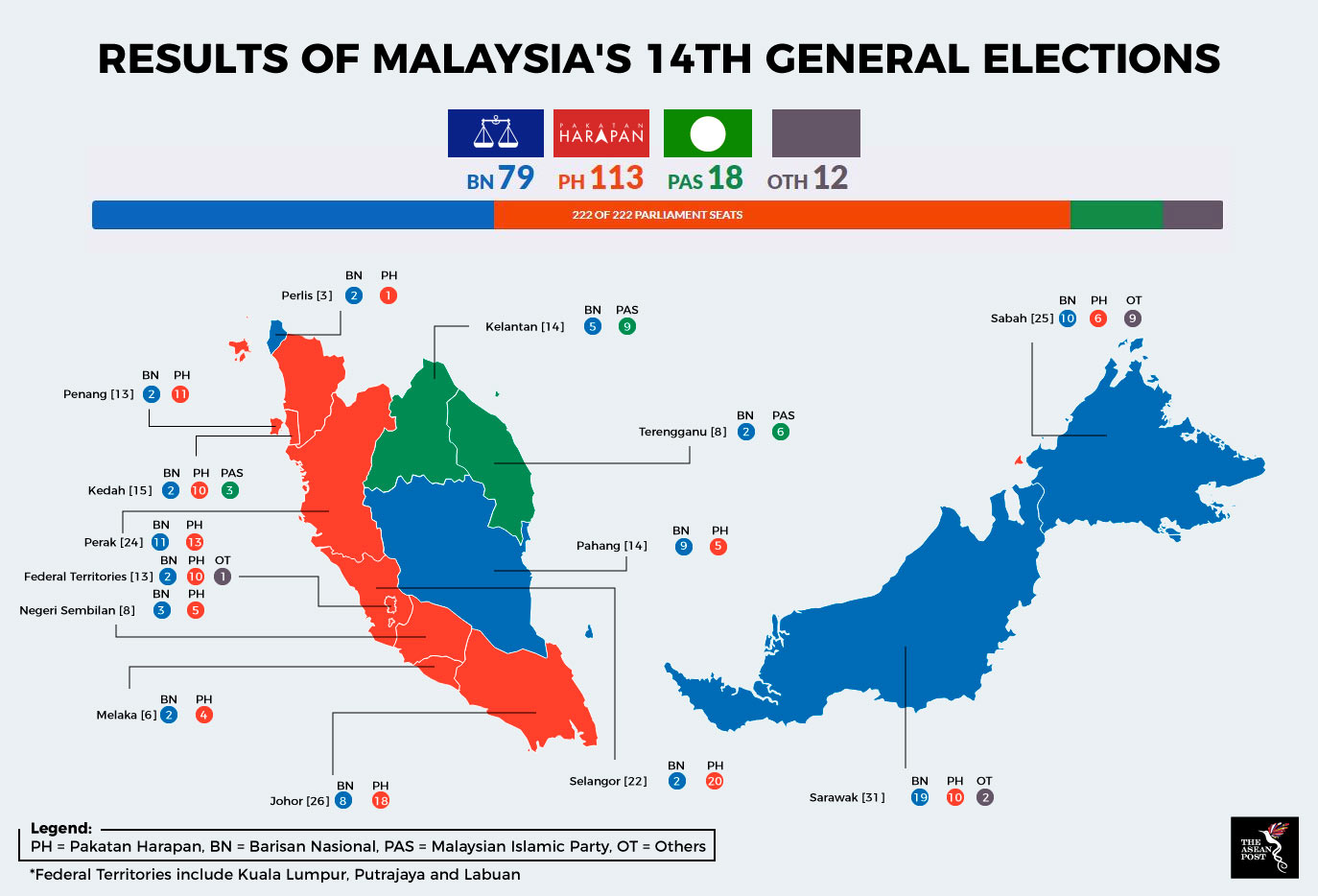

Pakatan Harapan’s political make-up consists of Dr Mahathir’s new party, Bersatu, the People’s Justice Party (Parti Keadilan Rakyat) or PKR, National Trust Party (Parti Amanah Negara) or Amanah and the Democratic Action Party or DAP. The Opposition coalition managed to secure 113 seats in GE14, while Barisan Nasional won a total of 79 seats.

Dubbed the “mother of all elections”, the run-up to the elections saw a dramatic and unlikely turn of events. Dr Mahathir had left UMNO – the party he once led – in 2016, going on to establish Bersatu later that year. In 2017, Bersatu agreed to join the Pakatan Harapan coalition to challenge the Barisan Nasional-led government, with Dr Mahathir agreeing to contest in the elections under the PKR flag. PKR was founded and led by his former political nemesis, Anwar Ibrahim, who is currently in jail awaiting a royal pardon.

The convoluted tale behind Pakatan Harapan’s genesis makes the results of GE14 all the more surprising. Prior to the election, many analysts had dismissed the coalition as a disorganised marriage of convenience, with surveys and studies projecting a hung parliament in the best-case scenario. In addition, the odds were already stacked against the Opposition, as Pakatan Harapan was up against a party with extensive financial backing and a firm grip on the mainstream media. Furthermore, allegations that Malaysia’s Election Commission was under the influence of the Barisan Nasional were rife.

Another surprise is the manner in which Barisan Nasional lost. The 79 seats it won in GE14 represent a 54-seat reduction from the 133 seats in the party took in 2013. While voter turnout was lower than that of the previous general election – which some speculate was due to in the polls being scheduled in the middle of the week – the message was clear: the people of Malaysia wanted change.

The Malaysian tsunami

When Dr Mahathir was named as the Pakatan Harapan chairman in 2017, the move drew criticism from loyalists in the coalition’s component parties. PKR and DAP in particular have had a history of troubled relationships with Dr Mahathir, as many of their members and activists were arrested and silenced under his previous administration, including Anwar Ibrahim, who was removed from political office and jailed. Leaders of these parties defended Dr Mahathir, however, calling his appointment a strategic one.

Dr Mahathir’s appointment as Pakatan Harapan chairman stemmed from the fact that he was the only political figure in Malaysia with enough influence to convert rural voters to the Opposition. In previous elections, Opposition parties had little trouble in securing support from urban demographics. However, they struggled to penetrate the rural heartland of Malaysia, which, prior to GE14, had been thought of as untouchable Barisan Nasional strongholds.

However, GE14 results show that Pakatan Harapan’s strategy has paid off. According to a survey by political think tank Invoke Malaysia during the run-up to the elections, Pakatan Harapan steadily gained popularity among ethnic Malays, while Malay support for Barisan Nasional eroded significantly.

The “Malay swing” towards Pakatan Harapan signifies a fundamental shift in Malaysian politics. Historically, parties such as DAP and PKR have been accused of propagating anti-Malay policies, leading to fears in some segments of the Malay community that Malay privileges would be abolished if Pakatan Harapan were to come into power. The Malay swing in GE14 shows that these fears have become less relevant and that the country is, perhaps, moving away from the race-based politics popularised in previous elections.

However, to credit Pakatan Harapan’s victory solely to a change of heart among ethnic Malay voters would be simplistic, with GE14 results in Sabah and Sarawak showing that Barisan Nasional’s defeat traces its roots to a larger “Malaysian swing” instead. These states, which have heretofore been Barisan Nasional holdouts, saw significant losses for the coalition. In Sarawak, DAP doubled their seat count from five to 12. Meanwhile in Sabah, newly formed Opposition party Warisan won eight seats, with Pakatan Harapan picking up six seats as well.

The Najib effect

Another factor that cannot be overlooked is the effect the alleged scandals of the Najib Razak administration had in drawing support for Pakatan Harapan. In 2015, then-prime minister Najib Razak was accused of embezzling US$681 million from 1MDB, a government-run strategic development company he was overseeing. Reports show that 1MDB has accumulated debts of nearly US$11 billion. While Najib Razak and his associates have strongly denied these allegations, there is no denying that these accusations, as well as his refusal to step down, have played a role in fostering public anger towards him.

During this period, there were calls from some quarters for his resignation and even arrest. Najib Razak responded to these allegations by shutting down any investigation set up against him. He also sacked the Attorney-General at the time, as well as four ministers who criticised him. However, each of these moves only served to further galvanise public anger towards him.

It’s difficult to quantify to what extent the discontent from these scandals translated into actual votes for Pakatan Harapan, but Barisan Nasional’s losses in areas that were traditionally safe seats is telling, with the party even suffering a major defeat in Johor – the birthplace of UMNO.

Ever since the results of the elections were announced, UMNO has been in alleged disarray, with rumours that party members are unhappy with the current leadership. While these concerns have likely been assuaged with Najib Razak’s 12 May resignation as Barisan Nasional chief, the question of UMNO’s future direction remains. With every news cycle, there are stories of UMNO members possibly defecting to Pakatan Harapan. Video footage of infighting in UMNO has also been recorded by members of the press, raising the possibility of the dissolution of UMNO in its current form, and perhaps an end for race-based parties in the country.

Economic growth – but for whom?

Najib Razak has always prided himself on the economic growth the country has seen under his watch. To his credit, the World Bank recently revised Malaysia's growth estimate four times in just a year. Institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have always projected a favourable economic outlook for the country, forecasting steady annual growth figures of between 5 to 6 percent.

However, despite the favourable economic outlook, frustrations among the people of Malaysia have grown steadily over rising costs of living and stagnating wages. This issue is particularly resonant among younger voters, who are facing challenges finding employment while having to cope with larger economic pressures as well. According to the nation’s central bank, youth unemployment is three times higher than the national average – 10 in every 100 youths are unemployed, compared to three in every 100 workers overall. Najib Razak’s failure to address such issues during his tenure were a factor in dwindling support among younger demographics, as local reports show that youths under 30 made up about 40 percent of the GE14 voter turnout.

What now?

On 10 May, Malaysians woke up to a new Malaysia - #MalaysiaBaru - as some might call it. The shift in mood is palpable, as people begin to realise that a whole new world of possibilities for the country has opened up.

With the institutional reforms promised by the Pakatan Harapan government, Malaysians will no longer be burdened by bureaucracy and archaic laws. One of the biggest reforms promised by Pakatan Harapan is the proposed abolishment of the Printing Press Act and Anti-Fake News Act. The abolishment of these acts will bring Malaysia one step closer to press and media freedom. Malaysian media outlets will no longer have to toe the government line and can finally carry out their duties with integrity and without fear.

Other institutional reforms include ensuring the independence of the judiciary, the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Agency (MACC) and the Attorney-General Chambers. Repressive laws such as the Sedition Act, Official Secrets Act, and Universities and University Colleges Act (UUCA), among others, are also expected to be abolished. If the Pakatan Harapan government manages to follow through with these promises, then #MalaysiaBaru will become a reality.

As Dr Mahathir now becomes the seventh prime minister of Malaysia, there are some concerns being raised over his manner of rule. During his time in power, Dr Mahathir was nothing short of controversial. As Prime Minister, he arrested dissidents who questioned his policies, he pushed for Malay-centric policies which have ruined race-relations until today, and he sacked his deputy, Anwar Ibrahim and sent him to jail, among many other incidents. Some quarters attribute many of Malaysia’s deep-rooted sociopolitical issues to his previous administration. As such, the question of whether he can truly end corruption in Malaysia is a valid one.

While there is no way to answer these questions without speculation, what is certain is that Dr Mahathir is now surrounded by politicians such as Lim Guan Eng, Nurul Izzah, Rafizi Ramli, Azmin Ali and others, who have spent their entire lives fighting for institutional reform. With these figures likely to form part of Malaysia’s future Cabinet, it is unlikely that Dr Mahathir will be able to exert the same level of control as he did in his previous administration.

In the event that he should try, Malaysians newly emboldened by their demonstration of voting power in GE14 will likely stage an encore during the next election. Pakatan Harapan has to realise that Malaysians have never been more aware of the power they possess in shaping the future of their country. After all, it was ordinary voting Malaysians who led this peaceful revolution and it will be them who get to decide when another one is required.