In the aftermath of a watershed election in Malaysia last May, newly minted Prime Minister, Dr Mahathir Mohamed set about fulfilling his reform pledge which catapulted him back into office for a second term. Having ousted one of the longest ruling political parties in the world – the National Front (Barisan Nasional) which governed Malaysia for over 60 years – Dr Mahathir has with him a team with very little governing experience at the federal level who have yet to shed their siege mindset of being in the opposition.

To negate this conundrum, Dr Mahathir formed a five-person Council of Eminent Persons (CEP) led by Daim Zainuddin. Daim is himself a controversial and illuminating figure of the past, having served as former Finance Minister during Dr Mahathir’s previous tenure as Prime Minister. The council is primarily tasked with advising the cabinet on policy related matters, implementing the newly elected Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan) coalition’s election promises and reviewing the country’s existing or proposed mega-projects and international business deals.

However, a recent spate of reports suggests that many leaders within the new government as well as the general public are growing uneasy over the council’s shadowy actions that seem to overstep the boundaries of its advisory role.

An advisory role

At the heart of this issue is the vague and ill-defined advisory role under which the council operates. Malaysia practices a flawed form of separation between the three branches of government (i.e. executive, legislative and judiciary) where power is very much concentrated in the hands of the executive and the Prime Minister – a legacy remnant of Dr Mahathir’s first term in office. Hence, the role of the CEP as advisor to the executive has cast doubts in many that the council serves as a higher power to the cabinet.

To begin with, the CEP is neither a creation of statute nor is it a body of enquiry under Malaysia’s Commissions of Enquiry Act 1950. Besides that, it wasn’t formed by way of a parliamentary vote, nor does it function as a select committee which is answerable to the country’s lawmakers.

This is very much reminiscent of China’s politburo structure where power is centralised within the hands of a small group of individuals. There is also the added furore to the council’s actions given that its five members are unelected by the people and are seemingly not held accountable to the country’s set of checks and balances.

Dr Mahathir’s cabinet, however, is insistent that they are not being arm-twisted by the CEP and act independently. However, glaring gaps in the government’s explanation of the CEP’s role must be addressed – mainly concerning the boundaries within which the council should operate.

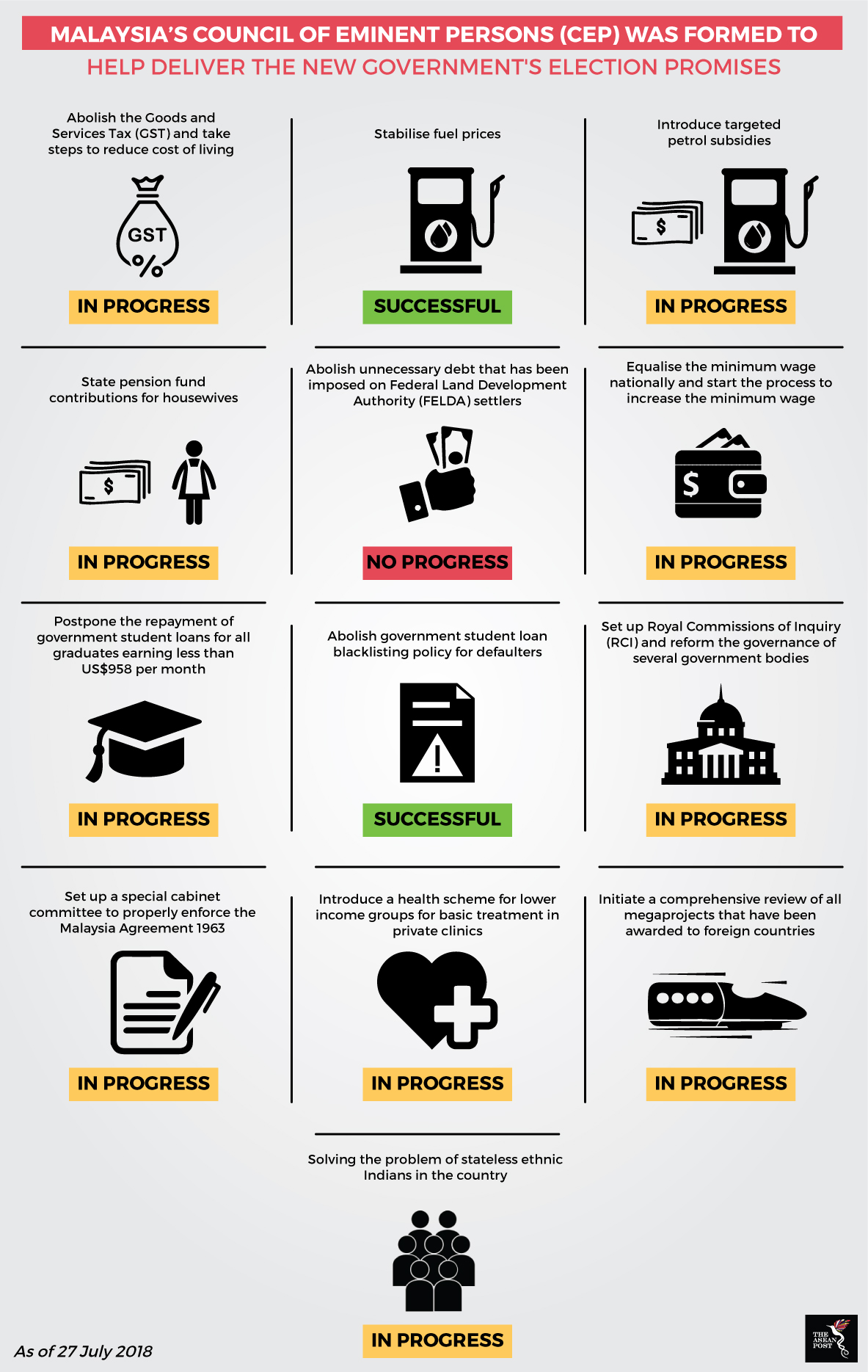

Source: Various sources

Among the top priorities on the CEP’s to-do-list is the cull and restructuring of government institutions and state-owned enterprises. Since Dr Mahathir’s historic victory in the May polls, the country has seen a spate of resignations by top government and corporate leaders.

While the CEP is not responsible for every departure, they have been linked to the resignation of several top leaders including the governor of the Central Bank, the Chief Justice, and the President of the Court of Appeals. In the case of the latter two, the CEP had summoned them to a meeting where council member, Daim effectively sought their resignation.

Daim has also come under fire for representing the country on a diplomatic mission to China recently where he met with Premier Li Keqiang while not holding any formal position within Malaysia’s federal government.

According to Mustafa Izzuddin, Fellow at the Singapore based ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, the point of contention with Daim’s visit to China hinges on whether Malaysia’s Foreign Ministry was kept in the loop of the CEP’s actions. He says that because the CEP was created before the new government had appointed a Foreign Minister.

“Moving forward, I expect the council and the Foreign Ministry to act in a more cohesive manner,” he said, thus suggesting that, there should be clear lines of communication and transparency in action.

“The CEP may not necessarily be bound by government protocol because they play an informal role. But, it is still an influential role, hence they must be sure to keep the relevant ministries informed of their actions,” he further reiterated.

Sending the right message to the market

The CEP’s actions have nevertheless led to significant pushback by government backbenchers as well as opposition members as to whether some of the actions of the council were signs of political overreach. Moreover, they point to a blatant disregard of Dr Mahathir’s campaign commitment to initiate institutional reforms and to raise the standards of democracy in the country.

When initiating the council, Dr Mahathir insisted that the CEP would cease to exist after 100 days – in reference to the duration of which his coalition intended to fulfil several of its key pledges. However, Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah was reported by local media in the country as saying that there is no guarantee the council will be disbanded as promised given recent criticism by opposition members of parliament on deliverability of those pledges. With the CEP seemingly looming over the heads of ministers indefinitely, questions are expected to be raised with regard to whether they could fulfil their duties independently

Speculation was also rife – as was reported by Singapore’s Straits Times – that the council requested the top management of Khazanah Nasional, Malaysia’s strategic investment arm to resign. Days later, the board members of the entity handed their undated resignation letters en bloc.

Cassey Lee, Senior Fellow at Singapore’s ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, opined that this was a good move by the board of Khazanah Nasional.

“The fact that the letters were undated shows that the board has given the government an option as to whether they would like to retain or dismiss certain members,” he said, adding that such restructuring exercises were not without precedent in Malaysia.

The resignations come amid criticisms by Dr Mahathir that Khazanah Nasional deviated from its original purpose of helping the ethnic Malay Bumiputera population. In response, former premier, Najib Razak stated that the entity’s purpose was not to enrich just the Malay population but for a wider purpose of nation building, irrespective of race.

Lee pointed out that in wanting to pursue this “original purpose,” the government is looking at the arm’s restructuring from a long-term perspective.

Lee further added that because the government would have full liberty to pick the next cohort of board members, it would have to be more accountable for Khazanah Nasional’s actions.

“It’s now a clean slate. The government can’t turn its back and say in five years that they couldn’t do what they intended to,” he said.

The selection of future board members will undoubtedly be closely monitored by local and foreign investors alike. It is likely that Dr Mahathir’s picks could result in further changes to the management team at Khazanah Nasional. This could create an air of uncertainty amongst fund managers who are investors in companies that Khazanah Nasional has major stakes in.

Additionally, there is further speculation that Khazanah Nasional would be joined by state oil firm, Petroliam Nasional (PETRONAS) and the state’s strategic fund manager, Permodalan Nasional Berhad (PNB) under the Prime Minister’s Department. The sub-department which itself is under the purview of the Prime Minister signals a return to Dr Mahathir’s political culture of centralised leadership which is seen by many as the primary cause of the rot in Malaysia.

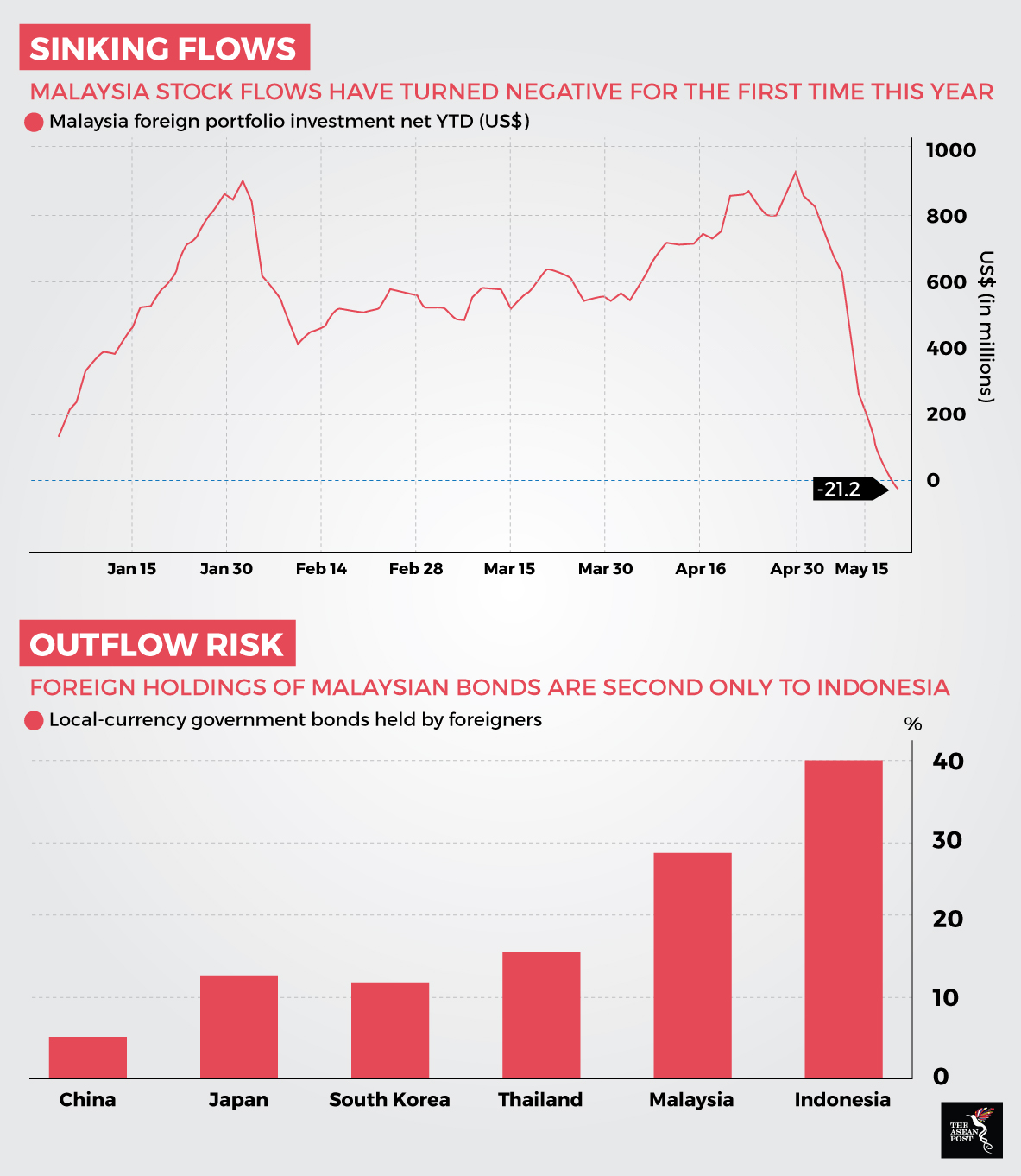

Within a week of the elections, Bloomberg reported that US$937.8 million of foreign inflows into Malaysia’s stock market had been wiped out. For the first time in 2018, Malaysia’s stock flow turned negative as foreign investors remained uncertain over the new government’s economic plans. While recent trends indicate net foreign selling in the equities market is dissipating, the market is yet to fully recover to high levels prior to the general elections.

Moreover, the recent interest rate hike by the Federal Reserve (Fed) in the United States (US) has seen emerging economies like Malaysia’s take a beating with the local currency weakening, due to the strengthening US dollar. The popularity of Malaysia’s local currency denominated sovereign bonds held by foreign investors could also decline in the long term unless more proactive measures are taken to restore foreign investor confidence.

Source: Bloomberg

As of end-2017, foreign holdings of Malaysian bonds were second only to Indonesia in the region, at 29 percent according to the Asian Development Bank (ADB). However, regional analysts have indicated that post-elections, foreign holdings of such bonds have since deteriorated. There have been signs that a chunk of the outflows is making its way to other financial capitals in the region because of the relative political stability there.

For investors in emerging markets, a prime concern is political stability which can only exist if a government remains unfaltering. The actions of the CEP of late, seem to undermine the integrity of the executive branch of government and may send a wrong signal to fund managers and retail investors alike.

The euphoria of the Alliance of Hope’s unexpected win in the general election has yet to die off – giving Dr Mahathir’s CEP ample political leeway to possibly skirt democratic principles in the name of the greater good. In the era of a “new Malaysia” where a culture of free speech and rule of law has emerged, the citizens of the country should stay vigilant and pressure those within the corridors of power to hold the CEP accountable for their actions, or the country could slide back into its questionable ways of the past.

Currently, Malaysia’s new government has less than three weeks to honour its 100-day pledge, failing which, they could be possibly flayed in the court of public opinion or more likely by hawkish opposition members waiting for an opportunity to pounce. With most of its election promises not yet fulfilled, this begs an important question – has the CEP been effective in executing its role? Will Malaysia be a model for democracy in the region?