A recent report that Malaysia is the world’s second-largest importer of shark fin should come as no surprise judging by the government’s seemingly indifferent attitude towards shark conservation.

Appetite for shark fin soup has seen populations of some species crash by over 90 percent in recent years, and Malaysia is playing a large role in that decline with its imports of shark fin – which are now ahead of China.

Sharks can be consumed in Malaysia because they are listed as ‘fish’ under Malaysia’s Fisheries Act, leading to calls for a total ban on shark fishing as it is being carried out at an unsustainable level.

Shark fin is one of the most expensive seafood items in the world, and demand for shark fin soup – seen as a delicacy in parts of Asia – is leading to the entire species being overfished. Around 100 million sharks are fished every year, mostly for their valuable fins which can cost up to US$400 per kilogram.

More than half of shark species and their relatives are categorised as threatened or near-threatened with extinction according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Shark Specialist Group, with 17 of 58 species evaluated in March classified as facing extinction – all the more disheartening since sharks have stalked oceans for 450 million years and have outlasted dinosaurs.

All these facts do not seem to matter for Malaysians.

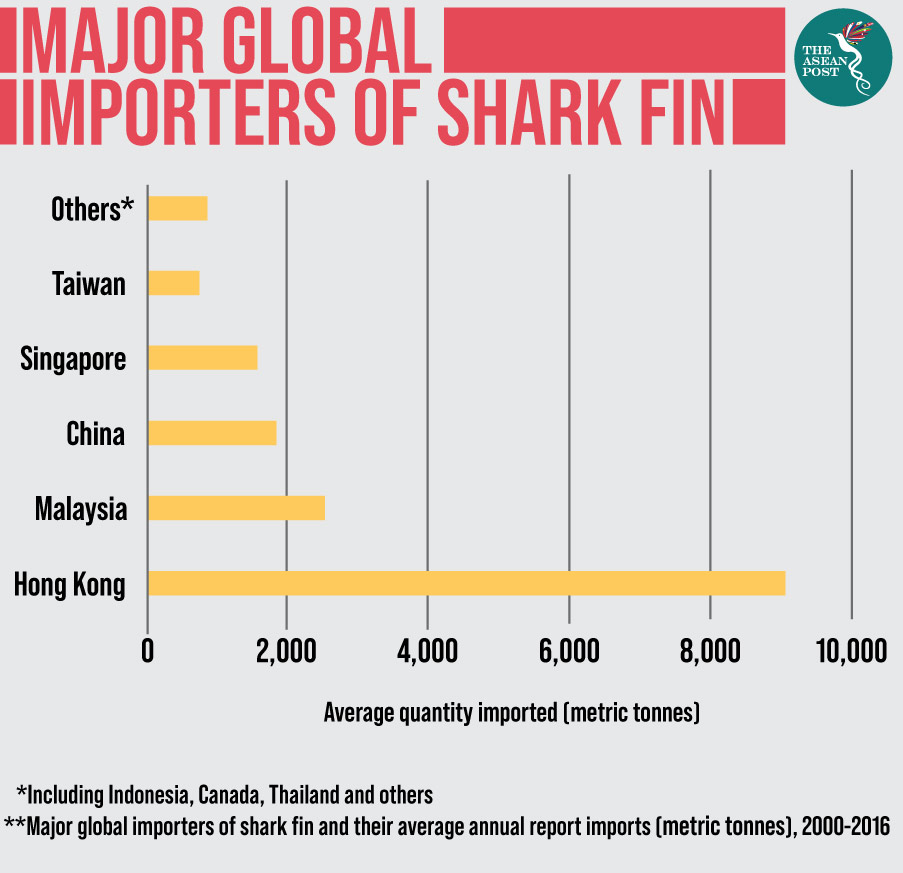

They imported an average of 2,556 tonnes of shark fin per year between 2000 and 2016 according to wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC in a report released earlier this month, with Hong Kong topping the table with an average of 9,069 tonnes. China and Singapore were third and fourth with 1,868 tonnes and 1,587 tonnes respectively.

These four largest importers accounted for 90 percent of average annual global imports of shark fin during the same period. The 2017 edition of the TRAFFIC report ranked Malaysia third behind Hong Kong and China.

Malaysia snubs CITES proposal

This year’s TRAFFIC report was released just weeks after Malaysia – as with most other ASEAN countries – voted against a proposal tabled at a Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) meeting to impose rules on the sustainable trade of 18 species of sharks and rays.

Represented by the Ministry of Water, Land and Natural Resources, Malaysia voted against the proposal as it argued that the species listed in the proposal were actually by-catch and their population “will not be affected by exploitation and trade of those species,” according to the Fisheries Department.

“Whether a by-catch or a targeted species, few controls are in place to limit harvest levels … and it is unclear whether the current levels of extraction are sustainable for all or certain shark species,” Meenakshi Raman, president of environmental NGO Sahabat Alam Malaysia (Friends of the Earth Malaysia) was quoted as saying to local media.

“The fate of the world’s sharks is in the hands of the top 20 shark catchers, Malaysia included, many of whom have failed to demonstrate what they are doing to save these imperilled species,” she added.

Calling for a total ban on shark fishing, Raman said that losing more sharks and rays would have unintended consequences since they are top ocean predators and help to balance marine ecosystems.

Shark finning

Served at weddings, celebrations and cultural holidays, shark fin soup has been associated with a variety of dubious medicinal benefits which have not been scientifically proven.

The fin, however, is of little nutritional value – with most of the soup’s flavour coming from the broth.

Once a deep-rooted status symbol on dining tables across the region, shark fin soup has lost most of its lustre amid concerns of overfishing and the revulsion over the cruel way in which the fins are harvested – also known as shark finning.

Shark finning is the practice of removing all of the shark’s fins – up to eight of them – after they have been caught. As its meat can be 250 times lesser in value than its fins, sharks are then usually dumped back into the ocean to save space on fishing vessels for more prized catch. Unable to swim or pass water through its gills to absorb oxygen, these sharks are left to die an agonising death – and its meat, a valuable source of protein, goes to waste.

One of the most talked about incidents of shark finning in Malaysia happened in 2016 when photos of nearly a dozen sharks left to bleed to their death in the famed dive haven of Mabul island in the eastern state of Sabah were widely circulated on social media to the horror of tourists and locals alike.

While the state minister in charge of environment, Masidi Manjun, condemned the photos, he admitted there was little he could do as there was no law banning the practice.

“The photos speak volumes of what I and many other Sabahans have been advocating for the last five years. What difference does it make when there is no law against this despicable act?” he was quoted as saying.

It looks like little has changed since then.

Related articles: